‘Uswag’ and his last flight

READY FOR RELEASE Philippine eagle “Uswag” is photographed while inside his cage at the Philippine Eagle Center in Davao City before he is taken to Burauen, Leyte, on June 11 in preparation for his release. —Photo courtesy of the Philippine Eagle Foundation

BAYBAY CITY, LEYTE, Philippines — Conservationists are puzzling over the drowning of a Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) off the coast of this city on July 30, especially about how the raptor, which is supposedly a territorial forest-dweller, ended up in the sea.

“This phenomenon has puzzled us for many years now,” said Dennis Salvador, executive director of the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF) which partnered with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to reintroduce the raptors in Leyte province.

READ: PH eagle ‘Uswag’ drowns off Cebu after straying from Leyte forests

The program was hatched after eagle nesting sites were wiped out by Supertyphoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 2013, the world’s fiercest storm. As the top forest predator, or apex predator in the food chain, the raptors help keep balance in the ecosystem where they belong.

A pair of juvenile raptors rescued from wildlife poachers in Mindanao were chosen to be translocated into the forests of Leyte. After their complete recovery, 3-year-old male “Uswag,” and 6-year-old female “Carlito” were flown from their rehab cages at Philippine Eagle Center in Malagos, Davao City, on June 11 and underwent acclimatization before their release on June 28 in the Marabong watershed in Kagbana village of Burauen town.

Article continues after this advertisementDr. Jayson Ibañez, PEF operations director, Uswag and Carlito were chosen because as immature birds, considered “surplus birds,” they did not yet have a territory and hence could look forward to building their own in Leyte.

Article continues after this advertisementDays after their release, the pair was seen by forest guards in the area being mobbed by hornbills during several occasions, although they seemed to have managed well in their new environment. Uswag was also monitored to have been actively hunting for food.

But after its last monitored location at the edge of the forests on July 9, the solar-powered transmitter fitted on Uswag’s body sent coordinates that suggested he was already at sea by July 30.

The spot was almost 6 kilometers away from its July 9 location, and 102 km away from the village of Kagbana where he was released with Carlito.

Uswag’s location after he crashed into the sea off Baybay City in Leyte on July 30.

Sea is risky

Philippine eagles, Ibañez said, should not be at sea for three reasons.

First, they are strictly forest-dwelling. “It is designed by nature to live only inside the forest,” he explained.

Second, fish are not their food. “Osprey, other eagles, like the white-bellied sea eagle, gray-headed fishing eagle and brahminy kite, eat fish. Philippine eagles only eat mammals, birds, big lizards and snakes,” he said.

