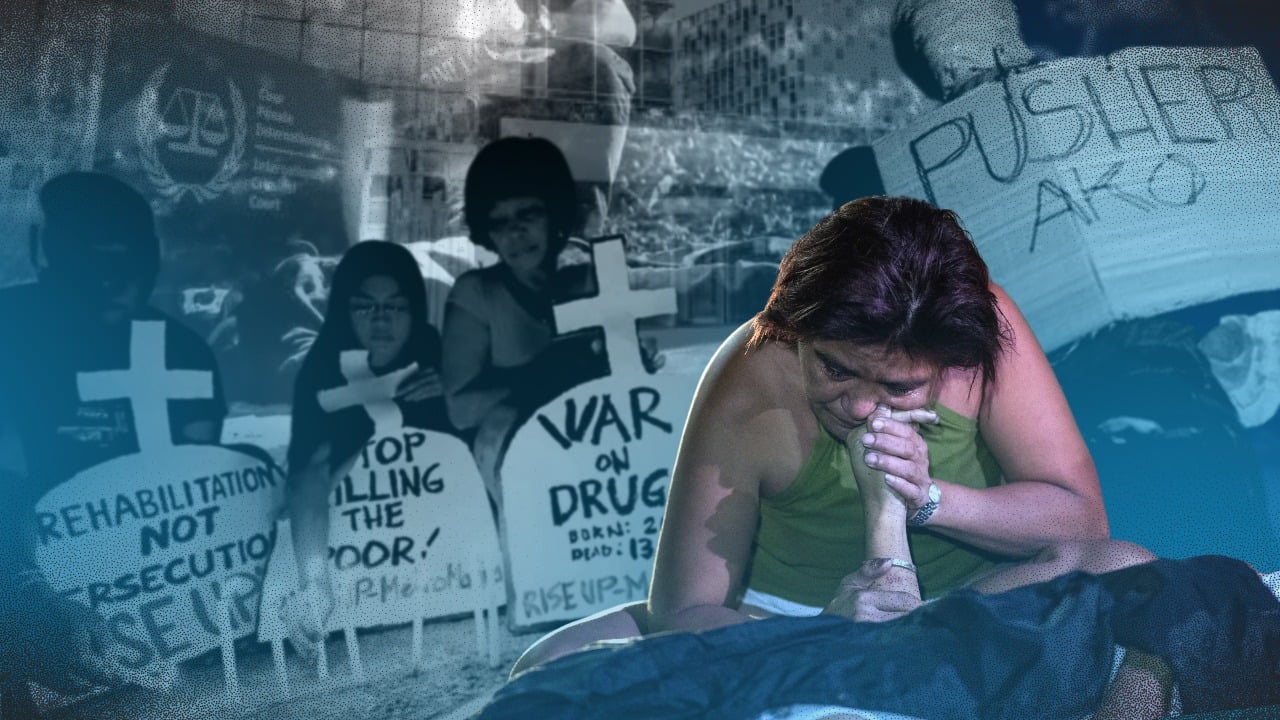

Composite image/Inquirer file photo

MANILA, Philippines — More than six years have passed but Arlene Gibaga still remembers how plainclothes police carrying out the government’s brutal war on drugs killed her partner, Sherwin Bitas, near their house in Tondo, Manila.

The police arrived at their community in Barangay 19 on Oct. 11, 2017, and ordered Gibaga to show Bitas’ identification card.

She warned them not to do anything to her partner as there were security cameras around the neighborhood.

But that did not stop them.

READ: House panel ready to probe into anti-drug war, extra-judicial killings

Gibaga said they pointed their guns at her and ordered her to hide. She did and she believed that was the moment when they tinkered with the cameras before they shot Bitas and two other men.

The police identified all three as drug suspects killed in a buy-bust operation, according to the Manila Police District.

The police offered her some assistance but she could not make herself receive help from the same people who killed her partner, a “strong-willed” and “loving father” to their three children.

After receiving threats to the lives of her children, Gibaga was forced to sign a prepared statement a month later saying that she was not present when the police killed Bitas.

