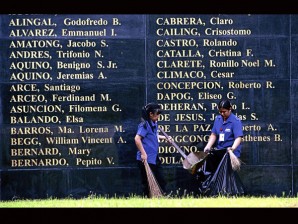

DOZENS of names of men and women who fought the Marcos dictatorship are etched on the Bantayog ng mga Bayani memorial that was built for people who resisted one-man rule. Thousands of others who gave up their lives for the return of democracy remain nameless. MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—Forty years after the dead dictator Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law, there is still no complete accounting of victims of abuses during his one-man rule.

“It’s correct to say there is no final inventory yet. It’s being done. We’ve been trying to look for all [victims],” said Josephine Dongail, a member of the board of the Samahan ng mga Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto (Selda).

Dongail, who is in charge of the documentation project, said the compilation of the list began in 1987 through an Amnesty International survey.

This produced a list of at least 10,000 victims who were killed, abducted, illegally detained and arrested or tortured by government soldiers and policemen and other state agents.

“The list is incomplete because during the Cory (former President Corazon Aquino) and Ramos (former President Fidel Ramos) periods, it was terrifying to be in the provinces,” said Dongail, who was detained in 1978.

Lack of resources

The lack of resources makes the search doubly difficult.

Max de Mesa, chair of the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (Pahra), said the human rights community has only records prepared by the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (TFDP), Bantayog ng Bayani Foundation and Karapatan.

“A complete list of victims is not yet available so far,” De Mesa said.

The period being reckoned with is from Sept. 21, 1972, when Marcos declared martial law through Proclamation 1081, to Feb. 25, 1986, when the strongman fled on the heels of the People Power revolt at Edsa.

Isafp files

The files turned over by the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (Isafp) to the Commission on Human Rights last year contained mostly policy papers, intelligence reports and results of monitoring of anti-Marcos rallies, said De Mesa, who stood in as witness in the turnover.

“There was no list even of detainees kept in prison camps in the regions,” he said.

“Closure is difficult because there is no transparency in the security force. This is where the Freedom of Information bill can help. We need to have closure,” he said.

Pahra has no estimate on the number of human rights victims during martial law while Selda’s list counted over 20,000.

Identities

The recording is being done mainly to identify the thousands of people who suffered various forms of abuses during Marcos’ rule, said Dongail. “They cannot be nameless forever,” she said.

De Mesa said the quest for justice is especially important for relatives of victims of enforced disappearances. “They would like to know where their loved ones are buried so they could give them proper burial,” he said.

The Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance (Find) has documented 1,838 victims from the Marcos regime to the Aquino administration.

Nilda Lagman-Sevilla, Find cochair, said many activists could have gone unrecorded, especially in the provinces.

Guerrilla zones

In guerrilla zones alone, the number of victims of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances from 1983 to 1986 reached 5,000, said Rodolfo Salas, chair of the Communist Party of the Philippines and head of the New People’s Army from 1976 until he was arrested on Sept. 29, 1986.

“The party received reports from time to time but it was difficult tracking incidents in urban areas because the military had shifted from using prison camps to safe houses,” Salas, also known as “Kumander Bilog,” told Inquirer on Monday.

Loretta Ann Rosales, chair of the Commission on Human Rights, said the CHR relies on information from TFDP, which has documented some 3,000 victims.