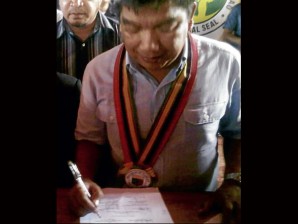

MUJIV Hataman affixes his signature on the pact. FILE PHOTO/JULIE ALIPALA

COTABATO CITY, Philippines—Unlike their national counterparts, who can’t seem to live without it, lawmakers in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao have eschewed pork barrel in passing the region’s Public Works Act, also known as Muslim Mindanao Act 229.

The piece of legislation is actually the second regional law the legislators passed barely two months following their appointment as members of the regional legislature by President Benigno Aquino III. The other law is the ARMM Human rights Act.

ARMM Acting Governor Mujiv Hataman signed both measures into law when he met with all 24 members of the Regional Legislative Assembly on Tuesday.

Last year, Congress passed a law scrapping ARMM regional elections that were scheduled for last August and giving President Aquino the power to appoint regional officials to hold office until the next regional elections, which will be synchronized with mid-term national elections in 2013. He appointed Hataman ARMM governor in December and the 24 regional assembly members last May.

The new ARMM Public Works Act scrapped the so-called “district impact funds” or DIP, the local equivalent of the Philippine Congress’ Priority Development Fund or pork barrel, which were used to fund politicians’ pet projects and were widely believed to be a source of corruption.

The DIP provision in the annually passed regional public works law had been adopted by all past ARMM administrations since 1993, Hataman said.

Instead of the regional lawmakers determining their districts’ priority projects, infrastructure programs and projects are now based on the assessment and evaluation made by the ARMM public works department, local civil society organizations and people’s organizations as well as the local government units, Hataman said.

“The bidding process will be made open to the public, with representative observers from the CSOs (civil society organizations) and the media. We will also determine if some local government units are capable of implementing their own infrastructure projects on a localized bidding process, or by administration, if they have the necessary equipment, or with the help of the Army Engineering Battalion in some cases,” said Hataman.

MMA 229 provides for the utilization of P2 billion infrastructure fund program that the national government annually transfers to the ARMM, as required under Republic Act 9054, the Expanded Autonomy Act which serves as the region’s charter.

ARMM Human Rights Act or MMA 228 was passed primarily to “uphold and enhance respect for the primacy of human rights” in the strife-torn region. It is the basis for the newly created ARMM Human Rights Commission.

Hataman said establishing an independent human rights body in the ARMM was long overdue in light of the region’s experience during the martial law period and the long years of Moro insurgency.

According to Lanao del Sur Assemblyman Zia-ul Haq Adiong, principal author of MMA 228, the regional law affirms national and international laws, including the Article III of the Philippine Constitution; Republic Act 9745, the “Anti-Torture Act of 2009”; Republic Act 9851, the “Philippine Act On Crimes Against International Humanitarian Law, Genocide, and Other Crimes Against Humanity”; Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1976); Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984); Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (1979); Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989); and all other international instruments on human rights to which the Philippines is a signatory.

Regional Legislative Assembly Speaker Rasol Mitmug Jr. said MMA 228 becomes the country’s first operational charter of an independent human rights body that is passed into law by a legislative body. The charter of the national government’s Commission on Human Rights is created by an Executive Order, issued in 1986 by then President Corazon C. Aquino.