Pangalay: Ancient dance heritage of Sulu

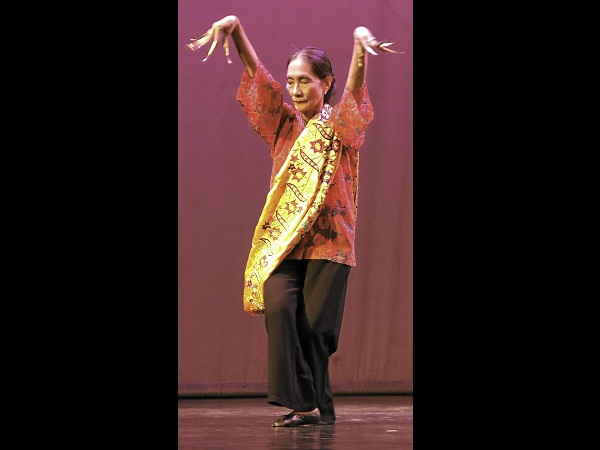

“LINGGISAN” (bird dance) posture and gesture as demonstrated by the author. PHOTO COURTESY OF EARTHIAN MAGAZINE

Modern-day Bongao, the capital of Tawi-Tawi province, has trappings of contemporary living: regular air transport, Internet access, cellular phones, television and various modes of sea and land transportation.

But some four decades ago when I arrived in the Sulu Archipelago, Tawi-Tawi still had no electricity and concrete roads. That’s why amid the flurry of modern living in Bongao at present, scenes from a bygone era haunt my memory: the call to prayer at daybreak from a distant mosque; the tantalizing cadence of “kulintangan” music that wafted unexpectedly anytime from somewhere; the engaging lilt of “lelleng” (extemporaneous ballad) sung passionately after sundown by a neighborhood boy with a captivating voice; the hypnotic sound of “lugo” (chant) earnestly intoned from afar; the lullaby hummed by a solicitous mother to pacify a baby in a makeshift cradle on a house boat or “lepa.”

Time was when the geographically isolated inhabitants of Sulu and Tawi-Tawi satisfy the acute need for a mode of dramatic expression and entertainment through dance. Dancing not only allows them to release kept energy, but also to assert their creativity in a community of strongly held traditions and customs.

Intricate movements

The people in the Sulu Archipelago may have several names for the “pangalay” dance style which has a distinct movement vocabulary. The Badjaw use the generic term “igal” to name the dance which is “paunjalay” among the Yakan of Basilan province.

Article continues after this advertisementThe dance may look quite simple at first glance but upon closer scrutiny, its intricacy becomes obvious. Even more apparent is the similarity of pangalay to other Southeast Asian modes of classical dancing: the Cambodian, Burmese, Thai, Javanese and Balinese. In Sanskrit or the holy language of much of India, pangalay means “temple of dance” or “temple dancing.”

Article continues after this advertisementCaptivated by the beauty of the pangalay, I became passionate in recording and learning it from innumerable dancers in the Sulu Archipelago. In order to preserve the dance, I devised a practical way of remembering postures and gestures, aided by my own silhouette reflected on the wall by a lighted candle.

The habit irritated my husband because even way past bedtime, I would still dance and analyze my silhouettes on the wall and figure out if my shadow matched what was recorded in my mind. This became my routine every time I would see new postures and gestures from new dancers whom I chance upon in serendipitous situations.

My shadow silhouettes became the most reliable learning guide since there was no electricity all over Tawi-Tawi province at the time. Electricity came only in the 1980s.

Instruction method

In the absence of any formal method of instruction, modifications and elaboration by countless pangalay performers are inevitable. Also, owing to the limitless possibilities of improvisation depending upon the performer’s artistry and skill, it would be a mistake to regard a particular variant of the pangalay as the correct or authentic form or style.

To preserve and conserve the abundant pangalay movement vocabulary, a method of instruction has been developed based on more than four decades of experience, study, documentation and performance. This is the Amilbangsa Instruction Method (AIM), which gives equal emphasis on technique and creativity.

The method of instruction is the key to the preservation of intangible cultural heritage like the pangalay. Through the AIM, those who are already dancing the pangalay should be able to distinguish between the good and the bad manners of dancing (the pangalay), and to correct whatever may be aesthetically inferior. Flawed techniques that may even cause injury can be avoided, and the standard of pangalay training may be elevated.

Lastly, the AIM training program is designed for all ages, for amateurs, for dancers in other disciplines, for native pangalay dancers interested to learn effective rehearsal techniques, in order to enrich their vocabulary of traditional movements already half-forgotten.

