MANILA, Philippines—As the Philippine government taps waste-to-energy (WTE) technology as a renewable energy resource and a solution to the country’s solid waste management problem, scientists warn about its dreadful impact on human health and the environment.

For years, WTE—which refers to turning waste into energy, either in the form of electricity or heat—has been a controversial issue in the country.

Despite this, in past years, proposals to utilize WTE technology in the Philippines grew louder amid higher demand for more electricity and declining capacity to handle solid waste in the absence of more landfill space.

According to a United Nations (UN) report, the Philippines is the only Asia Pacific country with an incineration ban mandated by law.

The Philippine Clean Air Act of 1999 and the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 prohibit incineration, defined as the burning of municipal, biomedical, and hazardous waste, which emits poisonous and toxic fumes.

But the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) in 2019 said the incineration ban was lifted for thermal WTE after guidelines governing WTE use had been approved in 2016.

“The thermal WTE debate continues in the country as the guidelines are contradictory to the Clean Air Act,” UNEP said.

The ban is further under threat after the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) said in 2019 that it is pursuing WTE technologies to help address the growing waste problem in the country.

In November, then-Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu signed the DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 2019-21, which provides guidelines on establishing and operating WTE facilities to treat municipal solid waste (MSW) in the country.

On top of this, over the past few years, several versions of bills have been proposed in Congress seeking to repeal the country’s incineration ban.

The DENR said it is “looking at WTE as a cleaner and more sustainable alternative to the traditional sanitary landfill.” This statement, however, puzzled some experts as several studies have already stressed and proven the potential dangers and environmental harm of WTE.

More harm to the environment

“When you have a technology that has air emissions [that] are very dangerous and affect wildlife, humans, and the environment; when you have wastewater emissions; and you end up with solid waste that’s also hazardous, I cannot imagine why you could call this a ‘clean alternative’,” said Dr. Jorge Emmanuel, adjunct professor of environmental science and of engineering at the Silliman University.

