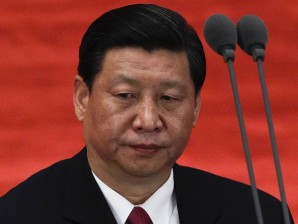

In this May 4, 2012 photo, Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping attends a conference to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the founding of Chinese Communist Youth League at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China. Xi has not been seen in public since September 1, fueling speculation that he suffered a health crisis that forced him to cancel meetings with Hillary Clinton and others. AP/Alexander F. Yuan

BEIJING — China’s missing leader-in-waiting, Xi Jinping, was mentioned Thursday in an official newspaper report, state media’s only reference to him since he dropped from sight 12 days ago, sparking rumors of illness.

The Guangxi Daily referred to Xi in its report on the death last week of 102-year-old former general Huang Rong. It said Xi, President Hu Jintao and other top officials had expressed their condolences “through various means,” but gave no other details.

Identical reports were carried on the websites of the Communist Party and the official China News Service.

Xi, China’s vice president, is due to take over as Communist Party head later this year and as president in the spring as part of sweeping transition to a new generation of leaders.

The government has offered no information on why he dropped from sight and canceled several public appearances, sparking rumors of a heart attack or stroke and raising questions about the stability of the succession process.

Given the runaway speculation, the silent approach is “even more reckless than controlling the message,” allowing the rumor mill to turn faster and faster, said Kellee Tsai, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University in the U.S.

China’s top leaders live and work in isolation and only release information about leading personnel that has been carefully molded for positive effect.

Richard Rigby, a former Australian diplomat and China expert at the Australian National University, said that although the Communist Party has become more sensitive to public opinion on certain issues, such as nationalism and social unrest, “when it comes to the leadership, the old conspiratorial instincts of an underground party come to the fore.”

This tendency toward insularity has long been reinforced by the lack of a free press that might demand answers. But it is now under threat from China’s thriving blog and social media communities, especially the hugely popular Twitter-like service called Weibo.

How the government responds to the new technology will be one of the “defining issues for the new leadership,” said Harvard University China expert Anthony Saich.

So far it has responded in part by routinely blocking searches for Chinese leaders, including Xi.

The leader-in-waiting’s sudden disappearance on the eve of his ascension comes during a year full of unforeseen political developments that had already threatened hopes for a smooth party leadership transition.

In March, one of China’s most charismatic and ambitious politicians, Bo Xilai, fell from power and touched off a dramatic scandal that led to his wife’s conviction for murdering a British businessman.

Bo’s own case remains unsettled. That may be a sign that the leadership is divided over what to charge him with.

More recently, one of the president’s closest advisers was reassigned amid reports of his son’s death in March in a speeding Ferrari accompanied by two undressed women.

If Xi’s absence is indeed health-related, he would join some of his forebears among the ruling elite who vanished for health reasons with no explanation.

The party barred all discussion about the frequent absences of Politburo Standing Committee member Huang Ju, who died of illness in 2007. And then-Premier Li Peng also disappeared for several weeks in 1993 after what was believed to have been a heart attack.

Health issues are especially sensitive among top leaders because of the need for them to appear youthful and energetic. China’s overwhelmingly male leaders continue to dye their hair jet black well into their 70s and beyond, which helps to ward off accusations of frailty or being out of touch.

If Xi’s absence were to linger, it might also disrupt plans for the party congress, where Xi is to succeed Hu as party leader. The dates for the congress, held once every five years, were expected to be announced following a meeting of the 25-member Politburo this month, but it may have to be delayed if Xi remains out of action.

If he is permanently indisposed, it isn’t clear what would happen next, due to the opacity of the party’s functions and its failure to institutionalize the succession process.

Xi was picked five years ago to succeed Hu by an undefined formula. Before that, many observers had pegged Executive Vice Premier Li Keqiang as China’s next president. If Xi were unable to assume power, much attention would probably turn to Li, who is now set to take over from Premier Wen Jiabao as the party’s No. 3 ranking official, with chief responsibility for managing China’s economy, the world’s second-largest.

Yet Minxin Pei, a China politics expert at Claremont McKenna College in California, said Li would not automatically be next in line, at least not right away. A compromise candidate might rise and Li would be forced to wait until the next congress in 2017.

“Another battle would be fought,” Pei said. “With several strong contenders.”