MMDA solid waste director Michael Gison discusses the goals of the Metro Manila Flood Management Project Phase-1 to delegates from the World Bank last July 2024. (Photos and videos by Krixia Subingsubing)

The devastating impact of Typhoon Carina (international name: Gaemi) in July, coming just days after President Marcos announced the completion of about 5,500 flood control projects nationwide, prompted angry congressional hearings against the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) after the storm.

In those hearings, Public Works Secretary Manuel Bonoan admitted that the said projects were not part of any integrated master plan but “stand-alone projects [aimed at providing] immediate relief to low-lying areas.”

The agency was struggling to implement the P352-billion Metro Manila flood management master plan which the government approved way back in 2012 and is supposed to finish by 2035.

DPWH project engineer Lydia Aguilar said the master plan was designed “specifically to avoid another “Ondoy-like scenario,” referring to the devastating 2009 storm (international name: Ketsana) that killed over 660.

“Before 2012, the prevailing master plan for Manila was drafted [way back] in 1990. But because of the worsening impacts of climate change, we realized there was a need to update it,” she said.

Bonoan admitted that the master plan was still “below 30 percent completed,” since its full realization depended in large part on the completion of its large-scale infrastructure projects—such as Phase 1 of the $500-billion Metro Manila Flood Management Project (MMFMP).

This initial phase itself has barely made any progress even as its original deadline this November approaches.

No real master plan

Floods remain a part of metropolitan life, even 15 years after Ondoy’s onslaught—as Marikina Rep. Stella Quimbo noted about her flood-prone hometown.

“How can we even think about being an upper-middle income country in 2028 if we can’t even control floods?” she said.

At the start of this 19th Congress, Quimbo filed House Bill No. 492, which would direct the National Economic and Development Authority to review the 2012 master plan and identify targets and needed reforms.

Quimbo said “we have failed to learn from our experience” even after Ondoy. “Long-term reforms have to be instituted now to build a disaster-resilient country… An institutionalized and comprehensive plan, coupled with timely and adequately funded implementation, can realize such an objective.”

Public Works Undersecretary Emil Sadain, however, emphasized that there has never been a unified, comprehensive master plan to deal with flooding in the Philippines.

There are actually 18 separate master plans that the DPWH is supposedly carrying out, one for each major river basin across the country.

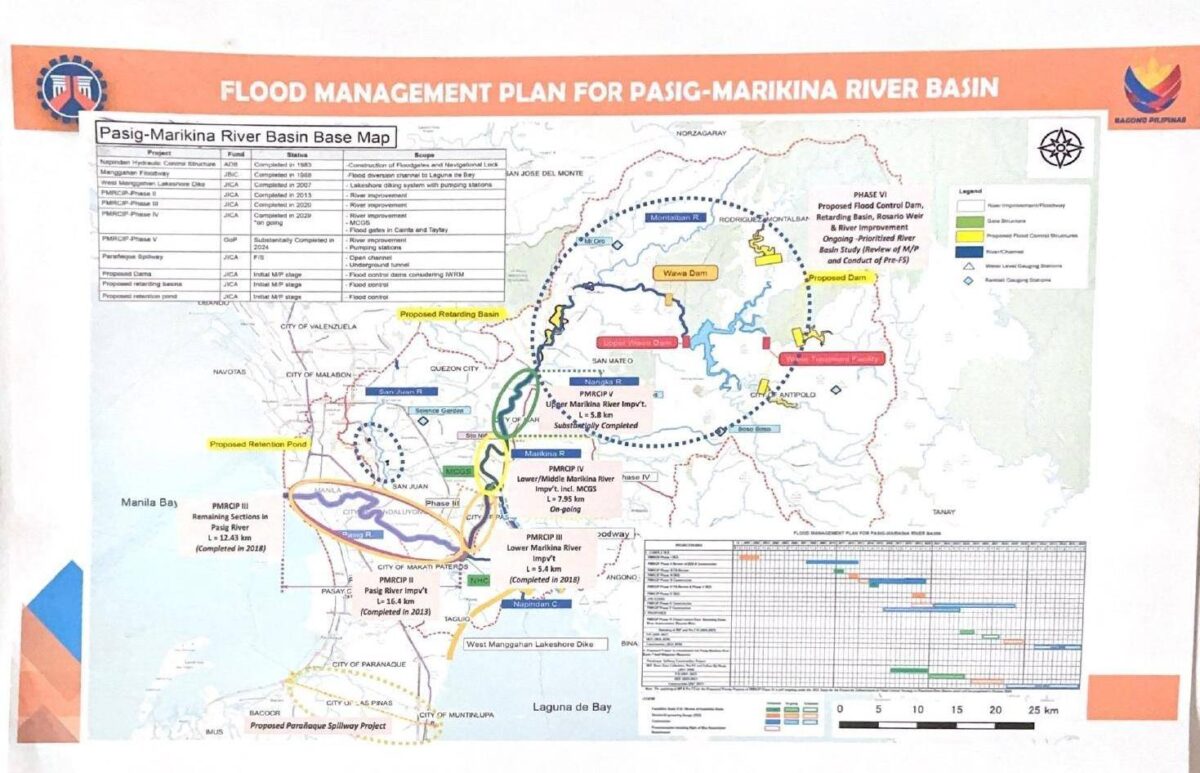

The 2012 master plan for Metro Manila, for instance, specifically focuses on the Pasig-Marikina River Basin, Sadain said.

