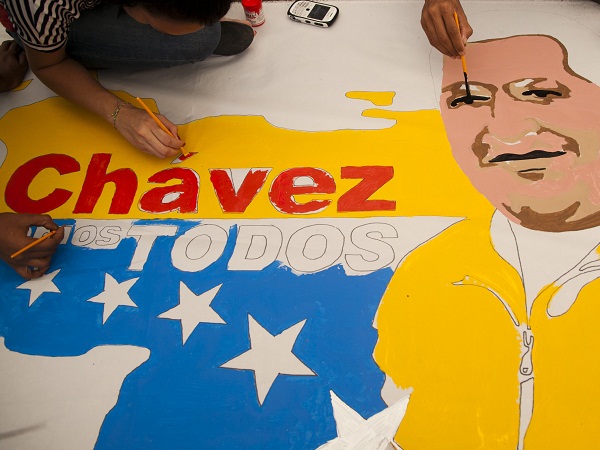

Supporters of Venezuela’s President Hugo Chavez create a poster with his image alongside an outline of their country in Caracas, Venezuela, Friday, Dec. 14, 2012. Chavez’s most influential allies are projecting an image of unity while the president recovers from cancer surgery in Cuba, standing side-by-side and pledging to uphold his socialist movement no matter what happens. AP/Ariana Cubillos

CARACAS, Venezuela—Hugo Chavez’s cancer has upended politics in Venezuela, transforming Sunday’s nationwide elections for state governors and legislators into a test of his legacy that could chart the country’s future in the uncertain months ahead.

For the first time in his nearly 14 years in power, the charismatic, voluble Venezuelan president has been unable to actively participate in such a campaign.

The question now hovering over the vote: Will his illness help or hurt the ruling apparatus he has built almost singlehandedly and strengthen his leftist agenda?

If Chavez’s camp can maintain dominance in the country’s 23 governorships, all but eight of which it holds, it can forge ahead with plans to solidify his “socialist revolution” by fortifying grass-roots citizen councils that are directly funded by the central government.

Chavez’s backers have framed the election as a referendum on his legacy, angling for the sympathy vote.

For the opposition, the elections are apt to determine the fate of its leadership. The most pivotal race involves Henrique Capriles, who gave Chavez his stiffest challenge yet in the Oct. 7 presidential election by winning 44 percent of the votes.

If Capriles, 40, can win re-election as governor of Miranda state, which includes parts of the capital, the grandson of a Polish Holocaust survivor would be the opposition’s most likely choice in the event of a presidential election that would need to be called within 30 days if Chavez died. Even before Chavez’s mortality became a factor, the Miranda race was considered crucial for the opposition with Capriles facing Elias Jaua, Chavez’s former vice president.

Chavez has virtually monopolized power in his person, painting much of the country red, the color of his leftist movement, as he nationalized key industries and expropriated private land.

The man he designated to succeed him before flying to Cuba last Sunday for cancer surgery, Vice President Nicolas Maduro, is a political lightweight by comparison. Capriles is widely seen as having a far better chance against Maduro than against Chavez.

Another key race is in Zulia state, Venezuela’s most populous, where opposition Gov. Pablo Perez is running for re-election.

David Smilde, a University of Georgia sociologist and analyst for the Washington Office on Latin America think tank, believes Capriles will hold on to Miranda’s governorship. But he expects an unusually high turnout Sunday that he believes will favor the Chavistas, even among voters fed up with high-level corruption in the president’s inner circle.

Many Chavistas have been moved by the president’s plight, and some pro-Chavez candidates have been calling for people to vote for them in a show of support and solidarity.

“It is now about Chavez and his legacy,” said Smilde. “And there is a lot of sympathy.”

Smilde said the woman who cleans his Caracas apartment complains about Chavez but, after news suggesting his cancer was incurable, “she was talking to me with her eyes moist about Chavez and how she’s going to vote for Elias Jaua, and that kind of surprised me and I tend to think it’s not isolated.”

Gladys Espinal, who recently completed studies at the free, state-run Bolivarian University to be a schoolteacher, was also voting for Jaua.

“The (electoral) map is going to be filled with red because that’s the best gift we can give our president,” she said in a downtown Caracas bakery.

Chavez’s health has become such a factor in the vote that pocketbook issues like growing public debt and a scarcity of dollars that’s pushing up the prices of foreign goods are falling to the side.

In the past, the opposition has fared better in regional elections than in presidential votes because it could hone in on nuts-and-bolts issues such as the plethora of unfinished public works projects under Chavez or citizen insecurity.

Smilde noted the big popularity boost that followed Chavez’s re-election to another six-year term: 68 percent approval in an early November poll by the Datanalisis firm.

And that’s before he announced he would need a fourth surgery for a cancer first diagnosed in mid-2011.

Candidates of the governing Unity Socialist Party of Venezuela have campaigned on strengthening communes, which are grass-roots citizen councils that receive their funding directly from the central government.

It’s a mechanism that has allowed Chavez to bypass state and municipal control and build loyalty, or dependency, opponents say, among the working poor through government goods and services they never had before. Free health care, subsidized food and access to free education have proliferated under the system.

If the Chavistas gain or even hold steady Sunday, the executive branch could strengthen its hold on the grass roots, as communal councils decide, often based on loyalty, such questions as who gets a new roof, or who receives vocational training, distributing the funds directly.

“The idea is a gigantic state that controls everything,” said Angel Alvarez, a political scientist at Venezuela’s Central University.

Chavez, 58, underwent six hours of surgery in Havana on Tuesday that government officials said involved bleeding, which was stanched, and would mean a difficult recovery.

Analysts say his absence during campaigning could hurt Chavista candidates in Sunday’s elections, especially relative newcomers who in the past could count on the president accompanying them on the hustings.

Government officials have been doing their best to compensate.

They have been holding vigils for Chavez all week, hanging banners in tribute and broadcasting elegiac footage on state TV of the former army lieutenant colonel who first gained celebrity by leading a failed 1992 coup.

Capriles complained this week of the government using Chavez’s failing health for political leverage, citing Jaua’s statement that “people should vote Sunday for the president’s recuperation.”

“The leadership of a single person is not transferrable,” Capriles told reporters.

Smilde, for one, expects whomever the Chavistas choose as their candidate to win any presidential election that would be called if Chavez, who is due to be inaugurated Jan. 10, dies in the next few months.

After that, many analysts believe the country could slide into economic turmoil as a fiscal hangover bites from Chavez’s huge social spending last year. By law, presidential elections must be called if Chavez dies in the first four years of his six-year term.

Opposition congressman Julio Borges, who leads the Primero Justicia party, called Sunday’s elections “just another piece on the chessboard of a country that is going to suffer very profound changes in the coming months.”

He predicted a split electoral map, which he called the beginning of the end of Chavismo as “the president is going to be disappearing from the scene little by little.”

In addition to choosing state governors, voters will also be selecting 229 members of state legislative councils.

Francisco Sanchez, a 45-year-old refrigerator salesman, said he hoped the opposition would have an edge Sunday as Chavez’s one-man rule ebbs. But he fears divisions within it.

“We must remember that the only thing that unites the opposition parties is their desire to get rid of Chavez,” he said.

Associated Press writers Chris Toothaker and Ian James in Caracas and Frank Bajak in Bogota, Colombia, contributed to this report.