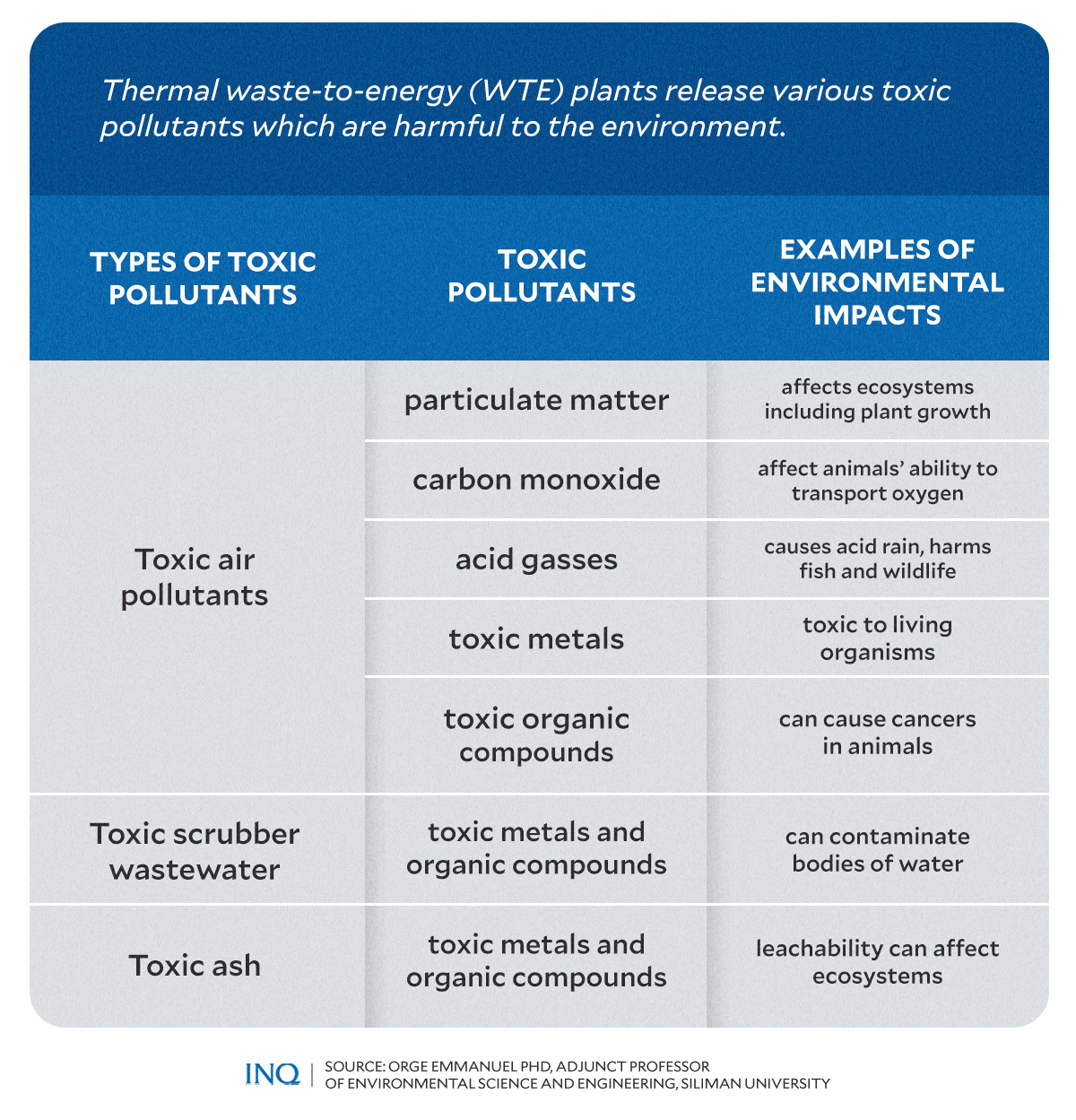

In a roundtable discussion hosted by renowned marine conservation organization Oceana, Emmanuel explained that thermal WTE plants (including traditional incinerators and pyrolysis) and gasification-based incinerators release various pollutants that harm the environment.

These toxic pollutants include those that are emitted into the air, such as:

- particulate matter

- carbon monoxide

- acid gasses

- toxic metals

- toxic organic compounds.

Thermal WTE plants also produce toxic wastewater and ash containing toxic metals and organic compounds.

The byproducts of thermal WTE processes have various impacts on the environment:

- They affect the ecosystem, including plant growth.

- They affect animals’ ability to transport oxygen.

- They cause acid rain, which harms fish and wildlife.

- They are toxic to living organisms.

- They cause cancers in animals.

- They contaminate bodies of water.

Moreover, experts like Emmanuel clarified that establishing and operating more thermal WTE plants might worsen the already significant lack of sanitary landfills in the country.

Last year, the Commission on Audit (COA) found a significant lack of material recovery facilities (MRFs) and sanitary landfills (SLFs), with only 39.05 percent or 16,418 out of 42,046 barangays served by 11,637 total MRFs in 2021.

While some proponents claim that WTE could be a viable alternative to landfills, Emmanuel stressed that toxic ashes produced in thermal WTE facilities require proper disposal, which involves having a specialized landfill.

“The Stockholm Convention guidelines state that the [bottom and flying] ash is hazardous; they need to be disposed of in specialized hazard waste landfills, of which we have very few,” Emmanuel said.

“Most provinces do not have hazardous waste landfills,” he added.

Albrecht Arthur N. Arevalo, climate and anti-incineration campaigner for Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) Asia Pacific, echoed the sentiment.

“You cannot mix toxic ash into regular landfills; it has to be separated into toxic ash landfills,” Arevalo explained during the International Zero Waste Month Symposium held last January 27 in Malaysia.

He emphasized that Singapore—which is heavily reliant on WTE and is considered by lawmakers proposing WTE-related bills as their model country—recognizes the need for more landfills.

On its website, the Singaporean Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment noted that: “incineration plants are very expensive to build and operate. They also take up large areas of land.”

“We cannot keep building more incineration plants indefinitely,” it added, explaining that the reduction of waste and increase in recycling will help delay the building of new incineration plants in the country.

Serious health impacts

Last year, Senator Raffy Tulfo, who also chairs the Senate committee on energy, met with Singaporean Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu and did a site inspection of the Keppel Seghers Tuas WTE Plant (KSTP).

He described the construction of WTE plants in Singapore as “safe” and “without risk.”

However, experts and the international zero waste advocacy group GAIA stressed that WTE incinerators are not only financially costly and harmful to the environment, but they also pose considerable risks to the health of neighboring communities and the general population.