The basin covers Metro Manila in the west; portions of Bulacan in the northwest, and Rizal, Laguna, Cavite and Batangas in the south.

During heavy rainfall, water estimated at about 2,100 cubic meters goes through the Pasig and Marikina Rivers before it discharges into Laguna Lake.

Public Works Undersecretary Emil Sadain discusses the Flood Management Plan for the Pasig-Marikina River Basin, one of 18 master plans for flooding in the country. (Photos: Krixia Subingsubing, DPWH)

According to the World Bank, the main elements of the Metro Manila master plan include building a high dam in the upper Marikina River catchment area to reduce river flows entering the city during typhoons and extreme rainfall events, as well as structural interventions to eliminate flooding in Laguna de Bay.

A map of the Pasig-Marikina river basin master plan, as designed by the World Bank in 2013. Source: DPWH

‘All interventions’

But the DPWH has asked the Japan International Cooperation Agency to fund a feasibility study on the construction of three dams instead, according to Sadain.

This would have a combined capacity of holding 84 million cubic meters of water and would “significantly lessen the amount of water that has to go through the rivers and therefore lessen flooding,” Sadain said, adding that the agency expects to finish the project by 2031.

The MMFMP also aims to build a spillway in Parañaque that would divert floodwaters from Laguna Lake into Manila Bay during extreme weather as well as improve urban drainage.

That plan, Sadain said, also covers various engineering solutions like building revetments and riverwalls along Pasig River and floodwalls in Marikina River, as well as nonstructural measures like improved flood forecasting and early warning systems.

Indeed, as the World Bank noted: “In order to improve the overall flood management conditions in Metro Manila, all interventions under the above-referenced elements have to be implemented.”

It pointed out further that “each structural element has unique solutions that are not directly linked to other elements and can be implemented independently from each other.”

Reclamation, drainage

But for disaster anthropologist Pamela Cahilig, even the most well-intentioned flood management plans could go awry—especially since the country continues to approach flooding with “one-size-fits-all” solutions, she said.

“The question that’s always asked of me especially after Carina is, ‘How can we reduce flooding in Metro Manila?’ And my answer is always, ‘Which part?’ Because if you’re talking about, say, Pasig, which is close to the river—they get riverine flooding, which means you might need a watershed approach to flood management.”

“If you’re talking about urban areas like Manila [or] Makati, you might want to look at drainage systems. If you’re talking about areas near Manila Bay, you might want to look at reclamation that changes ocean currents and sea beds.”

The solution must fit the specific problem in a given area, said Cahilig, a University of the Philippines-College of Architecture lecturer who specializes in disaster and nature-based flood management.

Yet most flood managers in the country, she noted, would instead—often by instinct—resort to hard engineering solutions like concrete dikes or sea walls to control flooding, regardless of its cause.

Other solutions

“There is an order of flood management solutions that we could actually consider [that would] do as minimal harm as possible,” Cahilig said.

This includes, she said, conserving wetlands and watersheds, which act as natural filters that reduce runoff and prevent flash floods in downstream communities.

Solid waste management is just as important especially in Metro Manila, said Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) Director Michael Gison.

In the case of the MMFMP, for example, it is important that “while we rehabilitated and constructed new pumping stations, we need to educate our barangays to do their part in not throwing garbage willy-nilly,” he said.

At least $47 million of the MMFMP is allotted to projects managed by the MMDA that would help minimize solid waste in waterways. Most of these funds go to the maintenance and operation of the materials recovery facilities (MRFs) in the pumping stations.

MRFs sift through recyclable materials, biowaste and water lilies raked in by the pumps and these would be turned into bricks, hollow blocks and compost, Gison said.

Community involvement

The MMDA also has a “Recyclable Mo, Palit Grocery Ko” program which encourages residents to exchange their recyclables at the MRFs in exchange for points which can be used to “buy” grocery items on MRF Market Days.

These programs are particularly successful in communities near the pumping stations such as Vitas and San Andres in Manila, where women’s groups basically drive demand.

Unlike the other components of the MMFMP, where success is measured by project completion, “the real objective [of the solid waste management aspect] is social behavioral change,” Gison said. “Remember, the loan can only be availed for a limited period of time. After that, it’s up to the local government units and [up] to us to continue what we’ve done.”

This also means government agencies should stop working in isolation from each other.

“If you say that flood management is more than flood control, then that means other than the DPWH, there needs to be the involvement of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources or even the Department of Social Welfare and Development,” Cahilig said.

But most importantly, “involve communities in the conversation,” she said. “People are experts in their own lived experiences of disaster, and it’s really, really important to listen to that.”

This report was written with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the Asian Center for Journalism of Ateneo de Manila University.