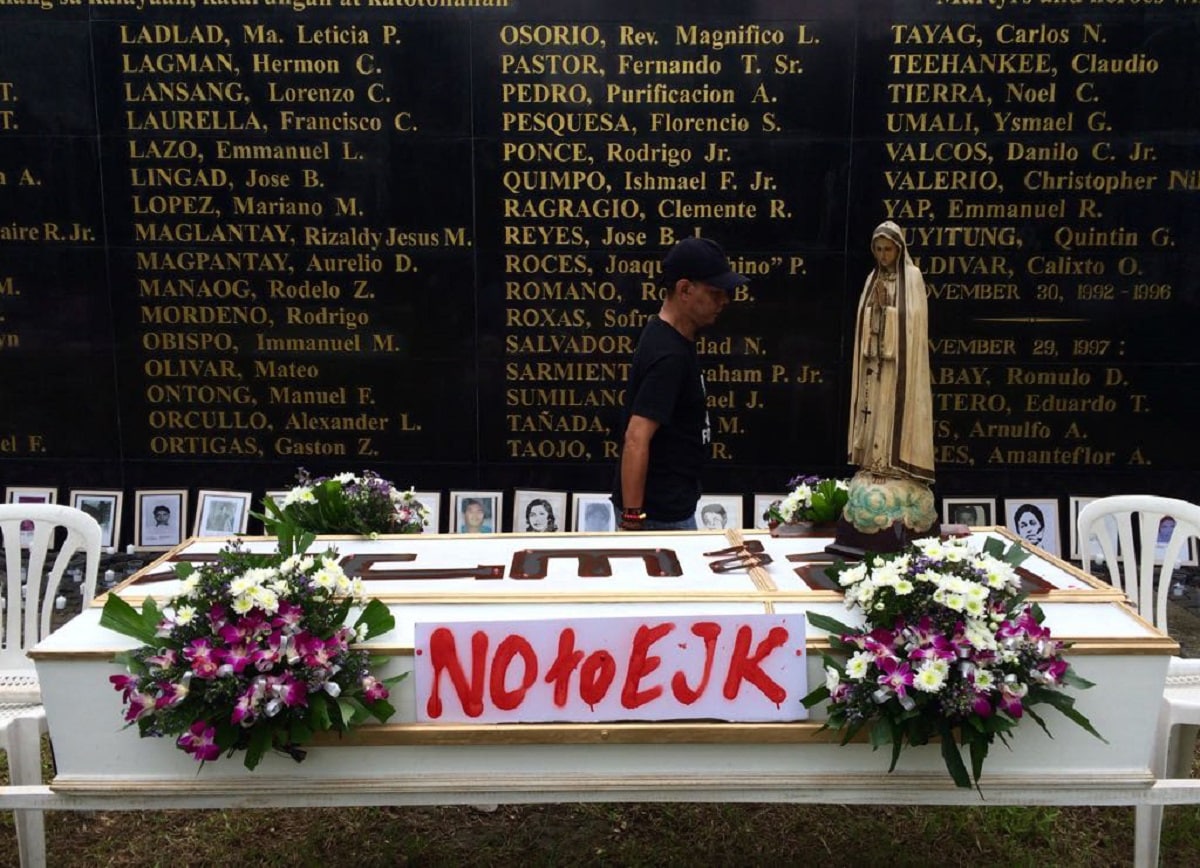

2 DEATH TOLLS The phrase “extrajudicial killings” has been applied both to the victims of the Duterte drug war and those of politically motivated attacks, some of them memorialized here at Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City. —Lyn Rillon

MANILA, Philippines — As the House of Representatives began tackling a measure seeking to criminalize extrajudicial killings (EJKs) in light of the thousands killed during the drug war, the lawmakers immediately ran into a quandary: What exactly are EJKs?

