A country’s wealth is measured by how well it can provide for its people’s basic needs like food, clothing, shelter. Money makes acquiring these three necessities possible.

In First World countries like the United States, southern states fill domestic demand and still have excess to export, though a good portion of its genetically modified produce have organic produce advocates in an uproar.

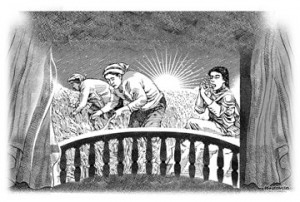

American and European farmers till their lands with tractors and other labor-saving machinery. Compare this with the lowly carabaos and mud-soaked Filipino farmers who consider themselves lucky to own even one hectare of land. This speaks volumes about the country’s state of agriculture in the 21st century.

There are farm-to-market roads but do we have an honest assessment of the amount and quality of assistance given by the national government to the country’s farmers?

As if the country’s dismal agrarian reform program isn’t enough, most of the country’s arable land is owned by big plantations and hacienderos while farmers wait and work for generations to own a few square meters of farmland

(The current Palace occupant, whose family is one of the haciendero elite, handed out the Magsaysay award to Davide as the Philippine’s awardee).

The Jocjoc Bolante fertilizer scam showed that funds intended for assistance were diverted by politicians to non-agriculture lands in order to prop the 2007 election campaign.

The so-called “one percent” of the economic pyramid that owns landholdings is at the heart of this age-old problem of poverty among farmers .

One may reasonably compare the country’s situation with that of Japan, whose economy was in shambles after the bombing of Hiroshima concluded World War II.

One of the first things the Japanese government did in its reconstruction program was to seize the lands owned by the old shogunate, Japan’s ruling class, in order to maximize food production capability.

US author Jack Seward, who is considered an authority on Japan, noted that with the exception of a stubborn few, the shogunate was only too happy to give up their lands to the government because they saw this as a matter of national survival.

Unfortunately the Philippine’s “one percent” doesn’t see things that way and prefers to keep the old, oppressive status quo.

Until this insistence on privileged status is revoked and a new mindset is committed to national survival, the country’s farmers have un uphill struggle for a better tomorrow.