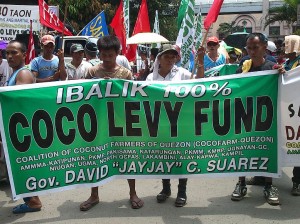

Coco levy farmers trooped to the Supreme Court and asked Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno to investigate SC’s conflicting decisions on coco levy.

There’s a sense of déjà vu in the Aquino administration’s plans for some P100 billion in recovered assets illegally acquired with funds from the coconut levy imposed during the martial law years.

The refrain coming out of the government that the money should now be used “for the benefit of the farmers” has a familiar ominous ring.

It is similar to the series of decrees the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos promulgated beginning in 1973 that gave rise to a coconut consumer stabilization fund, a coconut industry development fund, a coconut industry investment fund—all on the pretext that they would improve the lives of the farmers.

In fact, say critics, the measures solely enriched close business associates of the martial law regime, beyond their wildest dreams.

Oscar Santos, 84, a former congressman who has been at the forefront of the struggle for reforms in the industry, one night went over a thick file of Marcos decrees and letters of instruction concerning the coconut levy. He fell asleep after he counted at least 82 times that the edicts were supposedly “for the benefit of the farmers.”

Nearly 40 years on, the nation’s 3.5 million farmers remain impoverished, the 20 million people dependent on the coconut industry are classified as among the poorest of the country’s poor, and the coconut trees are increasingly becoming more senile and barren, unable to meet growing world demand.

On Friday, San Miguel Corp. (SMC) redeemed 24 percent of its shares of stock worth nearly P70 million that had been sequestered since the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution for allegedly being part of the ill-gotten wealth of Marcos and his cronies.

The buyback came after the Supreme Court in a decision on Sept. 4, released to reporters two weeks later, dismissed a motion for reconsideration and voted to uphold with finality a ruling on Jan. 24.

Voting 11-0, the court declared that the SMC assets in the name of 14 holding companies set up under the Coconut Industry Investment Fund (CIIF) and the Oil Mills Group (OMG) were purchased using the coconut levy and are therefore “owned by the government to be used for the benefit of all coconut farmers and for the development of the coconut industry.”

It was the biggest recovery of alleged illegally stashed wealth of Marcos and his cronies, according to the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) that was set up precisely to recover such assets.

In anticipation of the final favorable ruling, the administration set up a presidential task force chaired by the head of the National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC), Joel Rocamora, to prepare a road map for the utilization of the fund.

Better a loaf than nothing

In a statement, Sen. Joker Arroyo said that the arrangement “will not do justice to the small coconut farmers.”

“This could be a repeat of the martial law edict in 1973 that imposed a levy on the coconut produce of the farmers. The levies helped the industry; coco mills were put up, a coconut bank was established, coco deposits were loaned to acquire the controlling stock of San Miguel. But that did not benefit the coco farmers. After Edsa, the impoverished farmers complained and a 26-year court struggle ensued,” he said.

Arroyo continued:

“The case has been decided. The industry players are extremely happy; the farmers are disillusioned. But better a loaf than no bread at all.

“Will the farmers get their monies back? No. Not yet. How much, if at all? The task force will determine that.

“The pivotal question: How much will go to the industry and how much will go to the farmers, the twin beneficiaries according to the Supreme Court?

“The lopsided composition of the task force is very discouraging. It is similar to the 1973 committee that gave birth to the coco levy fund—heavily tilted in favor of the industry and the underrepresentation of the farmers.

“As to the farmers, what is important is the cash component that goes to them. Will the farmers wait until the coconut industry is rehabilitated and create employment for them? That was the carrot that was waved to them in 1973.”

The task force has met 10 times, the Philippine Daily Inquirer has learned. The last meeting at Malacañang was on Thursday, a day before Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco, SMC chair and uncle of President Aquino, handed out the check for P56.5 billion for the 753 million shares of stock, designated as CIIF-OMG shares comprising 24 percent of one of the nation’s highly diversified conglomerates, plus P13.44 billion in dividends and interests.

Joke of the century

This SMC block of shares was part of the 47 percent of SMC shares acquired to the tune of P2 billion in a complex scheme behind the glare of the Marcos-controlled media in 1983. It was conjured by Cojuangco’s battery of top lawyers that set up scores of dummy companies under whose names the stock certificates were issued. The shares were seized by the PCGG after Edsa I.

In April last year, the court ruled that a 20-percent block of SMC shares belonged to Cojuangco, dismissing allegations that it was part of the Marcos ill-gotten wealth and claims that the businessman was a Marcos crony.

The ruling also shrugged off claims that as then president of state-owned United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB), Cojuangco had a fiduciary trust over the levy funds deposited in the bank—to protect the money, not gain from it. This block of shares is worth P54.36 billion of common shares (based on P110/share).

A dissenting justice called the ruling “the biggest joke to hit the century.”

Originally representing 27 percent of the SMC stock, the CIIF-OMG shares became a 24-percent block. It was diluted in proportion to the total San Miguel equity when the then food and beverage giant expanded upon the entry of Kirin Brewery of Japan.

The entire sequestered shares of SMC stock had actually reached 51 percent of the conglomerate’s equity, including 4 percent in treasury warrants that the former SMC boss Andres Soriano used as down payment for an attempted buyback in April 1986 of the seized assets. Last year, the PCGG asked the Supreme Court to direct SMC to turn over these treasury warrants worth P15 billion, the Inquirer has learned, but the high tribunal has yet to issue such an order.

Gross ignorance of law

Joey Faustino, executive director of the Coconut Industry Reform Movement, has not given up the fight against Cojuangco’s 20-percent block of shares, which had been sold to SMC president Ramon Ang after the court decision on the case became final in May.

Faustino’s group, as well as other organizations, including the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, has sent a letter to Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno asking for an investigation primarily of the ponente, or assigned writer of that ruling on the Cojuangco case, Associate Justice Lucas Bersamin, for possible gross ignorance of the law, knowingly rendering an unjust judgment and other alleged violations of ethical standards.

“As far as the coconut farmers and the public are concerned, no null and void decision can ever be declared final,” Faustino said.

He noted that under the Arroyo administration, the farmers lost some P50 billion in the conversion of the 24-percent block of SMC shares from common to preferred shares. He vowed to make the authors of the conversion accountable.

Faustino also slammed the PCGG under President Aquino for doing nothing about the conversion.

He said Cojuangco’s allies in Congress were blocking legislation for the setting up of a trust fund to protect the recovered levy funds and that CIIF president Jesus Arranza, who is linked to the businessman, was now talking about using the money for research and development of the coconut industry.

“The fact is that the proceeds of the redemption of the shares, cash dividends included, are all now in the hands of the the UCPB-CIIF group of companies that once ruled the monopoly,” Faustino said. “History repeats itself.”