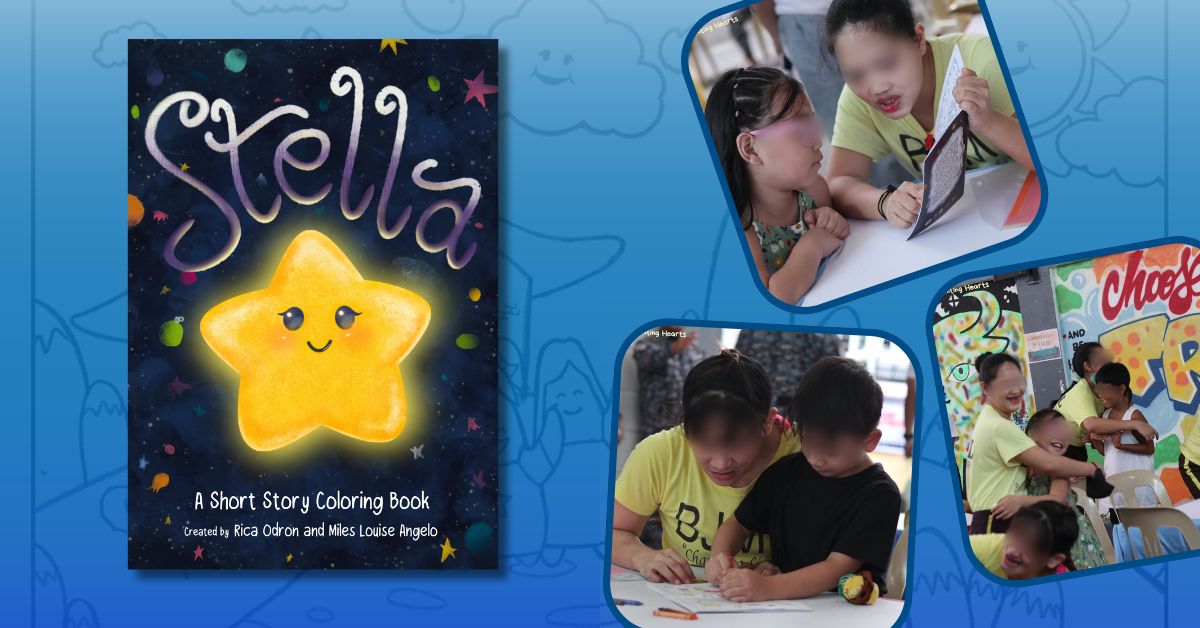

The Humanitarian Legal Assistance Foundation (HLAF) has launched a coloring book project called Stella to help detained moms and their children see the light of hope behind bars. Photos courtesy of HLAF/Facebook. Graphics: Kathy Baugbog/INQUIRER.net trainee

A mother’s love is a color that never fades and a shade that never changes. However, some inevitably suffer the loss of their color due to forces beyond their control.

Persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) face consequences limiting their communication and relationship with their families. For this reason, Stella, a coloring book project, aims to strengthen the bond and relationship of a detained mother and her child through storytelling, coloring, and writing activities.

The book was launched by the non-government organization Humanitarian Legal Assistance Foundation (HLAF). Written and illustrated by Rica Odron and Miles Louise Angelo, the book tells the story of a mother who went missing and later found her way back home.

For HLAF advocacy officer Melvin Nuñez, the Stella project is the “bright side” that supports every PDL mom’s journey toward regaining themselves and returning to the arms of their loved ones.

He shared that the pain of a mother who left her children at a young age and then saw them again only when they got older is one of the reasons for the project.

“Some of them are only accused, and some would be acquitted after years, and that’s the only time they will be able to reunite with their children… They were not able to see the development or the growth of their child,” he said.

The project came into life with the idea of extending the bonding time between the PDLs and their children because the visitation hours only last 10 to 20 minutes.

“Usually the problem there is that when [families] visit, they just eat and talk. They don’t have the time to bond… So [Stella] started only with an idea to support the bond of the mother and her child through a coloring book,” Nuñez said.

“That is an addition to the time they get to spend with their families, which they do not usually get to do during visitations,” he added.

The Stella project lasts two to three hours, giving PDLs enough time to bond and reconnect with their families through activities such as playing parlor games and eating a meal together.

“We really made it possible because [we see] children who long for the presence of their mothers, especially our participants who are usually younger than 12 years old,” Nuñez said.

He also said that the foundation is pushing the Quezon City Jail, one of the primary venues of their projects, to adopt and institutionalize the Stella project as part of its family days.

This year, HLAF has implemented three Stella projects in jails.

‘Coloring hope, reuniting hearts’

A mother reads the story of “Stella” to her daughter. Photo courtesy of HLAF/Facebook

The Stella project has allowed detained mothers to be with their families despite being separated by prison. For them, it is not simply a coloring book event but an experience that they will cherish for their lifetime.

HLAF advocacy associate Mark Angelo Zamora shared an encounter with PDLs who expressed their happiness with the project.

“They were happy because it was their first time bonding with their children, coloring [a book], playing together, and reading them a story,” he said.

It was also the detainees’ first time sharing a meal with their family.

Mothers and their children happily participate in a parlor game as part of the project. Photo courtesy of HLAF/Facebook

Every Stella project offers unique stories and insights. Nuñez said it also seeks to increase the PDLs’ sense of purpose and show them they are not alone in their journeys.

“We can see in their eyes that there is still a sparkle even when they are crying… that there is still hope to live even though they are inside the prison,” he said.

“We saw that they never lose hope because they know that someone is helping them even though they are in prison… They never feel abandoned because they see that they have a companion in their journey,” he added.

Guiding light

Motivated to promote human rights, the foundation’s volunteers said their inspiration to keep their advocacies going is the contributions they were able to offer to PDLs and how they continue to spark their hope despite being imprisoned.

“We believe that all people have hope and that they all need to be given a second chance. We always say that they are just victims of circumstance so we are here to give them a chance to make a change,” Zamora said.

“Even if you only change one life and free one person, it is a huge contribution to the PDL community. This is compelling not only to a single PDL but for their community as a whole because they can see that there is still someone helping them,” Nuñez added.

A child writes her mom a note of love. Photo courtesy of HLAF/Facebook

Nuñez also stressed that the rights of PDLs must be protected as stigma and discrimination continue to envelop the minds of the public.

Under the law, a detainee accused of any crime is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

“The main problem is that they do not have social support when they are incarcerated, especially when they are surrounded by stigma and discrimination. Because when they have been imprisoned, [people tend to assume] that they are already convicted even if they are still not proven guilty,” he said.

Meanwhile, the foundation volunteers encourage the youth to become an avenue to forward human rights and be a beacon of change to the vulnerable.

“They (youth) should not be afraid to engage in human rights organizations because no one will help others if no one volunteers. [It is like the quote:] If not us, who? If not now, when?” Nuñez said.

HLAF also implements long-term programs, such as the Jail Decongestion Program, the Center for Restorative Action, and the Focused Reintegration of Ex-Detainees, which all aim to promote the rights, welfare, and well-being of detainees. — Rachelle Anne Mirasol, INQUIRER.net trainee