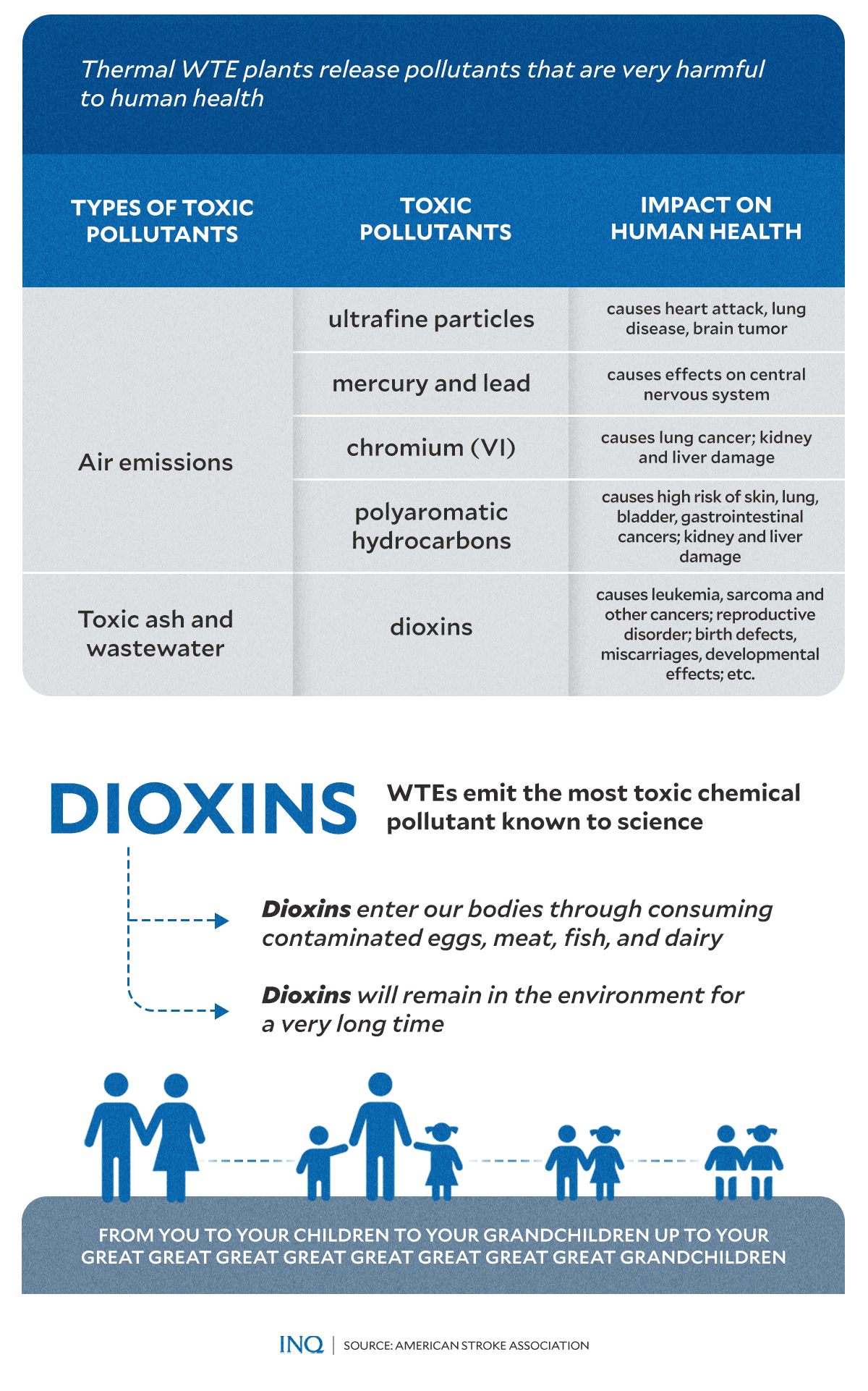

“In a typical waste-to-energy plant, the air emissions include ultra-fine particles, and these ultra-fine particles are not even required by our laws to be tested, but they can cause heart attacks, lung disease, etc,” Emmanuel said.

“They also release hazardous metals, for example, mercury and lead, which can affect the central nervous system,” he said.

Aside from these, WTE incinerators emit dioxins, which Emmanuel dubbed as the “most toxic chemical pollutant known to science.”