Still, she sought justice for him, submitting a human rights violation complaint to the Commission on Human Rights (CHR)

It took four years for the CHR to tell her that it found “insufficient evidence” to prove that human rights were violated when Bitas was killed.

After pressing for a reconsideration, the commission reversed its findings and recommended criminal and administrative charges against the officers involved. The CHR also offered her a financial assistance of P20,000.

Gibaga’s story is just one of the 10 accounts documented by the Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services (IDEALS) Inc. in its recently published study, “Pathways to Justice: A Public Report on Domestic Accountability.”

The report noted that she was desperate for justice and retribution against the officers who gunned down the father of her children as she asked during the interview: “Can I shoot them, too?”

“I want them to experience what Sherwin experienced. I want their wives to go through what I did,” she said.

Despite the current administration’s claim that the Philippines’ criminal justice system is “fully functioning,” the nonprofit group of human rights lawyers found that family members of drug war victims see a government “lacking in sincere effort” and a “slow court system” that hindered their search for accountability.

Based on its investigation, IDEALS found that 95 percent, or 92 out of 97 of the alleged extrajudicial killings (EJKs) it examined were either never investigated or were not followed up after the routine initial inquiries by the authorities.

In preparing its 84-page report, the group spoke with members of 10 families who lost relatives in the antidrug campaign of the Duterte administration and tried to seek accountability through various channels.

‘Brief questioning’

The in-depth interviews with Gibaga and the others were conducted from August to September 2023 in Metro Manila.

“The general consensus from victims and their families is that there are no genuine investigations, completed or ongoing, from the Philippine government and its agents,” according to the IDEALS survey organized in partnership with the AJ Kalinga Foundation.

A total of 48 out of 97 respondents said that there was “some form of an investigation around the time of killing.” But after “brief questioning” by the police following the killings, IDEALS said that “generally, no other investigations were made for the purpose of uncovering the truth” about what happened.

Only five of the 48 respondents stated that there was a follow-up investigation of the cases.

“This puts into question the genuineness of the government’s intentions to investigate and prosecute incidents related to the campaign against illegal drugs,” IDEALS said.

“There were barely any suspects, leads, witnesses or actual evidence gathering in these on-the-spot investigations which could lead to criminal prosecution of the perpetrators,” it added.

During the first inquiry of the House committee on human rights into the drug war last month, Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said the Department of Justice investigated more than 900 complaints against police officers out of the 6,000 drug-related deaths officially acknowledged by the government.

Summon Duterte

However, the DOJ opted to prioritize only 52 cases which had the strongest chances of going to trial, said Guevarra, who served as the justice secretary during former President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration.

ACT Teachers Rep. France Castro and Kabataan Rep. Raoul Manuel said that if the House committee was really interested in pursuing justice for the drug war victims, it should question Duterte himself.

Manuel said the “real reference” used by the Philippine National Police and other government agencies in waging the war on drugs was Duterte’s own pronouncements “that drugs must be eradicated in the country within six months” from the time he took office.

Manuel took offense at Duterte’s executive secretary, Salvador Medialdea, for laughing off the prospect of Duterte being called to the hearings which began last month as a belated legislative effort to pursue accountability in the drug war.

“Why is that funny?” he asked. “If they’re so proud of their own numbers that they killed 20,000 civilians in just two years, then why is it suddenly ludicrous for them to explain that?”

“We shouldn’t tolerate that because it seems like this is all just a joke to them,” Manuel added.

During last Wednesday’s hearing, human rights lawyer Jose Manuel Diokno informed lawmakers that the Office of the President had reported that more than 20,000 people were killed in the drug war between July 1, 2016 and Nov. 27, 2017.

That figure, Diokno pointed out, was much higher than the official police record of over 6,000 deaths during the entire Duterte administration.

He added that there was sufficient evidence to charge Duterte for the thousands killed in his drug war, but the authorities were unwilling or unable to pursue these cases. —with a report from Krixia Subingsubing