During Wednesday’s hearing called by the House committee on justice—its first hearing on House Bill No. 10986 seeking to penalize EJK as a heinous crime—lawmakers, civil society representatives, and law enforcement agencies struggled to define what an EJK was and how it differed from murder and homicide.

READ: DOJ creates task force to probe EJKs, file cases

The bill, authored by ranking House leaders, was one of the measures that came out of the House quad committee’s monthslong inquiry into crimes related to the drug war and offshore gaming.

Hard to litigate

The authors sought to address a longstanding concern of rights groups: that EJKs are not completely understood and therefore difficult to litigate and prosecute.

It’s why most of the police officers who have killed drug suspects during operations were charged with murder or homicide and not the crime of EJK, one of the bill’s authors and Lanao del Sur Rep. Zia Alonto Adiong pointed out.

“That’s why … the language (of this bill) should be very, very specific because that’s how courts decide. How do we say something is an EJK or a murder? There seems to be a very thin line between the two,” Adiong said.

State solicitor Rose Celine Europa, who represented the Office of the Solicitor General, told lawmakers that there was already a definition of EJK enshrined in Section 5(l) of Republic Act No. 11188, which provides special protection of children during armed conflict.

That law defines EJK as “all acts and omissions of State actors that constitute a violation of the general recognition of the right to life embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the UN Convention on the Rights of Children and similar other human rights treaties to which the Philippines is a State party.”

‘Too vague’

This is almost verbatim of the United Nations’ own definition of an EJK, which is used to guide international law.

Beyond that, said State Solicitor Jennifer Siron, “from what we gathered from court decisions, extrajudicial killings are acts committed by public officers which are not really authorized by the state … (simply put), it cannot be called extrajudicial killings if it is not committed by public officers.”

She admitted that the definition under RA 11188 was “too vague” for the proposed law against EJKs.

Muntinlupa Rep. Jaime Fresnedi challenged the definition, as there could be killers who had been hired by public officers but were not public officers themselves.

“I believe that this is a government-sanctioned illegal killing, but not necessarily all actors are public officers,” he said.

‘Imprint of the state’

Karapatan secretary general Cristina Palabay stressed that what differentiates EJK from murder was the “imprint of the state.”

“Meaning to say, it was done by state actors with authorization, support, or acquiescence of those in public positions,” she said.

Navy Capt. Anthony Cabarteja, the chief of the advocacy and research branch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, expressed concerns that such a definition might mean that if a public official committed a killing in their official capacity, “it might be considered an EJK.”

This echoed the defense of most police officers that they had only killed suspects in the line of duty.

Manila Rep. Bienvenido Abante, however, clarified that it could only be an EJK “if he did it [based on] an illegal order, a policy that is against the Constitution.”

The panel chair, Negros Occidental Rep. Juliet Marie de Leon, suggested that the measure could make the circumstances present in an EJK—that is, if it was “sanctioned by a public officer, person, authority, agent, or any person who is acting under the actual or apparent authority of the state”—an aggravating circumstance to murder.

Under the Revised Penal Code, the main difference between murder and homicide is the circumstances surrounding the killing. A killing is a murder if it occurs under certain qualifying circumstances, such as treachery, premeditation, or cruelty, and is punishable by reclusion perpetua (20 years to 40 years).

Homicide also entails killing, but without the qualifying circumstances that elevate it to murder. Its penalty is reclusion temporal, or 12 years to 20 years.

Superior as principal

Under the bill, the penalty for EJK would also be reclusion perpetua. A superior officer who issues an order to a subordinate to commit an EJK will be equally liable as a principal. The bill establishes a claims board under the Department of Justice to provide reparations for EJK victims.

While pressure to define EJKs mounted during the Duterte administration, initial calls to do so started under the Arroyo administration, when UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Execution Philip Alston published a report saying that the AFP killed left-wing activists and human rights defenders as part of a brutal counterterrorism strategy.

The committee will resume its hearings before Congress adjourns before the midterm polls in May.