“Dioxins, which refer to a family of 210 specific chemicals, have been found to bio-concentrate up the food chain,” he said.

“[This] means, for example, if the dioxin in a river or lake has units of one party per trillion (ppt). [I]f you measure the dioxins in the fish [from the same river or lake], they are typically much higher […] it could be as high as 29,000 ppt,” Emmanuel explained.

“That’s what we mean by bio-concentration; organisms like fish can bio-concentrate it, so [humans] get a higher dose when we eat them as we go up the food chain,” he continued.

Dioxins can be inhaled by people living near WTE plants. However, most dioxins enter the human body after consumption of eggs, meat, fish, and other dairy products containing a bio-concentrated amount.

“The dioxins fall into the ground, and the chickens and cows eat it from the grass or the soil and bio-concentrate it,” Emmanuel said.

“If it falls into the water, the fish bio-concentrate it. So we end up eating higher levels of dioxins, and that’s how humans living around waste-to-energy plants end up getting most of their dioxins,” he said.

Among the health effects associated with dioxins are:

- cancers (such as soft-tissue sarcoma, respiratory cancer, prostate cancer, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia)

- male reproductive effects (low sperm count, abnormal testis, reduced size of genital organs, lower testosterone levels)

- female reproductive effects (decreased fertility, ovarian dysfunction, endometriosis, hormonal changes)

- birth defects

- miscarriages

- developmental effects on children (including alteration in reproductive systems and impact on child’s learning ability and attention)

In 2020, the environmental group Greenpeace found that an estimated 27,000 Filipinos already died from air pollution caused by burning fossil fuels, such as in coal plants, as well as from transport pollution.

“Allowing waste-to-energy (WTE) incinerators to operate will add to the harm and deaths air pollution brings to people,” the group said.

