FAMILIAR TOPIC Facing the House quad committee on Tuesday, former Sen. Leila de Lima revisits a subject dating back to her days as human rights commission chair and for which she earned the wrath of then President Rodrigo Duterte: the so-called Davao Death Squad, the alleged liquidation force who took orders from Duterte when he was still Davao City mayor. —Niño Jesus Orbeta

MANILA, Philippines — The joint congressional panel investigating the war on drugs waged by former President Rodrigo Duterte heard the testimony of former Sen. Leila de Lima, one of the first public officials to question its methods since he first laid down its “template” as mayor of Davao City.

Facing the House quad committee on Tuesday, De Lima corroborated earlier accounts about the so-called Davao template, a phrase used by Royina Garma, a retired police colonel who claimed she was personally asked by Duterte to help implement the scheme on a national scale after he became President.

De Lima was the most prominent figure to appear so far before the four-panel body—and one said to have suffered the consequences of confronting Duterte over the merciless crackdown.

READ: De Lima: Nanlaban, reward concepts started in Davao even before 2016

Despite being an incumbent senator in 2017, she was charged and detained on charges of drug trafficking filed by the Department of Justice, an agency she also once headed, during the Duterte administration.

She was detained at Camp Crame as the trial dragged on for more than seven years. All three cases were eventually dismissed, the last in June this year.

De Lima is currently running for a House party list seat and has earlier spoken of plans to sue Duterte over her legal ordeals.

Duterte, 79, was invited to Tuesday’s hearing but did not show up. According to a letter he sent to the panel, he had to decline for health reasons.

“I attend this hearing with a deep sense of irony,” De Lima said in her opening statement. “I have not forgotten that in September and October 2016, the House committee on justice conducted [an] inquiry on the Bilibid drug trade. However, unlike this hearing, the real subject of that hearing was not in any way about the drug trade.”

“The real subject of that 2016 House committee hearing was all about destroying me for conducting a Senate inquiry which, in so many aspects, was like this one. The only difference between this hearing and that Senate hearing is that my committee inquiry was eight years earlier and Duterte was at the peak of power.’’

“It is so saddening that it was only now that there has been a comprehensive discussion by Congress of the drug war and EJKs, only after the bodies of thousands of victims have already mounted,’’ she said.

First look at DDS

In the course of the hearing, De Lima confirmed several aspects of Garma’s testimony, including how Duterte tapped his most trusted police officers to head major commands, their use of lists obtained from village or barangay governments to select “victims,” and the payoff system for hired gunmen and their “handlers.”

As then chair of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), De Lima launched an investigation in 2009 into the summary killings allegedly perpetrated by the so-called Davao Death Squad (DDS), incurring the ire of then-city mayor Duterte.

The CHR probe, De Lima recalled, found that the DDS was composed of former communist rebels who were hired as hitmen, with active police officers serving as their handlers.

Between 1988 and 2000, the DDS teams were paid P15,000 per kill, split into P10,000 for the gunman and P5,000 for the handler, she added.

At the time, De Lima said, Duterte “personally gave out the kill orders and the reward money directly to the assassins themselves.”

