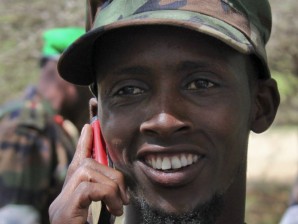

In this photo taken Thursday, June 7, 2012, Abshir Ali Mohamed, a defector from the Somali militant group al-Shabab who is now fighting with Somali government forces alongside the African Union (AU) peacekeeping force, receives a call from his former al-Shabab commander Sheik Mustaf, while speaking to the media at the AU base in Elasha Biyaha on the outskirts of Mogadishu, Somalia Thursday, June 7, 2012. Somali military and government leaders say Mohamed's defection is an example of a trend growing in their favor, with the East African country's most notorious militant group losing manpower and ground. (AP Photo/Jason Straziuso)

ELASHA BIYAHA, Somalia — Evil laughter pealed out of the mobile phone. Abshir Ali Mohamed, an al-Shabab defector now wearing a Somali military uniform, had asked his former commander to join him. The commander, an al-Shabab judge known for ordering amputations, said he would instead kill Mohamed.

Somali military and government leaders say Mohamed’s defection is an example of a trend growing in their favor, with the East African country’s most notorious militant group losing manpower and ground. The 24-year-old former insurgent left al-Shabab less than two weeks ago and now wears a bright blue patch with a white star — the Somali flag — on the shoulder of his government uniform.

“Al-Shabab is no longer. It’s going to end soon,” Mohamed said last week at freshly dug Ugandan-Somali military base on the outskirts of Mogadishu. The base was set up after African Union troops kicked militants out of the towns of Elasha Biyaha and Afgoye.

“Al-Shabab is changing sides because of heavy losses. Those who still fight with them are running away in small groups. They’ve lost weapons. They’ve lost personnel,” he continued. More are looking to flee, he said.

Somali government spokesman Abdirahman Omar Osman said Thursday that some 500 al-Shabab fighters have defected to the government side.

“The defections have been increasing day by day since our forces captured Afgoye town. That put huge pressure on them,” Osman said.

The spokesman for the African Union military force said AU commanders are seeing more defections than ever.

“It’s a sign al-Shabab is losing cohesion, losing command and control,” Lt. Col. Paddy Ankunda said.

Col. Kayanja Muhanga is the Ugandan commander in charge of Battle Group 8, the fighting force that cleared al-Shabab out of Afgoye. He estimates his troops killed more than 60 insurgents during the three days of fighting last month, a battle that extended the African Union fighting force’s reach outside of Mogadishu for the first time since their 2007 deployment to Mogadishu.

A commander in that battle, Burundian Lt. Col. Gregory Ndikumazambo, said al-Shabab fights courageously.

“They fight but they’re badly organized,” he said.

The strength of al-Shabab is not precisely known. Mohamed — a four-year veteran of al-Shabab until this month’s defection — estimated that the insurgents have 7,000 to 8,000 fighters. Ankunda put the figure at 4,000 to 6,000. The African Union now has a U.N. mandate to field a force of about 17,000 troops across Somalia.

Many of al-Shabab’s troops are reported to have fled into northern Somalia over the last year following their pullout from Mogadishu last August. Fighters are also flocking to Kismayo, the last major city al-Shabab controls. Ankunda said foreign fighters including American, British and Ugandans who fight with al-Shabab and its affiliated al-Qaida arm, have fled to Kismayo in recent days.

Kismayo’s Indian Ocean port is al-Shabab’s last major moneymaker. The militants levy taxes on incoming goods, much as they did at Mogadishu’s largest market until losing control of it last year. The loss of Bakara market cost al-Shabab millions of dollars in annual revenue, Ankunda said, one reason they cannot afford to lose Kismayo.

Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga promised this week that Kenyan troops would take control of Kismayo by August.

“The information we have is that the Shabab will try to defend Kismayo. The information we have is indeed that they are preparing for a fight,” Ankunda said.

Mohamed’s former al-Shabab commander, Sheik Mustaf, called the defector last week just as Mohamed was speaking with a few reporters. He put the call on speakerphone as an interpreter translated the conversation.

Mustaf commands 200 to 300 men in southern Somalia, Mohamed said, and was known as a cruel and feared al-Shabab “judge.” If a suspect was taken before Mustaf, the judgment was typically the amputation of an arm, Mohamed said.

“Why don’t you return to Allah,” Mustaf asked Mohamed during the phone call. Mohamed responded that one day he would welcome his former commander to the government side. Mustaf met that prediction with deep laughter, and told his former fighter he would kill him with his own hands the next time they met.

Standing with Mohamed was a second al-Shabab defector, Mohamed Abdi Abdullahi. The 45-year-old said he left al-Shabab two months ago in response to the militant group’s decision to formally join al-Qaida.

Abdullahi, who has earned a living as a gunman most of his adult life, said he wants peace so that his five children can go to school and have access to health care.

“Everybody is tired of war,” he said.

Somalia has not seen peace since 1991, when clan-based warlords toppled dictator Mohamed Siad Barre and then turned on each other. The rise of Islamist militants over the last decade fueled even more fighting.

___

Associated Press reporter Abdi Guled in Mogadishu, Somalia, contributed to this report.