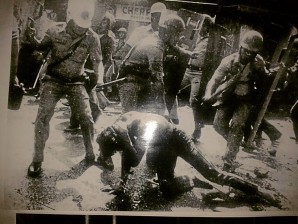

THIS PHOTO of police brutality on protesters is among those displayed in the exhibit, “Himagsik at Protesta,” put up by Karapatan at the University of the Philippines Library until Sept. 21 for the 40th anniversary of the declaration of martial rule. PHOTO REPRODUCTION BY TONETTE OREJAS

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—At 92, Cecilia Castelar-Lagman died on Aug. 13 without finding her son, Hermon, a labor and human rights lawyer during martial rule.

Must be because she was a public school teacher or a devoted mother, Lagman showed exceptional tenacity during the 35 years she had looked for Hermon, says her daughter, Nilda Lagman-Sevilla.

She never surrendered Hermon, then 32, to oblivion ever since a group of men, believed to be soldiers, abducted him and labor leader Victor Reyes on May 11, 1977, on the heels of successful strikes waged by his clients, the 10 labor unions that openly defied the strike ban during martial rule imposed by strongman Ferdinand Marcos, Sevilla says.

In the depth of her grief, she drew courage from the Tayag, Crismo, Yap, Ontong, Del Rosario, Pardalis, Reyes and Romero families whose relatives were “desaparecidos” (involuntarily disappeared) like Hermon. The Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (TFDP) was their beacon of hope, guiding them in their search.

Sevilla says that although Marcos lifted martial law in 1981 to put up a humane front ahead of the visit of Pope John Paul II, the nine families founded the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND) in 1985 as repression heightened and the ranks of the missing swelled.

“They began with personal crusades and embarked on a collective crusade that continued even after martial rule of Marcos,” says Sevilla.

Weeks before her death, Lagman consented to make a film on the life of Hermon to make the younger generation remember martial rule and gain lessons from it.

“She looked forward to watching it and she said, ‘I will watch it and I’m ready to cry over and over and over again. I have not run out of tears for Hermon,’” Sevilla says. Lagman’s son, Felimon, more known as “Ka Popoy” in the revolutionary socialist movement, was murdered in 2001.

Failure of martial rule

Sevilla, now FIND cochair, says efforts of Lagman and the eight families to pursue the causes of the desaparecidos and their kin speak of what martial rule failed to do: Silence everyone into fear and inaction.

“It’s an uphill battle,” Sevilla says of finding political

activists.

Aside from looking for the victims and recovering their remains, the FIND has lobbied in the last 16 years for the passage of a law to classify involuntary disappearance as a criminal offense.

The lobby reached a positive turn in March when Congress passed House Bill No. 98 on third and final reading. The principal author is Albay Rep. Edcel Lagman, Hermon’s younger brother.

Sevilla says the Philippines has yet to sign the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (Icpaped).

HB 98 adopted Icpaped’s definition of involuntary disappearance: “The arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or group of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

Without letup

Martial rule or not, enforced disappearances continue without letup, FIND data show.

Under Marcos, the number of documented victims reached 878, beginning with the first victim, Charlie del Rosario, one of the founding members of the Kabataang Makabayan.

The FIND counted 614 victims during the administration of President Corazon Aquino from 1986 to 1992; 94 during the term of President Fidel Ramos from 1992 to 1998; 58 in the time of President Joseph Estrada from 1998 to 2001; 182 during the nine-year reign of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo; and 12 under President Aquino.

At least 435 victims have surfaced alive while 256 others were found dead, providing closure to their families. Most of the victims were men, with women making up 9 percent. Many of the victims were farmers, workers and youths.

Regions with high incidence of documented cases are Western Visayas, Western Mindanao, Southern Mindanao, Northern Mindanao, Metro Manila and Central Luzon.

But justice is hard to come by even to those who have been able to identify their captors and torturers in the military or police, Sevilla says. Several of these officers had been promoted, case studies showed.

Following the path of the founders, the FIND has organized the families, drawing 1,100 members from among them. The families helped each other as some undergo trauma reduction or start livelihood programs.

“Many mothers and children are resilient and they serve as pillars of strength,” Sevilla says.

Corazon Estojero and Grace Topacio have not given up on their husbands, Edgardo and Renato, respectively, pursuing their quest for justice by working as FIND volunteers.

“The desaparecidos are martyrs because they have stood up against regimes that violated the socioeconomic and political rights of Filipinos. You cannot expect an end to desaparecidos or extrajudicial killings because the conditions to quell the protest of the people are still around,” Sevilla says.