“I really love her,” Adlawan said as he narrated how close they were since their teenage years when they first met. Their union bore seven children.

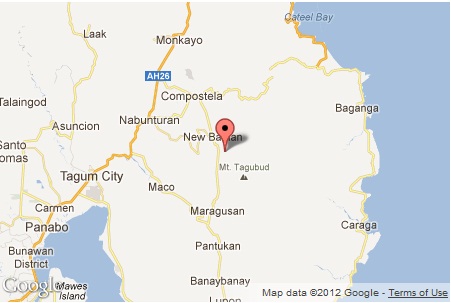

Carmelita, along with one of their daughters and two grandchildren, went missing when Pablo lashed at this town. They had not returned home since or had been found alive.

His son Pedro lost his entire family.

“Bebing, who is my son’s wife, is missing and also one of their children. Their other child was found dead,” he said.

“I cry almost every morning,” Adlawan said of his emotional state since Carmelita and their kin disappeared at the height of typhoon Pablo.

He said he should gather the strength to move on now, although he has been deeply disturbed by the thought that “I have not seen them given proper burial.”

Elsewhere in the town, many people like Adlawan have started coming to terms with reality: missing kin, numbering nearly 476, who might not have any chances of getting back home alive anymore.

About 250 bodies had already been recovered in this town alone.

“Those unidentified corpses would be buried in one of the graves, while the identified bodies into the other hole. The graves are made in concrete due to health and sanitation concerns,” Marlon Esperanza, municipal information officer, said.

A young woman on Tuesday approached Esperanza’s desk to check if her father was among those listed as dead.

“It’s been more than a week already and I don’t think he would still be found alive,” the woman from worst-hit Andap village, said as she browsed the long list of dead victims written on a cartolina and tacked near the makeshift information center at the town proper.

“Until his body had been found and positively identified, we cannot just yet include him on the list of dead (victims),” Esperanza replied.

A few number of survivors said they would only give up hopes of finding their relatives alive if their bodies were found.

“I will only return (to our village) if mother and my family had already returned,” Pedro said.

Other victims are now prioritizing keeping their surviving family members alive by promptly lining up for relief goods at distribution centers.

Violy Saguing, 38, who lost her eldest child Rodyard to the disaster, said living in an evacuation center has been difficult and lining up for relief goods has compounded their suffering.

“It is so hard to fall in line,” a sobbing Saguing said when the Philippine Daily Inquirer saw her.

“My husband, who is an office worker, joined a volunteer group that repacks goods for distribution. But he could not directly hand me the food items needed to keep our children away from hunger. I still have to fall in line,” she said.