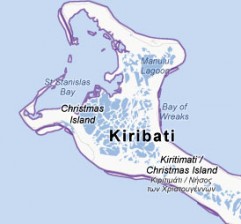

‘Time running out’ for Kiribati as seas rise, says president

Photo from google maps

WELLINGTON – The low-lying Pacific nation of Kiribati is running out of time on climate change as seas rise, and is drafting plans including mass relocation of its people while the world procrastinates on the issue, the country’s leader says.

President Anote Tong said areas of Kiribati — consisting of more than 30 coral atolls, most only a few metres (feet) above sea level — had already been swamped by the rising ocean.

“We’ve had communities that have had to relocate because their previous village is submerged, it’s no longer there,” he told AFP in a telephone interview from the capital Tarawa.

“We had a very high tide at the beginning of this month and communities were washed out. It’s becoming more frequent, time is running out.”

Kiribati is among a number of island states — including Tuvalu, Tokelau and the Maldives — the UN Human Rights Commission is concerned could become “stateless” due to climate change.

Article continues after this advertisementWith erosion gnawing at the coast and crops dying as sea water infiltrates fresh water sources, Tong said plans to relocate people from Kiribati to Fiji and East Timor had been put forward.

Article continues after this advertisementHe was pessimistic UN climate talks underway in Doha would offer a solution, saying they assumed global warming would occur in the future, allowing countries to stall over emissions targets.

“That’s not relevant to us,” he said. “The reality is that we’re already facing problems.

“Are the negotiations addressing this? I don’t believe so. They’re regarded as a game by many of the negotiators, they’re not focusing on what’s already happening in the most vulnerable countries.

“We (in Kiribati) are not talking about economic growth, we’re not talking about standards of living — we’re talking about our very survival.”

— “Some of our people will have to be relocated” —

Rather than wait for global action, Tong said Kiribati was examining options for the climate-threatened nation, including relocating parts of its 103,000-strong population.

The best scenario involves building sea walls and planting mangroves to repel rising seas, allowing life in Kirbati to continue much as it has for centuries.

Tong said that was unlikely, with data released last week finding seas rising quicker than previous estimates, pointing to a one-metre (3.25 foot) rise by the end of the century.

Other options involve moving all or part of Kiribati’s population elsewhere.

“We have to accept the possibility, the reality, that some of our people will have to be relocated,” Tong said.

“We don’t want to allow the nation of Kiribati to disappear and we have to work out what we do in order to ensure that.”

— Fears Kiribati “collateral damage” in climate debate —

He said the government was set to purchase 2,000 hectare (5,000 acre) of land in Fiji, to provide food for Kiribati and possibly act as a new island home.

“We’re looking to buy that piece of land as an investment for food security issues,” he said. “But if all the land we’re staying in now (Kiribati) was totally swamped, maybe it would provide an alternative in the future.”

He said impoverished East Timor had also offered land if needed.

Tong said man-made islands were an expensive option, but remained a possibility if the global community helped foot the bill to prevent Kiribati becoming “collateral damage” to climate change.

“Man-made islands are expensive but climate change itself is expensive, it could cost the future of this planet,” he said.

Tong expects an options paper to be completed early next year, with detailed costings and engineering reports that could be presented to potential donors.

He said there was no “D-day” for a decision about relocation, instead seeking to allow residents a choice about whether to stay or leave.

“To wait for the time when we have no other option but to jump (in the sea) and swim or go somewhere is unrealistic,” he said.

— “I refuse to give up on humanity —

After arguing for urgent action on climate change at numerous international forums since winning power in 2003, Tong said he would not attend the Doha talks.

“The question is what to say next to galvanise the international community into action?” he said. “Sometimes there’s a deep sense of frustration, sometimes a sense of futility.

“We’ve got to talk to people who will listen, not people who will just give you an excuse.”

However, he remained optimistic the world would help countries such as Kiribati, which did not cause climate change but bore the brunt of its effects.

“I think the citizens of countries have a conscience but they’re not really the ones who make these decisions… It’s the governments,” he said.

“We need to keep talking to the people and can’t lose faith in humanity. I refuse to give up on humanity.”