Figures of (that) speech: Some SONA trivia

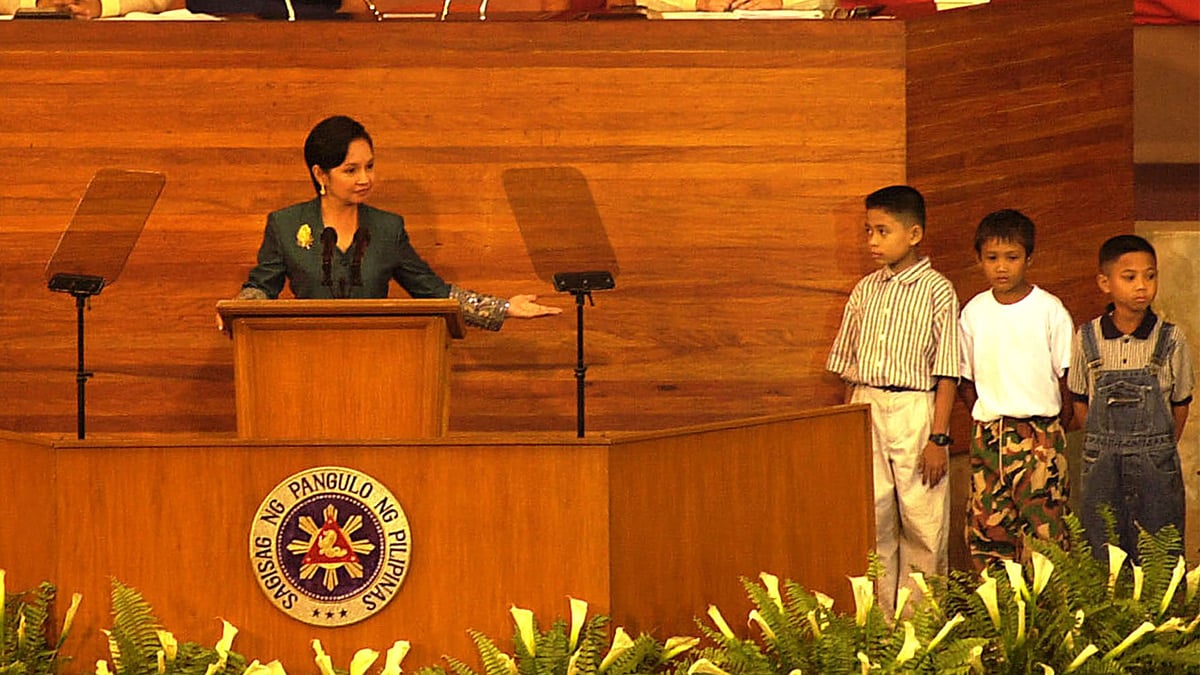

IN THE SAME BOAT Then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo highlighted her 2001 Sona with the “Bangkang Papel Boys.” —Inquirer file photos

MANILA, Philippines — The State of the Nation Address (Sona), the annual presidential speech delivered before a joint session of Congress, one accorded much historic weight and post-event parsing, had what may be considered its earliest versions even before the birth of the republic itself, or when the “N” in Sona was still being conceived.

The paramount leaders of the Philippine revolution against Spain—Andres Bonifacio and Emilio Aguinaldo—made speeches of about the same aspirational mold, offering a vision of the nascent nation’s course.

READ: Marcos ‘fine tuning’ Sona 2024 speech

On March 22, 1897, Bonifacio, as the Supremo of the Katipunan secret society, delivered his “State of the Katipunan Address.” A year later, on Sept. 15, 1898, Aguinaldo, as the country’s first President, gave a congratulatory message before the Malolos Congress that was convened three months after he declared Philippine independence.

But the first Sona under a Philippine Constitution was delivered by then President Manuel L. Quezon on Nov. 25, 1935, at the Legislative Building in Manila (now the National Museum of Fine Arts). The speech became a yearly tradition from then on, with gaps occurring only during World War II and in 1986.

Today, under the 1987 Constitution, the Sona is scheduled every fourth Monday of July.