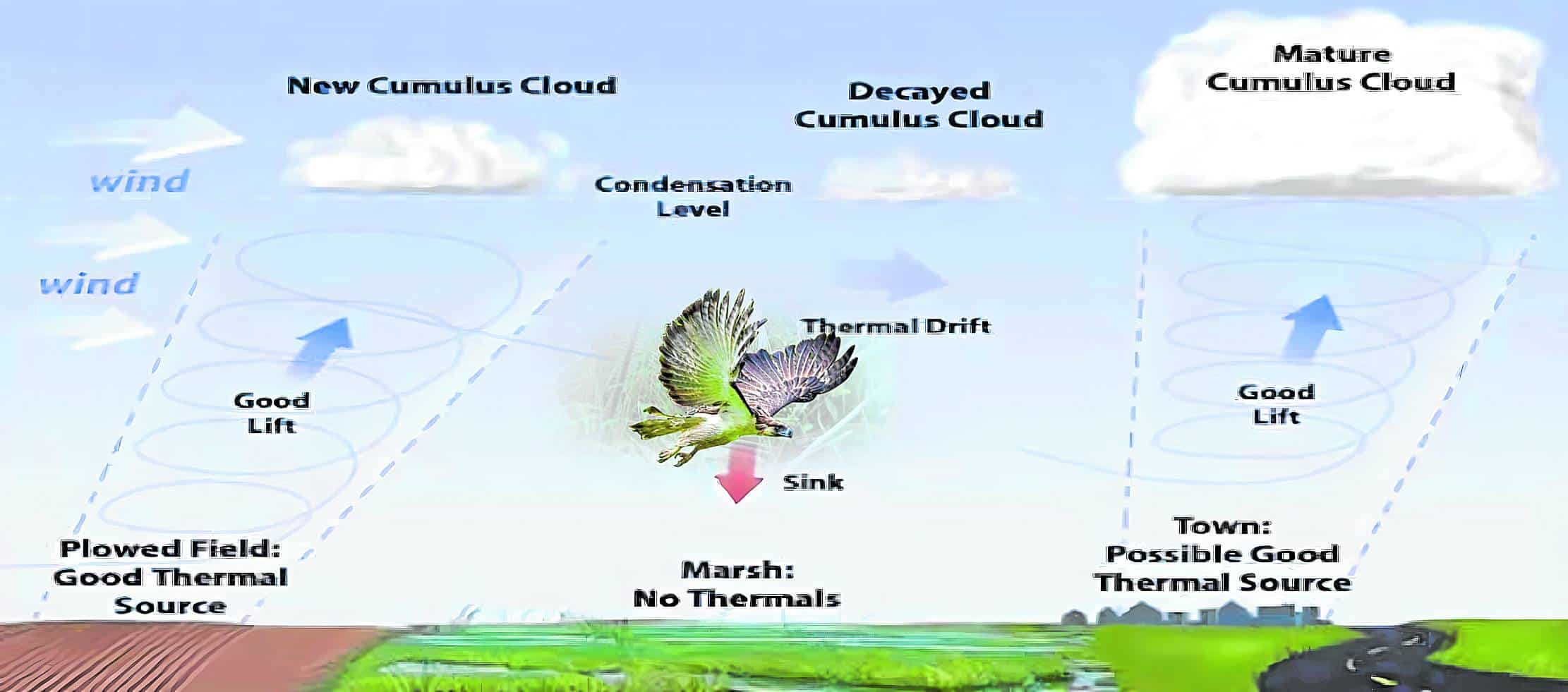

Lastly, they are not fit for overwater flights. “The wings and body plan of an eagle are not fit for overwater flights. They have large and broad wings but these are built for catching and riding columns of hot air rising above the land, called thermal updrafts,” Ibañez said.

“Eagles glide from one thermal to the next. They rarely flap their wings. This is their survival strategy to save them energy. But out in the sea where thermals are unstable at best, they risk crashing and drowning,” he added.

Thermal updrafts are columns of hot air rising over lands and mountainsides, allowing eagles to fly over the landscape and at great distances.

SEA CRASH An illustration prepared by Phiippine Eagle Foundation experts shows the circumstances leading to Uswag’s crash off the coast of Baybay City.

Immature birds

What has brought Uswag to the coasts?

“Released immature eagles, because they are not as experienced and have no territories yet, face the same challenges that all dispersing immature eagles face in the wild: shooting, trapping, diseases, climate extremes, starvation and sea crashes that might result in drowning,” said Ibañez.

“Immature birds, being still naive and less skilled and inexperienced mean they are vulnerable,” including being unable to determine when a stretch of thermal updraft is about to end and is taking it over a water body, he added.

Wind, temperature and land breeze, according to Ibañez, might also influence the movement of the eagles away from land.

“But as they mature, and learn the ways of the wild, their survival chances increase. Along the way, the weaker ones perish, which by virtue of evolution via natural selection and differential survival, is good for the population overall, because the death of the weaker ones means the fit and robust eagles remain to perpetuate the species,” he further said.

Further study

The case of Uswag is the ninth recorded, so far, of eagles straying from the forests into a body of water. All eight happened in Mindanao, with the eighth case resulting in the death by drowning of a raptor in Sarangani province.

But Ibañez said there could be more cases that had not been recorded.

At this stage of conservation efforts, with only about 392 pairs of the critically endangered national birds remaining in the wild, conservationists are turning greater interests on this phenomenon, if only to help mitigate possible sea crashes

“It is pushing us to invest into studying this further and examine its role in extirpating populations on small islands and in coastal forests,” said Salvador.

PH EAGLE CONSERVATION: HOPE IN LEYTE, DESPAIR IN CEBU

June 11 – Philippine eagles “Uswag” and “Carlito” arrive in Tacloban City, Leyte, on board a Philippine Air Force C295 plane from Davao City.

June 11 to June 27 – Pair undergoes acclimatization.

June 28 – Uswag and Carlito are released at Marabong watershed within the Anonang-Lobi mountain range near Barangay Kagbana in Burauen, Leyte.

July 9 – GPS readings show Uswag at Anonang-Lobi mountain range.

July 30 – GPS fixes from Uswag’s transmitter suggest he is already at sea off Baybay City.

Aug. 1 – Search starts on the shoreline of Baybay City.

Aug. 2 – Search expands to Cuatros Islas.

Aug. 3 – Search team heads to northern Pilar’s Ponson Island in Cebu at 9:30 a.m. Team members board a motorized fishing boat an hour later. New batch of GPS fixes received at 11:24 a.m. show Uswag about half a kilometer away from the shores of Barangay Cawit, Pilar town. At 3:30 p.m., Uswag’s decomposing carcass is found floating with sea debris.