Dioxins in various WTE

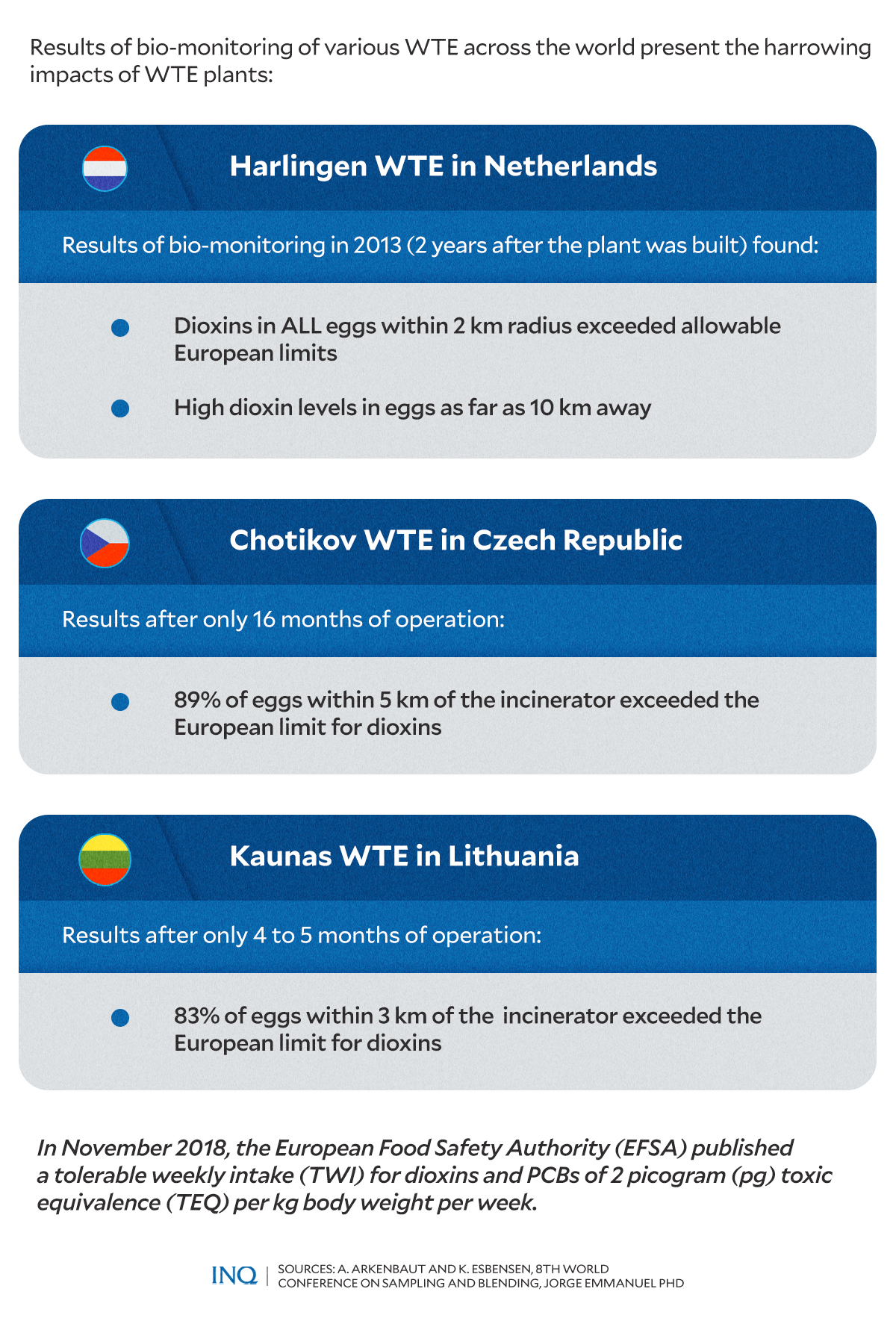

According to GAIA, even incinerators with “state-of-the-art” pollution control devices could still emit vast amounts of dioxins, which make nearby communities highly vulnerable.

An example is the Harlingen WTE facility in the Netherlands, built in 2011 and described by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs as “the best incinerator in Western Europe.”

A study, however, found that continuous monitoring from 2015 to 2017 showed that periodic tests twice a year underestimated dioxin emissions by 460 to 1,290 times.

Results of bio-monitoring in 2013 also showed that dioxins in all eggs within a two-kilometer (km) radius of the plant exceeded the allowable European limits. High dioxin levels were also detected in eggs as far as 10 km away.

In the Czech Republic, a study found that after only 16 months of operation of the Chotikov WTE facility, 89 percent of eggs within five km of the incinerator exceeded the European limit for dioxins. Similarly, the Kaunas WTE in Lithuania, after only four to five months of operation since November 2020, showed that 83 percent of eggs within 3 km of the incinerators exceeded the European limit for dioxins.

According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the tolerable weekly intake (TWI) for dioxins is 2 picogram (pg) toxic equivalence (TEQ) per kg body weight per week. Imagine a single grain of sand, a picogram is much smaller than this.

A recent incident also occurred in France last year wherein French health authorities issued warnings to its residents not to eat eggs from domestic coops in the Île de France region.

The warning came after studies confirmed that soil and eggs in domestic chicken coops near the largest waste incinerator in Europe (located in Paris) are contaminated by Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) such as dioxins and furans.

Dioxin regulation in PH?

Emmanuel, who was among the experts who put together the Stockholm Convention guidelines, said the Philippines follows the guidelines for dioxins in air, which says dioxin levels cannot exceed .1 nanograms TEQ per normal cubic meter (Nm3) emitted into the air.

The guidelines also imposed a limit for wastewater—1 nanogram TEQ per liter of wastewater—which, Emmanuel stressed, is currently not in any of the Philippine laws.

He also noted that he, along with many other scientists, discovered that the periodic testing that’s in the Stockholm guidelines, requiring tests for dioxin once or twice a year, is no longer reliable as studies in the last 10 years or so have shown that dioxins can go “very very high” at different times of the day.

“The periodic testing that’s in the Stockholm guidelines is no longer considered, in my view and many scientists, as really being protective of public health and the environment,” said Emmanuel.

“This is the problem we have; we need to go through continuous dioxin monitoring, which the Philippines today is not capable of doing,” he continued.

Another problem with dioxins, Emmanuel stressed, is that they stay in the environment for hundreds of years.

He explained that if dioxins produced in WTE plants today fall on the ground and are covered by at least 2 centimeters of soil, it will take 10 to 40 generations for most of the dioxins to disappear.

“I’m reminded of Laudato si’ of Pope Francis, where he reminds us that when we think of the environment, we have to think of what happens to future generations. […] [D]ioxins can impact many generations, hence, not just us, not just our children, but many, many generations after,” he said.

RELATED STORIES:

Risks loom as worsening garbage mess pushes deep PH dive into waste-to-energy