The story of how I codified two dances, the “linggisan” and the “igal kabkab,” demonstrates the painstaking process of preserving and conserving traditional dance.

Working on ‘linggisan’

To amplify hand movements, the use of “janggay” or metal claws is popular in the Sulu Archipelago. The janggay magnifies the intricate hand movements in linggisan (bird dance).

My first glimpse of linggisan was in Jolo, Sulu, in 1969. Gay dancers performed the “dallingdalling” at Plaza Tulay on Sundays after supper. The comic song-dance has a serious portion about a bird. This is the linggisan.

I was impressed upon seeing the sophistication and richness of its postures and gestures. When danced as a solo number, the Samal and Tausug used kulintangan accompaniment with a distinct melodic pattern. The most impressive rendition of linggisan that I witnessed in Jolo was danced by a woman whose gestures were exceptionally beautiful.

When I arrived in Bongao in 1973, I often saw students and ordinary people dancing some linggisan movements during school programs and celebratory gatherings. Learning the linggisan vocabulary involved serious memory work. Thanks to my reliable candle-and-shadow method, I pieced together postures and gestures from numerous dancers through more than two decades of research and experience in the Sulu Archipelago.

This was the long and tedious process of how I created the cohesive movement vocabulary specific to linggisan alone, which I codified in stick figures, and later were superseded by my own silhouette figures that first appeared in my book titled “Pangalay,” published in 1983.

To date, my linggisan choreography is the most complex version that is a complete dance in itself—with a beginning, middle and ending—that combines complex postures and gestures distilled from observing many native dancers.

Original choreography

The fan is a favorite prop in Asian dance. However, the igal kabkab (literally, fan dance) is not popular among native dancers who obviously did not treat it as a serious dance, but only for merriment.

I was excited the first time I saw a dancer use the fan in dancing basic pangalay movements in 1973. This proved to be a rare encounter because it took another three years, in 1976, before I chanced upon another dancer who performed the pangalay with a fan, at a moonlight picnic or “lamburuk” by the beach on Sibutu Island.

Imagining the beauty of pangalay movements with the use of a fan, I created my original choreography of igal kabkab in 1993—a far cry from the simple fan dance I witnessed in 1973 and 1976—by fusing more complex pangalay postures and gestures which I codified.

I was inspired to develop the simple fan dance for a global audience: My choreography of igal kabkab was intended for the International Dance Festival in Seoul, South Korea, sponsored by big media institutions like KBS and Chungang Daily newspaper, and the Korean Culture and Arts Foundation.

For that occasion, I used the beautiful fan given to me as a present by the president of Asian Dance Association, Madam Oh Hwa-jin, during the Asian Dance Festival held in conjunction with the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

This original igal kabkab choreography is now part of the repertoire of the dance groups which I co-established, namely Tambuli Cultural Troupe and AlunAlun Dance Circle. Hopefully, igal kabkab will gain more prominence in the Sulu Archipelago to demonstrate the rich possibilities of transforming a simple dance without sacrificing the authentic character of pangalay.

Preservation

The preservation of the movement vocabulary of an intangible cultural heritage like the pangalay is of primary importance. But conservation in aid of preservation is equally important. For example, for popular appeal and contemporary context, we may use different kinds of music in pangalay choreography but without losing the intrinsic character of the dance.

Whatever type of music is used—whether pop, rock, folk, western classical or novelty—dancers must consistently maintain the pangalay posture, and its slow, smooth, meditative and flowing movements. Motion in stillness, stillness in motiom—this is the wellspring of the refined and elegant qualities of the pangalay dance tradition.

—————–

Editor’s Note: Ligaya Fernando-Amilbangsa lived in Sulu and Tawi-Tawi for several decades. Her husband is Datu Punjungan Amilbangsa, a younger brother of the last reigning sultan of Sulu—Sultan Mohd. Amirul Ombra Amilbangsa. Starting in 1969, she has undertaken exhaustive field research and documentation of the local culture in the Sulu Archipelago, specifically pertaining to the performing and visual arts of the Samal, Badjaw, Jama Mapun and Tausug. The wealth of primary data that she gathered is published in two volumes: “Pangalay: Traditional Dances and Related Folk Artistic Expressions” (1983), which was given the National Award for Best Art Book by Manila Critics Circle; and “Ukkil-Visual Arts of the Sulu Archipelago” (2005), which was awarded as one of the best publications in the Philippines in 2006.

She was bestowed the honor of being the First Most Outstanding Artist of Tawi-Tawi, presented by Gov. Sadikul Adalla Sahali in September 2011 during the 38th foundation anniversary of Tawi-Tawi province.