There was an abrupt halt to my early morning rituals on my last Saturday in Oman.

I just quit my job. I did not have to rise at half past seven, smoke buri (traditional Omani tobacco pipe) twice, take a quick shower, brush my teeth, get dressed, hail a shared taxicab to the college, sip a cup of hot Nescafé in my cubicle while checking my e-mail and browsing local news back home and, finally, fine-tune my lesson plans.

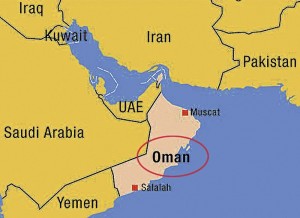

On that very last Saturday, I thought about the teaching I did—and was asked to do—for the last eight months in this beautiful desert country. Though cut short, my teaching stint could not have been more interesting and insightful.

I did learn a lot.

I learned what “context” meant in relation to English pedagogy—finally! Until I stepped into the classrooms of a college in Oman, teaching young Omanis, many of whom were Bedouins (members of nomadic Arab tribes), this word was just a theoretical notion that we had discussed in the English department of Ateneo de Manila University a few years back.

I learned further that local contexts—local modes of learning, knowing and being—should essentially dictate, shape and inform a teacher’s classroom practices, that teaching implements and curriculums borrowed (and self-imposed) from the West often did not fit into the natives’ unique framework of understanding themselves and the bigger world.

Tweaking topics

Skipping and often tweaking a bit (out of constant pressure from the management) topics that could not be any “whiter”—values, practices and beliefs held by people from the West—became my alternative.

I learned, painfully, to come to terms with the outsiders’ gaze into my classroom rituals. Though I despised their often prescriptive and objectifying motives, I left the door ajar to admit a shred of truth in what administrators said about my teaching.

Totally brushing their observations aside would be naive.

To my boss I said: “OK, I kind of agree with what you say about the psychology in classroom seating arrangement and, yes, please give me a minus point for the mess that you saw two days ago.”

I learned to abandon big words on the philosophy of education and pedagogy. Not that they were irrelevant, but I felt there were real and tangible issues that needed immediate attention and action. Intellectualizing them in prolonged deliberations with colleagues did not really prove fruitful.

Always getting in the way was an enemy called time. There was just not enough time to counter these forces amid lesson planning, teaching, testing, vetting, keying of marks, meetings and endless paperwork.

Out there were stable and strong sociocultural forces that predetermined and limited what could be done in the classrooms. And they will always be there!

Eventually, it became less difficult for me to submit to the demand for too much paperwork, which had little to do with actual teaching. I could not always have things my way.

I learned that despite the rigid curriculum and disciplinary measures meant to keep the academic community in order, I could tap into microsites for possibilities for resistance.

I learned that those sites were sacred spaces that must be defended against all forms of sacrilege from outsiders. They were my last refuge and territory, and I could never allow anyone to trespass.

Localizing English

In these little fleeting sites, for example, I managed to encourage the use of localized English to underscore its legitimacy as a variety of world English.

“Big problem, mafi good,” I’d tell my students whenever they played truant or did not do their homework.

I finally learned that, despite years of experience, teaching would always be a whole new investment—an entirely new web of social practices. No theory or a constellation of such could ever fully grasp its fluidity, complexity and uniqueness in a given context.

That Saturday morning, which marked the end of my teaching journey in Oman, I had mixed feelings. My heart was both light and heavy.

I had done much of what I set out to do. I was able to devise a language only my students and I understood. That special language served as a bridge between my tiny universe and theirs.

I could and wanted to do more. I wish there were more Saturdays to come. But it was time to move on to some distant place awaiting me out there.

(Editor’s Note: A simple village lad from Lipa City, the author is a “nomadic” teacher exploring local cultures overseas to expand his critical and creative pedagogical repertoire.)