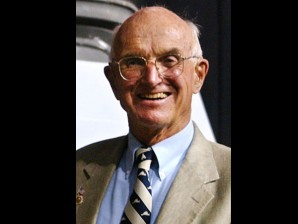

This July 28, 2004 file photo shows Dr. Joseph E. Murray, who performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant and won a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work, has died at age 93. AP FILE PHOTO

BOSTON – Dr. Joseph E. Murray, who performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant and won a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work, has died at age 93.

Murray’s death in Boston was confirmed Monday by Brigham and Women’s Hospital spokesman Tom Langford. No cause of death was immediately announced.

Since the first kidney transplants on identical twins, hundreds of thousands of transplants on a variety of organs have been performed worldwide. Murray shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990 with Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, who won for his work in bone marrow transplants.

“Kidney transplants seem so routine now,” Murray told The New York Times after he won the Nobel. “But the first one was like Lindbergh’s flight across the ocean.”

Murray’s breakthroughs did not come without criticism, from ethicists and religious leaders. Some people “felt that we were playing God and that we shouldn’t be doing all of these, quote, experiments on human beings,” he told The Associated Press in a 2004 interview in which he also spoke out in favor of stem cell research.

In the early 1950s, there had never been a successful human organ transplant. Murray and his associates at Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, now Brigham and Women’s Hospital, developed new surgical techniques, gaining knowledge by successfully transplanting kidneys on dogs. In December 1954, they found the right patients, 23-year-old Richard Herrick, who had end-stage kidney failure, and his identical twin, Ronald Herrick.

Because of their identical genetic background, they did not face the biggest problem with transplant patients, the immune system’s rejection of foreign tissue.

After the operation, Richard had a functioning kidney transplanted from Ronald. Richard lived another eight years, marrying a nurse he met at the hospital and having two children.

“Post-operatively the transplanted kidney functioned immediately with a dramatic improvement in the patient’s renal and cardiopulmonary status,” Murray said in his Nobel lecture. “This spectacular success was a clear demonstration that organ transplantation could be life-saving.”

Murray performed more transplants on identical twins over the next few years and tried kidney transplants on other relatives, including fraternal twins, learning more about how to suppress the immune system’s rejection of foreign tissue. One patient who received a kidney transplant from a fraternal twin in 1959, plus radiation and a bone marrow transplant to suppress his immune response, lived for 29 more years.

But it was the development of drugs to suppress the body’s immune response, a less radical approach than radiation, that made real breakthroughs in transplants possible. In 1962, Murray and his team successfully completed the first organ transplant from an unrelated donor. The 23-year-old patient, Mel Doucette, received a kidney from a man who had died.

Murray continued a long career in plastic surgery, his original specialty, and transplants. He was guided by his own deep religious convictions.

“Work is a prayer,” he told the Harvard University Gazette in 2001. “And I start off every morning dedicating it to our Creator.”

Murray told the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2004 that he continued to get letters from patients he had helped years earlier and from relatives of those who died during the early efforts.

“They often say … that they are happy to have played some small part in the eventual success of organ transplants,” he said, praising the courage of his patients and their families.

Murray was honored at the 2004 Transplant Games, for athletes who have received organ transplants, along with Ronald Herrick, the man who had donated a kidney to his twin brother a half-century earlier.

Murray’s interest in transplants developed during his time in the Army during World War II when he was assigned to Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania while awaiting overseas duty. The hospital performed reconstructive surgery on troops who had been injured in battle.

The burn patients, who were often treated with skin grafts from other people, intrigued Murray.

“The slow rejection of the foreign skin grafts fascinated me,” Murray wrote in his autobiography for the Nobel Prize ceremony. “How could the host distinguish another person’s skin from his own?”

The hospital’s chief of plastic surgery, Col. James Barrett Brown, had performed skin grafts on civilians and noticed that the closer the donor and recipient were related, the slower the tissue was rejected. A skin graft between identical twins had taken permanently.

Murray said that was “the impetus” for his study of organ transplantation.