Turkey lifts ban on thousands of books

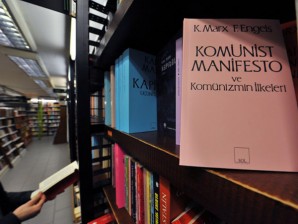

The Communist Manifesto, a publication written by the political theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels is pictured in a bookstore on January 5, 2012, in Istanbul. Thousands of books banned for the past few years returned to the shelves in Turkey, on January 5, 2013. AFP /BULENT KILIC

From communist works to a comic book, thousands of titles banned by Turkey over the decades were taken off the restricted list Saturday, thanks to a government reform.

In July, the parliament adopted a bill stipulating that any decision taken before 2012 to block the sale and distribution of published work would be voided if no court chose to confirm the ruling within six months.

The deadline came and went Saturday and no such judicial decisions were recorded, the head of Turkey’s TYB publisher’s union, Metin Celal Zeynioglu, told AFP.

“All bans ordered by (the courts in the capital) Ankara will be lifted on January 5,” city prosecutor Kursat Kayral confirmed to AFP.

Kayral had announced last month that he would let lapse every ban in his jurisdiction, a decision that cleared 453 books and 645 periodicals in that area alone.

Article continues after this advertisementAmong them were several communist works such as the “Communist Manifesto” written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, as well as writings by Soviet tyrant Joseph Stalin and Russia’s revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin.

Article continues after this advertisementOthers included a comic book, an atlas, a report on the state of human rights in Turkey and an essay on the Kurds.

But the books under Kayral’s jurisdiction make up only a fraction of all the titles affected—a total of up to 23,000 works according to Zeynioglu, who said he learned the number from the justice ministry.

The ministry did not immediately confirm the total—a number that Zeynioglu added was hard to nail down.

“These bans weren’t implemented in a centralised fashion: they were ordered by different institutions in different cities at different times,” he said.

“Besides, most have been forgotten over the years and publishers have resumed printing the banned books.”

As an example, the complete works of Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, who died in exile in Moscow in 1963, had already been stocked in libraries for years despite the ban.

The reform is thus largely symbolic, and some are sceptical of whether it reflects any true change within the Turkish state.

“The mindset hasn’t changed and people (in the administration) will continue to do whatever they think is right,” said Omer Faruk, a former head of the Ayrinti publishing house.

He cited as an example the fate of one of his published books: the erotic “Philosophy in the Bedroom” by French writer Marquis de Sade.

Deemed licentious, the text was banned, but the Supreme Court overturned the decision. Yet “despite the ruling, the book continues to be seized”, Faruk said.

This scepticism is reinforced by the ruling Islamic-rooted Justice and Development Party’s record in matters of freedom of speech.

The Committee to Protect Journalists said last month that Turkey had, at 49 people, the highest number of journalists behind bars, with most of them Kurds.

In late November, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself took the directors of a television series to task, saying their script was in conflict with history and Muslim morals.

“Those who toy with the people’s values must be taught a lesson,” Erdogan said.

But despite his reservations, Zeynioglu said there would be at least one concrete result of letting the bans lapse.

“Many of the students arrested in demonstrations are kept in prison because they’re carrying banned books,” he said.

“From now on, we won’t be able to use that as an excuse.”