Certain features—how the speech is structured according to theme, thrust or tone—have become a constant: it primarily serves as the President’s report on the government’s key achievements in the past year or since his or her assumption of office; a fresh round of goal-setting in terms of priority legislation or programs; an acknowledgment of old and new challenges (or threats); and ultimately an assurance that everything remains on course.

Longest, shortest

Filipinos have long been used to Sonas lasting more than an hour. In the post-Edsa period, the record for the longest speech currently belongs to Rodrigo Duterte whose last Sona, in 2021, started at 4:13 p.m. and ended at 6:58 p.m.

That year, the President known for meandering late-night press briefings and foul-mouthed digressions on national TV took two hours and 45 minutes to finish his piece. (In the evening news and the next day’s newspapers, however, Duterte’s swan song was eclipsed in the headlines by Filipino weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz winning the country’s first-ever Olympic gold medal. Such a downgrade was a rarity, if not a first, in Sona history.)

In terms of word count, the longest was in the pre-Edsa era and delivered by Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in 1969, consisting of 29,335 words.

The shortest was by Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, whose 1,556-word Sona in 2005 was over in 25 minutes and 55 seconds. (This was about a month after she said “I am sorry” to the Filipino people over the “Hello Garci” scandal.)

In 2001, Arroyo made her first Sona stand out by having three urban poor boys stand next to her on the dais as she spoke. They were the “Bangkang Papel” youths from the Payatas dump in Quezon City, so called because they caught the government’s attention after they wrote wishes on paper boats and “sent” them to Malacañang via the Pasig River.

NATIVE SPEAKER Then President Benigno Aquino III delivered his Sona in Filipino, breaking a tradition.

Fidel V. Ramos’ first Sona, delivered in 1992, went as far as making a fast-forward to the last year of his term. He already mentioned the preparations needed for the celebration of the Philippine Centennial in 1998.

Before being held traditionally at the Batasang Pambansa Complex in Quezon City, the Sona had different venues in the decades prior. Sergio Osmeña and Manuel Roxas addressed the nation from what was then the temporary home of Congress on Lepanto (now SH Loyola) Street in Manila. Like Quezon before them, Ramon Magsaysay, Carlos P. Garcia and Diosdado Macapagal gave their speeches at the old Legislative Building.

Marcos Sr. used five locations: Malacañang Palace, the Legislative Building, Quirino Grandstand, the Philippine International Convention Center, and Batasan.

On Jan. 23, 1950, Elpidio Quirino delivered his second Sona from his hospital room at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. His Filipino audience back home heard him live on radio.

Since the Cory Aquino presidency, all Sonas have been delivered at Batasan.

All-Pinoy by P-Noy

The speeches have mostly been in English, with just a sprinkling of Filipino.

Joseph Estrada’s 1998 Sona, his first, was made to mirror the “masa” or commonfolk image he sought to project by being mostly in Filipino.

In 2010, Benigno Aquino III, Cory’s only son, became the first to do a Sona entirely in the national language—a style he would keep till his last address.

Naturally, having ruled for 20 years, Marcos Sr. also had the most Sonas.

Osmeña had the least—just one—on June 9, 1945, when the country had just been liberated from Japanese occupation.

Skips and ‘hybrids’

There were no Sonas from 1942 to 1944. The wartime president, Jose P. Laurel, spoke before a special session of the National Assembly on Oct. 18, 1943, but the address was not considered a Sona since the 1943 Constitution did not provide for a presidential report to the legislature.

Swept into power by the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution that ended the Marcos dictatorship, Cory Aquino did not deliver a Sona that year but marked her first 100 days in office on June 4, 1986, with a speech from Malacañang and a panel discussion with her Cabinet members. The country’s first female President delivered her first official Sona in 1987.

Because of restrictions on mass gatherings during the Covid-19 pandemic, Duterte’s Sona in 2020 and 2021 were described as “hybrid” affairs in terms of audience attendance. For his last Sona, only 350 people were allowed inside the Batasan plenary hall to witness it in person. Other VIPs, like then Vice President Leni Robredo, attended virtually. —compiled by Inquirer Research/Sources: Inquirer archives, pco.gov.ph, facebook.com/pcogovph, facebook.com/pia.gov.ph, officialgazette.gov.ph, facebook.com/govph