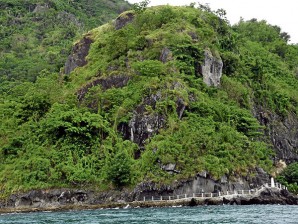

NOT WANTING to climb a steep hill such as this one in the northern Iloilo town of Concepcion, schoolchildren were called “spider kids” because they would rather cling to seawalls and brave raging waters below them just to get to school.

Just to get to school, two to three children as young as 6 years old would cling daily in groups to a rough and spiky seawall.

They look like spiders, slowly inching their way for 15 meters until they get to the safe part of the beach trail leading to the nearest primary school.

Mark Nene and his best friend, Josil Apruebo, now both 18, recall that they had no choice then. Going to school the “safe way” meant taking a risk of being late since they had to climb a steep hill and walk for 1.8 kilometers.

Thus, they would rather be spider boys and get slapped by the waves hitting the seawall or brave swimming the six-meter deep, and occasionally raging waters in case they did fall—as generations before them had endured.

Thing of the past

The daily prayers and supplications of parents and grandparents on the island barangay of Macatunao in Iloilo’s Concepcion town were answered as no child had drowned although many did come home bruised and drenched.

This fact of life for schoolchildren in Sitio Balabago is now a thing of the past.

A housewife pawned her wedding ring and braved two typhoons so she could present a proposal for a cement foot trail connecting her village to the primary school.

COMMUNITY volunteer Vivian Dolor is instrumental in the construction of a cement foot trail.

Vivian Dolor, 40, remembers that from age 6 to 12, she was a “spider girl” since she and her friends would cling to the cliff wall and got bruises or drenched by waves just to get to Bagotao Primary School. That had been her routine until she completed her primary education.

“I pitied my son and the other children coming home with their drenched bags and clothes and I thought, if nearby Sitio Bagotao could have a barangay trail built when our sitio (Balabago) had the more dangerous portion of the seawall, why can’t we do something about it?” Dolor says.

She finished a vocational course, Associate in Business Data Processing, at Computer College of the Visayas in Iloilo City.

A volunteer of the government program Kalahi-CIDSS (Kapitbisig Laban sa Kahirapan-Comprehensive and Integrated Delivery of Social Services), Dolor and the Macatunao barangay council then prepared a proposal for the construction of a 50-meter cement trail from Balabago to Sitio Bag-ong Tawo at a cost of P1.158 million.

On Oct. 14, 2010, Dolor had to be in Concepcion town proper to present the proposal at a two-day municipal interbarangay forum.

MARK Nene, 18, demonstrates how he used to cling to the seawall and inch his way through 15 meters of rough and spiky rock just to get to the nearest primary school.

But two typhoons threatened to derail her 30-minute pump boat ride to town. She, along with barangay chair Imelda Gregorio and project preparation team leader Rami Padecio, insisted on pushing through with the trip.

The three were drenched when they arrived at the mainland. They, however, realized that they didn’t have enough money to prepare for the presentation.

Wedding ring

Dolor took out her wedding ring and pawned it for P3,500. She used the P500 to buy materials for the presentation, as well as to develop the photographs they took to prove how much Balabago needed the foot trail.

“I knew that if we did not present the proposal that time, we would not be able to get the funding and the opportunity to have a cement foot trail might be forever gone,” Dolor says with a sheepish smile.

But their sacrifices paid off: the Kalahi-CIDSS approved their P1.158 million budget.

Construction of the cement foot walk started on March 7, and the project was finished just in time for the school opening in June—free labor coming from the men of the community who themselves in younger years braved the spiky seawall and the rough waters to get to school.

Happy with the outcome, Dolor does not mind that up to now, her ring remains at the pawnshop.

Bag-ong Tawo, where the primary school is, now lives up to its English name—“hamlet of the newborn.”

PHOTOS BY GUIJO DUEÑAS/CONTRIBUTOR