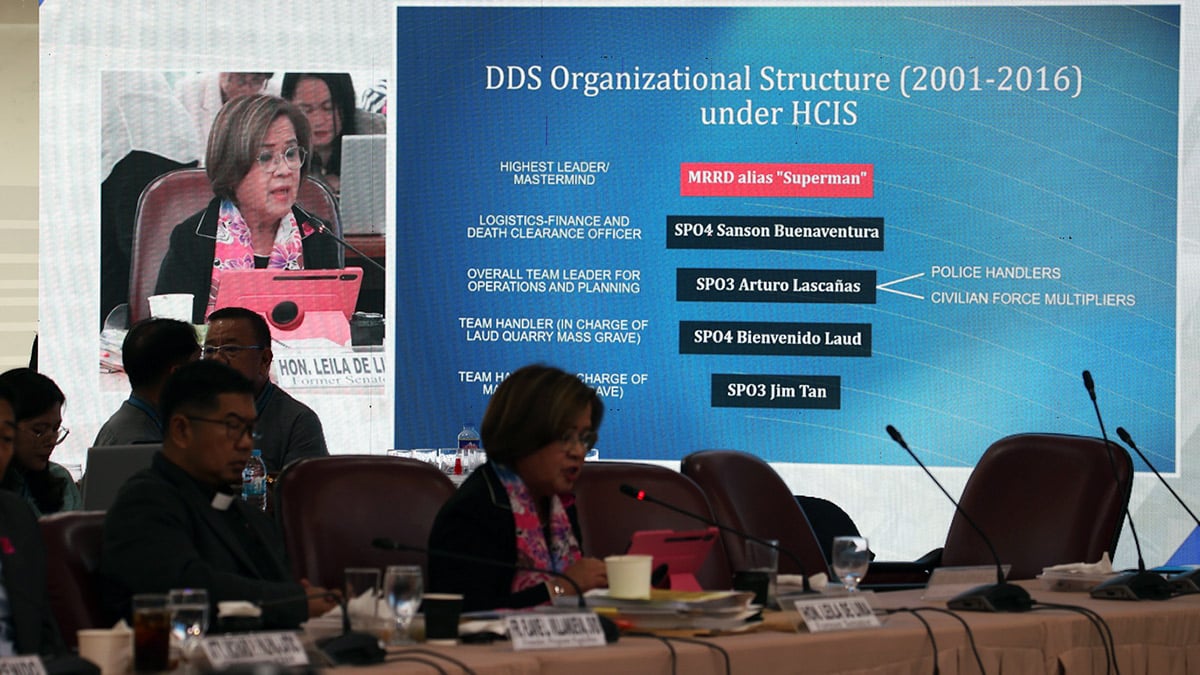

In 2001, she said, the DDS was “upgraded” to make it appear as part of the Davao City police, where it became known in the organization as the Heinous Crimes Investigation Section (HCIS).

By this time, the teams were composed of active officers and civilian “abanteros” or hit men. The reward now ranged between P13,000 and P15,000 per job: P3,000 to P5,000 going to the handlers; P7,000 to P8,000 for the assassins; and P500 to P1,000 for the informants.

“Special projects” that involved high-value targets, De Lima said, were rewarded between P100,000 and P1 million per hit, she added.

‘Nanlaban’ concept

The DDS members “directly received salaries as auxiliary services workers,” the money drawn from the mayor’s intelligence funds, De Lima said in an exchange with Kabataan Rep. Raoul Manuel.

Even the concept of “nanlaban”—or of the suspects being killed because they allegedly resisted arrest and shot back at the law enforcers—came from the DDS operations, De Lima said.

Most of the CHR’s findings were later corroborated by confessed hit men Edgar Matobato and Arturo Lascañas, who went public about the DDS in 2016 and 2020, respectively.

Lascañas’ affidavit on the DDS was later submitted to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is investigating Duterte for crimes against humanity.

De Lima said Lascañas’ accounts would show that the DDS was not just a loosely organized gang but a group that reported directly to Duterte, who was code-named “Superman” in its lingo.

Applicable PH law

These findings, she said, were also part of her personal investigation notes that she submitted to the ICC.

De Lima renewed her calls on the Marcos administration to cooperate with the ICC and reverse the policy it inherited from Duterte.

She also reminded Congress that Republic Act No. 9851, or the law against crimes against humanity, empowers the government to file charges against those most responsible for drug war killings.

The 2009 law punishes the same crimes that fall under ICC jurisdiction, including extrajudicial killings, she said.

Section 6, for example, deals with “crimes against humanity” and the corresponding penalty of reclusion perpetua, while Section 9 specifies the public officials, including heads of state, who can be held accountable.

De Lima further noted that even before the Philippines ratified the Rome Statute, the treaty creating the ICC, in 2011, the country had already recognized the jurisdiction of the tribunal and other international bodies through RA 9851.

The law allows for the surrender or extradition of individuals accused of crimes against humanity to international courts, she said, adding: “It is our own law that says we have to cooperate with the ICC even before we became a member of the ICC. To say that we don’t care about the ICC, we have to repeal this law.”

Should the victims of the drug war decide to file cases using RA 9851 as a basis, it would still depend on the ICC whether it would see it as an improvement of the Philippine justice system, de Lima said.

She was referring to the premise that the ICC investigation only targets persons “most responsible” for the crimes being alleged.

‘Admit your sins’

Asked what she would have told the former president if he appeared at Tuesday’s hearing, De Lima said:

“I’ve proven that I’m beyond (being) threatened by him. Just admit everything. Admit your sins against me, that you merely targeted me, that you invented the cases against me, and that you are the most involved as the mastermind, the one who gave the orders and induced the killings.”

“Admit it so that the victims who have long been seeking out justice can finally have peace,” De Lima said.

In July, De Lima appeared before the House committee on human rights when it conducted its first hearing on the drug war. This was before the creation of the more encompassing quad committee.