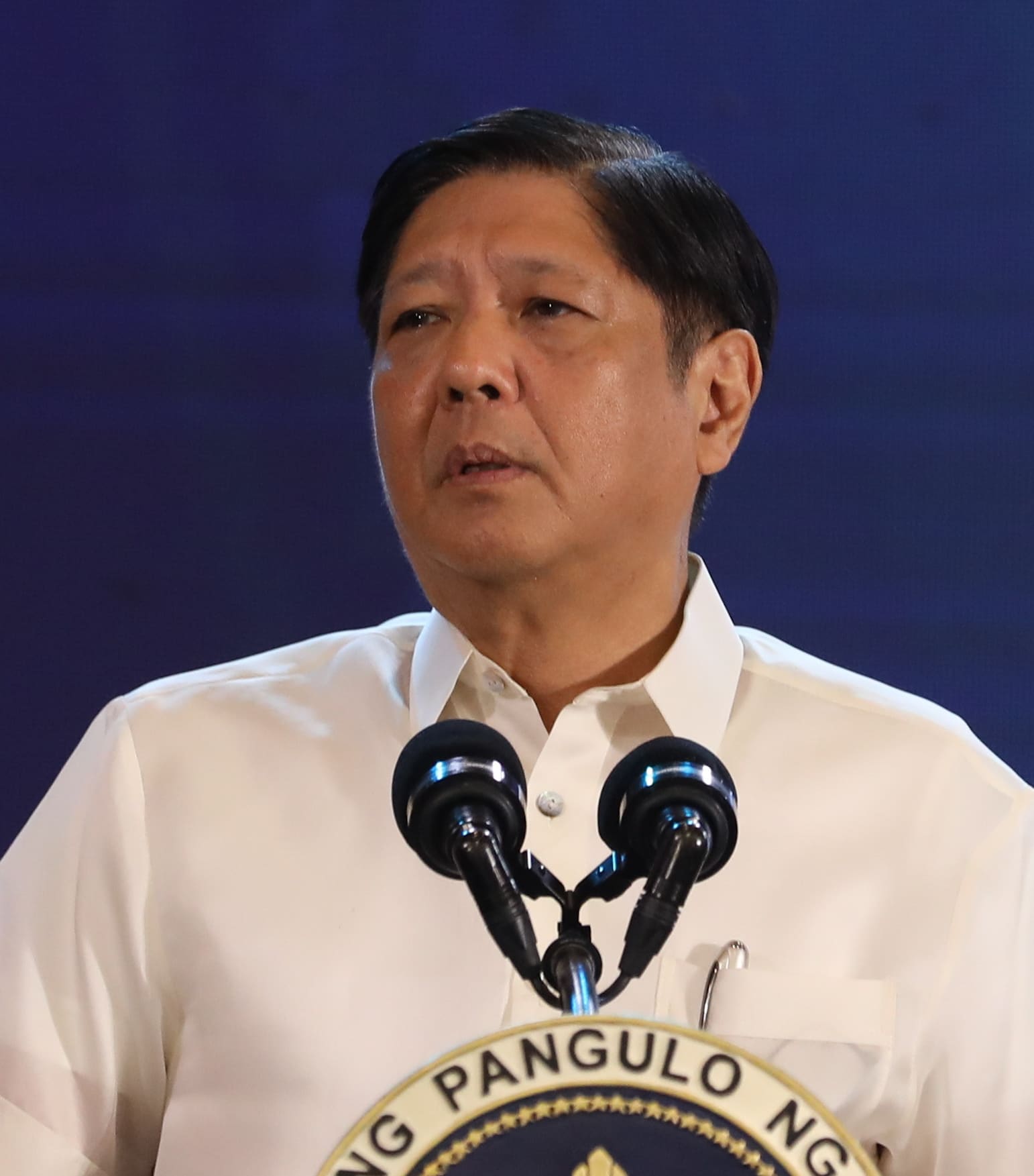

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. —PNA PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines — President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. on Thursday said he and his key Cabinet officials were meticulously scrutinizing the proposed 2025 national budget “item by item, line by line” for “insertions” that were not part of the administration’s original proposal to Congress.

In an interview at Villamor Air Base in Pasay City, the President said the General Appropriations Bill (GAB) passed by Congress vastly differed from the National Expenditure Program that they submitted in July.

“There were a lot of changes from the budget request of the different departments and we have to put it back in the same shape that we had first requested,” Marcos said.

Referring to his meeting on Wednesday with Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin, Finance Secretary Ralph Recto, Budget Secretary Amenah Pangandaman, Public Works Secretary Manuel Bonoan and Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, the President said they were going through the proposed budget “item by item, line by line, to see what is priority and what is not.”

