Algeria terror leader preferred money to death

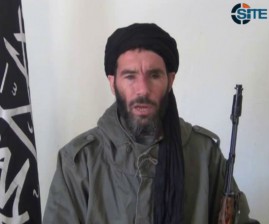

BAMAKO, Mali— Moktar Belmoktar is known abroad as the man who orchestrated the abduction of scores of foreigners last week at a BP-operated plant in the remote, eastern corner of Algeria, in a raid that led to many of their deaths.

In the Sahara at least up until this week he was, ironically, known as the more pragmatic and less brutal of the commanders of an increasingly successful offshoot of al-Qaida. The question now is has he evolved into an international terrorist every bit as violent as his rivals, or did the Algeria operation go very differently than he intended?

Belmoktar, an Algerian in his 40s known in Pentagon circles as “MBM,” just split off from al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, to start his own franchise.

Over the past decade, AQIM has kidnapped dozens of foreigners, including diplomats, aid workers, field doctors and tourists. Although Belmoktar’s hostages are forced to endure months of privation and live with the constant threat of execution, those who have dealt directly with him say his cell has never executed a captive, according to hostage negotiators, a courier sent to collect proof-of-life videos, senior diplomats and security experts interviewed for this article.

The notable exception was the 2011 kidnapping of two French nationals from a bar in the capital of Niger, both of whom were killed when the French military tried to rescue them. It’s unclear if the two died from friendly fire, or were executed by their captors in a situation that closely mirrors the chain of events in Algeria, where combat helicopters strafed the compound in an effort to liberate the hostages, killing both kidnappers and victims.

Article continues after this advertisementBelmoktar prefers to trade his hostages for money, experts have said, and global intelligence unit Stratfor says he can get an estimated $3 million per European captive. The money allowed him to build one of the best-financed cells of al-Qaida. It may explain how he was able to strike out on his own six weeks ago to create “The Masked Brigade,” whose inaugural attack was launched inside Algeria.

Article continues after this advertisement“MBM is more along the lines of, how do I negotiate and put extra money in my pocket?” says Rudolph Atallah, the former head of counterterrorism for Africa at the Pentagon, who has spent years tracking the terror network in this Sahelian country. “The others are purists.”

Belmoktar is a contrast to his more ruthless colleague, Abou Zeid, who beheaded a British national and executed a 78-year-old Frenchman in 2010 in retaliation for a raid attempting to save him that killed six militants.

Up until December of last year, both men were emirs of their own “katiba,” or brigade, in AQIM. Though they are both from southern Algeria, they have chosen to embed themselves in northern Mali, in the immense, ungoverned desert which ranges from feather-soft dunes to flat, rocky plains. And both have made tens of millions of dollars by kidnapping French, Canadian, Spanish, Swiss, German, English and Italian nationals.

The contrast between the two is captured in the recently published memoir of Robert Fowler, a Canadian diplomat who was kidnapped by Belmoktar in 2008 in Niger, where he had been sent as a United Nations special envoy. Fowler was tied up and shoved into a pickup truck and the blows he suffered as his body was banged against the metal during the multi-day journey to Mali caused a compression fracture in a vertebra.

Fowler’s ordeal could have been much worse. He described how on April 21, 2008, the day he was liberated, he was driven to a rendezvous point. The same day, Abou Zeid’s troops arrived with two women, one of them on the point of death.

Belmoktar went to inspect the women, and returned to where Fowler was sitting with a “thunderous look on his face,” he wrote in his account “A Season in Hell.” Belmoktar asked to be passed dysentery pills from the medical kit, and ran back to give them to 77-year-old Marianne Petzold, a retired German teacher, and Swiss national Gabriella Burco Greiner.

When Fowler saw the two “the shock was physical. I recoiled with horror at the sight of those small, troubled white faces, twisted with pain.”

One had been bitten by a scorpion, and her arm had ballooned and turned black. She would later spend six weeks in the hospital getting skin grafts to replace the necrotized flesh, he writes in “A Season in Hell.” They both suffered from dysentery, and Abou Zeid had refused to give them the medicine that their governments had sent during their negotiation. At the moment that they were supposed to be released, Abou Zeid decided that he was not ready to free them, and an argument ensued between him and Belmoktar.

