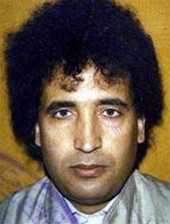

File photo of Libyan Abdel Baset al-Megrahi who was found guilty of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing of a PanAm flight over Scotland that killed 270 people. (AP Photo)

BENGHAZI, Libya — Abdel Baset al-Megrahi, a Libyan intelligence officer who was the only person ever convicted in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, died Sunday nearly three years after he was released from a Scottish prison to the outrage of the relatives of the attack’s 270 victims. He was 60.

Scotland released al-Megrahi on Aug. 20, 2009, on compassionate grounds to let him return home to die after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. At the time, doctors predicted he had only three months to live.

Anger over the release was further stoked by the hero’s welcome he received on his arrival in Libya – and by subsequent allegations that London had sought his release to preserve business interests in the oil-rich North African nation, strongly denied by the British and Scottish governments.

After his release, he kept a strict silence, living in the family villa surrounded by high walls in a posh Tripoli neighborhood, mostly bedridden or taking a few steps with a cane. Libyan authorities sealed him off from public access. When the one-year anniversary of his release passed, some who visited him said al-Megrahi bitterly mused that the world was rooting for him to die.

His son, Khaled al-Megrahi, confirmed that he died in Tripoli in a telephone interview but hung up before giving more details.

To the end, al-Megrahi insisted he had nothing to do with the bombing, which killed 270 people, most of them Americans.

“I am an innocent man,” al-Megrahi said in his last interview, published in several British papers in December. “I am about to die and I ask now to be left in peace with my family.”

The fall of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi in August – and his death two months later – has so far done nothing to dispel the mysteries that surround the case even after al-Megrahi’s conviction. The U.S., Britain, and prosecutors in his trial contended that he did not act alone and carried out the bombing at the behest of Libyan intelligence. After Gadhafi’s fall, Britain asked Libya’s new rulers to help fully investigate but they put off any probe for the forseeable future.

They also rejected Western pressure to jail or return al-Megrahi.

“He is between life and death, so what difference would prison make?” his brother, Abdel-Nasser al-Megrahi, said at the time.

Little was known about al-Megrahi. At his trial, he was described as the “airport security” chief for Libyan intelligence, and witnesses reported him negotiating deals to buy equipment for Libya’s secret service and military.

But he became a central figure in both Libya’s falling out with the West and then its re-emergence from the cold.

To Libyans, he was a folk hero, an innocent scapegoat used by the West to turn their country into a pariah. The regime presented his handover to Scotland in 1999 as a necessary sacrifice to restore Libya’s relations with the world.

In the months ahead of his release, Tripoli put enormous pressure on Britain, warning that if the ailing al-Megrahi died in a Scottish prison, all British commercial activity in Libya would be cut off and a wave of demonstrations would erupt outside British embassies, according to leaked U.S. diplomatic memos. The Libyans even implied “that the welfare of U.K. diplomats and citizens in Libya would be at risk,” the memos say.

But in the eyes of many Americans and Europeans, he was the foot-soldier carrying out orders from Gadhafi’s regime. Tony Blair, Britain’s prime minister at the time of the conviction, said the verdict “confirms our long-standing suspicion that Libya instigated the Lockerbie bombing.”

The bombing that blew up Pan Am Flight 103 on Dec. 21, 1988, over Lockerbie, Scotland was one of the deadliest terror attacks in modern history. The flight was heading to New York from London’s Heathrow airport and many of the victims were American college students flying home to for Christmas.

Gadhafi handed over al-Megrahi and a second suspect to Scottish authorities after years of punishing U.N. sanctions. Four years later, in 2003, Gadhafi acknowledged responsibility – though not guilt – for the Lockerbie bombing and paid compensation of about $2.7 billion to the Lockerbie victims’ families. He also pledged to dismantle all weapons of mass destruction and joined the U.S.-led war on terror.

The regime maintained it handed al-Megrahi over and paid compensation only to win the lifting of sanctions. The steps won Gadhafi quick rewards, with Western powers resuming diplomatic contacts and signing lucrative business deals.

In 2001, a Scottish court – set up in the neutral ground of a military base in the Netherlands – convicted al-Megrahi of planting the bomb but acquitted his co-defendant, Lamen Khalifa Fhimah, a Libyan Arab Airlines official, of all charges. El-Megrahi ended up serving eight years of a life sentence.

The prosecution’s case was built around a tiny fragment of circuit board discovered among the airline wreckage that investigators determined was part of the timer of the bomb, hidden in a suitcase. Investigators said the suitcase was loaded onto a flight from Malta, booked through to Pan Am 103 via Frankfurt.

An executive from a Swiss company testified that he had sold timers of the same make to Libya. Investigators found that al-Megrahi traveled to Malta on a false passport a day before the suitcase was checked in and left the following day.

Key to convicting al-Megrahi was the testimony of a Malta shopkeeper who identified him as having bought a man’s shirt in his store. Scraps of the garment were found wrapped around the timing device.

However, a Scottish judicial body that carried out a major review of the evidence cast doubt on the shopowner’s ID of al-Megrahi and said there was evidence the shirt was purchased on a day when al-Megrahi was not in Malta.

Al-Megrahi’s lawyers also claimed that British and U.S. authorities tampered with evidence, disregarded witness statements and steered investigators away from suggestions the bombing was an Iranian-financed plot carried out by Palestinians to avenge the shooting down of a civilian Iranian airliner by a US warship – in which some 290 people were killed – several months before the Lockerbie bombing. The judicial body, however, discounted theories of intentional misdirection.

Al-Megrahi had appealed his conviction, but had to drop the appeal to be eligible for compassionate release.

“I say in the clearest possible terms, which I hope every person in every land will hear – all of this I have had to endure for something that I did not do,” al-Megrahi said in a statement after his release.

“I had most to gain and nothing to lose about the whole truth coming out – until my diagnosis of cancer,” he said. “To those victims’ relatives who can bear to hear me say this, they continue to have my sincere sympathy for the unimaginable loss that they have suffered.”

Some of the victims’ families in Britain are also not convinced of al-Megrahi’s guilt.

“By abandoning his appeal, we the families will be robbed of the opportunity to find justice,” the Rev. John Mosey, whose daughter Helga died aboard Flight 103, said in 2009.

“I came away from the court 85 percent convinced he did not do it, based on the evidence I heard,” said Mosey, who is from Cumbria, England, and attended all but one week of al-Megrahi’s nine-month trial.

In announcing al-Megrahi’s release from prison, Scottish Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill said he was motivated by Scottish values to show mercy even though al-Megrahi had not shown compassion to his victims.

“Some hurts can never heal, some scars can never fade,” MacAskill said. “Mr. al-Megrahi now faces a sentence imposed by a higher power.”

Al-Megrahi is survived by his wife, Aisha, and five children.