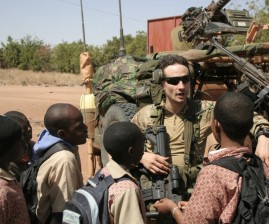

A French soldier talks with young residents of San in central Mali, as French troops pass through en route to Sevare, Mali, Friday, Jan. 18, 2013. French forces encircled a key Malian town on Friday to stop radical Islamists from striking closer to the capital, a French official said. The move to surround Diabaly came as French and Malian authorities said they had retaken Konna, the central city whose capture prompted the French military intervention last week. AP Photo/Harouna Traore

DAKAR, Senegal — West African nations that promised to send troops to fight al-Qaida in Mali are finding it’s a lot trickier than they’d hoped to actually get boots on the ground.

Political debates, fears that fleeing militants might scatter abroad, and logistics — even feeding the troops— have stalled plans to deploy against the nimble jihadists in Mali.

Saturday’s summit of West African regional bloc ECOWAS in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, aims to flesh out plans for ramping up its military role alongside the French soldiers now leading the combat.

“Our troops haven’t left yet because we have to make sure we assemble everything they need to survive over there,” said Defense Minister Abdoul Kabele Camara of Guinea, which has promised 144 troops. “Food, vehicles … our soldiers need to eat and care for themselves once they’re on the front.”

France’s unilateral move to intervene in Mali has forced both European and African contributors to a long-planned, U.N.-backed stabilization effort for Mali on a faster track. Europe is offering to help train Mali’s feeble army, but wants to leave African forces to the front-line role.

“The picture we have of the military operations in Mali enables us to appreciate the seriousness of the developments under way,” Charles Koffi Diby, Ivory Coast’s foreign affairs minister and chair of the ECOWAS mediation and security council, said Friday. It “also leads us to face up to the weight of our responsibilities in conducting and coordinating military operations in Mali.”

The African mission has three goals: to free Mali’s vast north from the clutches of Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Islamist allies MUJAO and Ansar Dine; stabilize Mali so that elections can be organized; and eradicate the terror menace in the arid Sahel region along the south Sahara.

The first African troops began trickling into Mali on Thursday with about 250 total soldiers from Togo and regional powerhouse Nigeria — nearly a week after France launched air strikes.

At full strength, the African deployment is to reach some 3,000 troops, including four battalions of 500 men each from Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria and Togo, French military spokesman Col. Thierry Burkhard said Friday. Critics say that’s far too few to stabilize Texas-sized northeast Mali.

At Saturday’s meeting, the big issue will be sorting out a central command for the African force, a French official said on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to publicly discuss the sensitive security matters. Nigerian Gen. Shehu Usman Abdulkadir is expected to be named the force commander.

The north-central African country of Chad — which is French-speaking like much of western Africa, but not in ECOWAS — this week committed to sending as many as 2,000 troops. Chad’s contribution was seen as especially important because its troops are familiar with arid, desert terrain like that in north Mali.

“We expect to send an infantry regiment and two support battalions,” said Foreign Minister Moussa Faki Mahamat. So far, about 150 Chadian troops have been stationed in Niamey, Niger, according to Burkhard.

ECOWAS started talking last year about sending a force to Mali initially to support that country’s poorly equipped army, amid the threat from jihadists who have controlled northeast Mali for nine months after capitalizing on chaos from a coup d’etat in the capital, Bamako, in March.

Another question is: Who pays? The U.S. will finance a big part of the African operation, the French diplomatic official said, as will European Union countries, relieving Africans of any possible financial pressure. This will be discussed at a donors’ conference in Ethiopia’s capital on Jan. 29.

France’s step on the accelerator has put an uncomfortable spotlight on the Africans, who previously hadn’t been expected to deploy in full before September. Speaking to The Associated Press this week, Col. M’Bawine Atitande, a military spokesman in Ghana, said: “We have not fixed a date yet on when the troops will move. We would let you know when we decide on a date.” He declined further comment.

Analysts say the public in western Africa generally supports the intervention in Mali, but fear potential fallout.

“They fear their borders are so porous and they know that some of these fighters come from their countries, so there are fears that they will come back home and try to set up cells,” said Nadia Nata, a political governance officer at the Open Society Initiative for West Africa in Dakar.

French officials, acting on a call for help from Mali’s president, say they felt compelled to go in first after Islamist extremists seized the town of Konna along a narrow belt separating north and south Mali, menacing the feeble central government in Bamako. French officials fear the region, if left to fester, could become a launching pad for terrorism against Europe.

Valentina Soria, a security analyst with London-based IHS Jane’s, said she believes West Africans have the political will to deploy a force in Mali, but questioned how effective it would be. She said with every day that passes the possibility of an ECOWAS force leading in Mali becomes less feasible — with France continuing to ramp up its presence and Chad forces headed in.

“They have shown they are willing to do it, but in terms of usefulness of forces in this first initial stage, I’m very doubtful about their ability to make a difference,” Soria said of the West Africans. Nigeria is the only nation in the region with experience in combat and fighting terrorism, she said.

Senegal “has not come out as assertively,” Soria said. Some political opposition leaders insist Senegal cannot send troops to war without the authorization of parliament, even though President Macky Sall has promised 500 troops; none has yet been deployed. The parliament in Mali’s eastern neighbor Niger, which has been hit by hostage-takings by jihadists, took up a debate on that deployment this week. It, too, has pledged 500 soldiers.

For a continent with relatively little experience in projecting power abroad, a quick African deployment was hardly certain. Even France, a former colonial ruler in Africa and one of Europe’s top military powers, has needed some logistical help from European allies to get troops into Mali.

Germany was deploying two C-160 military transport planes that will remain on standby in Senegal starting Sunday, awaiting orders to eventually ferry African troops into Mali.

Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb operates not just in Mali, but also in a corridor along much of the northern Sahel. This 7,000-kilometer (4,300-mile) long ribbon of land runs across the widest part of Africa, and includes sections of Mauritania, Niger, Algeria, Libya, Burkina Faso and Chad.

Johnnie Carson, the top U.S. diplomat for Africa, said Wednesday in Washington that the rebellion in Mali “constitutes not just a threat against a sovereign state, but potentially a transnational threat that could move into Niger, into Burkina Faso, into Mauritania, into Senegal, as well as Algeria and other places … So it is important. We cannot in fact take it lightly.”

That same day, militants said to be linked to Mali’s rebels took scores of people hostage — many of them Westerners — at a natural gas plant in remote eastern Algeria, launching deadly clashes and a standoff with Algerian forces that remained unresolved late Friday.

___

Michelle Faul in Johannesburg, South Africa; Boubacar Diallo in Conakry, Guinea; Robbie Corey-Boulet in Abidjan, Ivory Coast; Francis Kokutse in Accra, Ghana; Dany Padire in N’Djamena, Chad; Sadibou Marone in Dakar, Senegal; Juergen Baetz in Berlin; Greg Keller and Angela Charlton in Paris; and Bradley Klapper in Washington contributed to this report.