Marcos said he wanted to be “very, very sure” that next year’s spending plan would be directed for very important projects and that there would be “stronger safeguards” on spending for the various projects.

Initial detections

He said his Cabinet members already saw “insertions” of some projects that were not part of the original budget proposal. He said he would be seeking clarification on these projects.

“So, what are these projects? Do we really need them? If we don’t need them now, maybe we can defer it,” Marcos said, without specifying the items that were inserted.

“We are starting to see some project proposals that do not have the appropriate program of work or do not have appropriate documentation. It’s not clear where the money will be spent. So that’s what we’re trying to clarify,” he added.

The President, however, dismissed the possibility of returning the GAB to the bicameral conference committee for another round of fine-tuning of the appropriations and said that he was only left with his power to veto line items or provisions.

“There is no procedure to return it to the bicam. It’s finished already in the House … It’s finished in Congress,” he said. “So, it’s now up to us to look at the items and to see what are appropriate, what are relevant, and what are the priorities.”

“So, unfortunately, I am only left now with the veto power. Because the bicam, the House, the Senate already approved it. Now it’s up to us on how we regain control of the spending program.”

Deferred signing

The Chief Executive made the remarks a day after Bersamin said the scheduled signing of the P6.352 trillion national budget for 2025 on Friday, Dec. 20, will not push through “to allow more time for a rigorous and exhaustive review.”

The Executive Secretary said that Marcos would veto certain items and provisions “in the interest of public welfare, to conform with the fiscal program, and in compliance with laws.”

The final version of the proposed national budget for next year featured massive cuts on several public services, such as P86 billion from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), P74.5 billion from the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), and P12 billion from the Department of Education (DepEd).

Akap, DPWH gains

Critics slammed the P26-billion fund for the Ayuda Para sa Kapos ang Kita (Akap) program and the additional P289 billion for the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), which gave the agency a whopping P1.1-trillion budget for 2025.

The 1987 Constitution authorizes the President to exercise line-item veto powers of an appropriation, revenue, or tariff bill—but Congress may reconsider the veto by a vote of two-thirds of all its members.

On Monday, the President said the government was working to restore the DepEd’s P12-billion slashed funds while taking a harder look at the DPWH’s bloated P1.1-trillion budget for next year.

Marcos said he was fine with the zero subsidy for nonpaying PhilHealth members, as the state health insurer had an estimated P709 billion in reserve funds to continue implementing its universal healthcare program.

He said that the government did not have a large budget or savings to work with in the first place.

“So, we have to be very careful on what we spend it on, especially that the budget also includes loans that we took out. It should be spent for the right things, so we can pay our loans and we can make a little profit,” he added.

The President declined to give a date for enacting the budget as the scrutiny would “take as long as it would take,” but he was optimistic about signing it “before the New Year.”

What Marcos can’t do

Despite his intention to correct some of the appropriations and the funding cuts in the proposed budget, the President cannot reinstate any of the lost allocations or create new ones using his veto power, according to former Finance Undersecretary Cielo Magno, a critic of the Akap dole-out program.

In the case of the zero subsidy approved by the bicameral committee for PhilHealth, “a veto of that provision will not allow the President to add the missing appropriation,” Magno told the Inquirer.

“In the same vein, deductions made by Congress on the budgets of various government agencies cannot be restored by a veto,” she said.

“The President, in exercising his or her veto power, does not have the power to appropriate money for specific government uses,” said Magno, an associate professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.

What the President can only do should he decide to use his veto power is to remove parts of the proposed budget, Magno pointed out.

Marcos also does not have the “power to make appropriations he believes are consistent with the Constitution,” she said.

Under Article VI, Sec. 27, of the 1987 Constitution, the President may veto “any particular item or items” in the budget bill without affecting other provisions he does not object to.

Earlier conflict

The President has to inform Congress of his veto within 30 days after receiving the budget bill, or else the entire budget proposal would lapse into law.

The vetoed provisions would then have to be deliberated again and approved by at least two-thirds of the members of Congress.

In 2018, a conflict occurred between the executive and the legislature over the national spending program when then Camarines Sur Rep. Rolando Andaya, Jr. accused President Rodrigo Duterte of restoring some P75 billion in allocations to the DPWH when he approved the 2019 budget with vetoed provisions.

READ: Senate OKs P6.352 trillion national budget for 2025

Benjamin Diokno, who was the budget chief at the time, responded, saying that this was an “unnecessary speculation.”

“Congress has done [its] job. They should let [the executive] do ours. If they are not happy with the President’s veto message, they may still override it through a vote. That is the essence of checks and balances,” Diokno said in a statement.

He also stressed that the President can only veto a specific line item, but “cannot introduce or bring back items that have already been deleted by Congress.”