The same man who masterminded the recent horror in Algeria last week was visibly disturbed, wrote Fowler. He said it was Belmoktar who intervened, overruling Abou Zeid to free the two, ordering the drivers to take off across the trackless desert.

“If you are kidnapped by Belmoktar you would most likely live — and you could not say the same thing for Abou Zeid: All the hostages killed between 2006 and 2012 were killed by Abou Zeid. You don’t want to be in a position of describing him as the ‘noble savage.’ But I do think his thought process is less distorted by ideology,” says Geoff Porter, founder of North Africa Risk Consulting, a political risk firm specializing in the Sahara region, who has tracked Belmoktar for years. ”

However, long before this week’s attack in Algeria, Belmoktar had also shown brutality. His men attacked a military base in Mauritania in 2005, killing over a dozen soldiers, said Dakar, Senegal-based analyst Andrew Lebovitch. And he’s twice been sentenced to death in absentia in Algeria for the killing of customs officials and border guards, according to Abdel Bari Atwan’s upcoming book “After Bin Laden.”

His trajectory up until last week was nearly identical to that of Abou Zeid. Like Abou Zeid, he joined the Armed Islamic Group, or GIA, an Algerian extremist organization which arose in the aftermath of the 1991 election, which was voided by the secular government after an Islamic party won. He then joined the GIA’s offshoot, the GSPC, a group that carried out suicide bombings against Algerian government targets. In 2006, when the group became part of al-Qaida, changing its name to al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, both Abou Zeid and Belmoktar became the head of individual brigades.

Belmoktar claims he trained in Afghanistan in the 1990s, including in one of Osama Bin Laden’s camps. It was there that he reportedly lost an eye, earning him the nickname “Laaouar,” Arabic for ‘One-eyed.’ Research by the Washington-based Jamestown Foundation claims Belmoktar became the conduit between the core al-Qaida and AQIM.

But early on, there were signs that Belmoktar was not in step with the gratuitous violence that characterized both the GIA and the GSPC, as well as AQIM. A diplomatic cable from the U.S. Embassy in Algiers quotes Algerian sources who say that at different times, Belmoktar denounced both GIA and AQIM tactics because they caused many civilian casualties.

Last December, after rumors of a growing rift with Abou Zeid, Belmoktar announced that he was leaving AQIM and creating his own group, “The Masked Brigade.” His close associate, Oumar Ould Hamaha, told the AP that Belmoktar wanted to create a pan-Saharan movement, and the North African chapter was too narrowly focused on countries in the Maghreb, or North Africa.

It came as the United Nations was getting ready to authorize a military intervention to take back Mali’s north from Islamic extremists, including Belmoktar’s group. When France began airstrikes on Jan. 11, destroying a training camp, several weapons depots and a base known to be used by Belmoktar’s men in the northern Malian town of Gao, Hamaha raged that now their jihad would go “global.”

It was only a few days later in the tiny town of Ain Amenas in far eastern Algeria that turbaned men claiming allegiance to Belmoktar descended on a natural gas complex, operated in partnership with BP and took hundreds of hostages in the most ambitious terrorist operation the North Africa had ever seen. They forced the hostages to wear explosives. Belmoktar issued a statement saying the dozens of captives would be killed if France didn’t halt its military incursion in Mali.

No one will ever know what would have happened if Algeria or other governments agreed to negotiate. Instead, the Algerians sent in helicopters, pounding the compound, and in the bloodbath that ensued, at least 32 militants and 23 captives were killed, according to the Algerian government. It’s unclear how many were killed by friendly fire, and how many were executed by Belmoktar’s men.

One of the people that knows him best says these events in Algeria signal that Belmoktar has chosen to walk down the path of Abou Zeid.

Moustapha Chaffi has been the main hostage negotiator on many of the kidnappings carried out by both Belmoktar and Abou Zeid. It was he who was waiting to receive Fowler and the two women on April 21, 2008. He confirmed that Belmoktar ran to give them the dysentry pills, and later insisted they be released.

“Before he led this operation in Algeria, that was the sentiment I had, that Belmoktar was less brutal,” Chaffi said by telephone on Friday. “Now I find myself thinking that they are all terrorists. That they all take hostages. That they are all fanatics. So to draw a difference between them is really, really relative. There’s in fact no difference anymore.”

__

Associated Press writer Jamey Keaten in Dakar, Senegal and Cassandra Vinograd in London contributed to this report.