Redemption of the Macabebes

MACABEBE, PAMPANGA, Philippines — When the ancestors of this coastal town are bluntly tagged “traitors” or subtly branded as “dugong-aso” (loyal to a fault) for choosing to side with colonial rulers, or blamed for the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo and fall of the First Philippine Republic, Vice Mayor Vince Flores takes time to explain the “unjust labeling.”

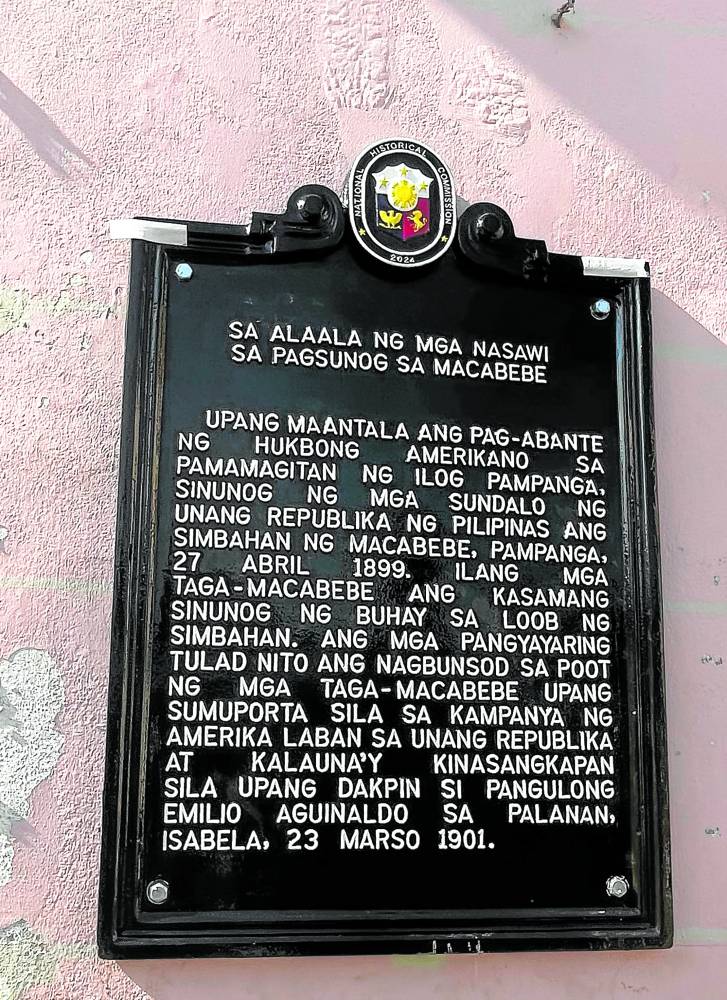

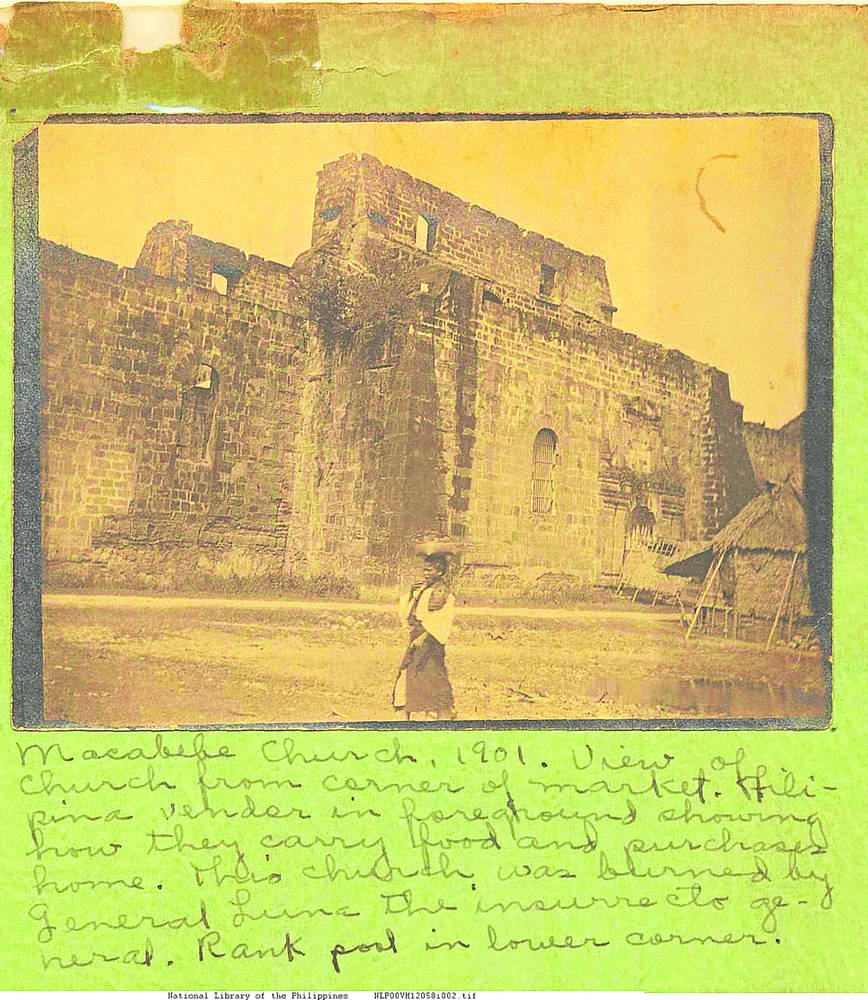

So when the National Historical Commission of the Philippines recently installed a marker confirming that revolutionaries torched the town and massacred around 300 residents by burning them alive inside the San Nicolas de Tolentino church 125 years ago on April 27, 1899, Flores considers that official act from the government as helpful in correcting the historical injustice thrown at these Kapampangans.

READ: A showcase of glorious past in vibrant present

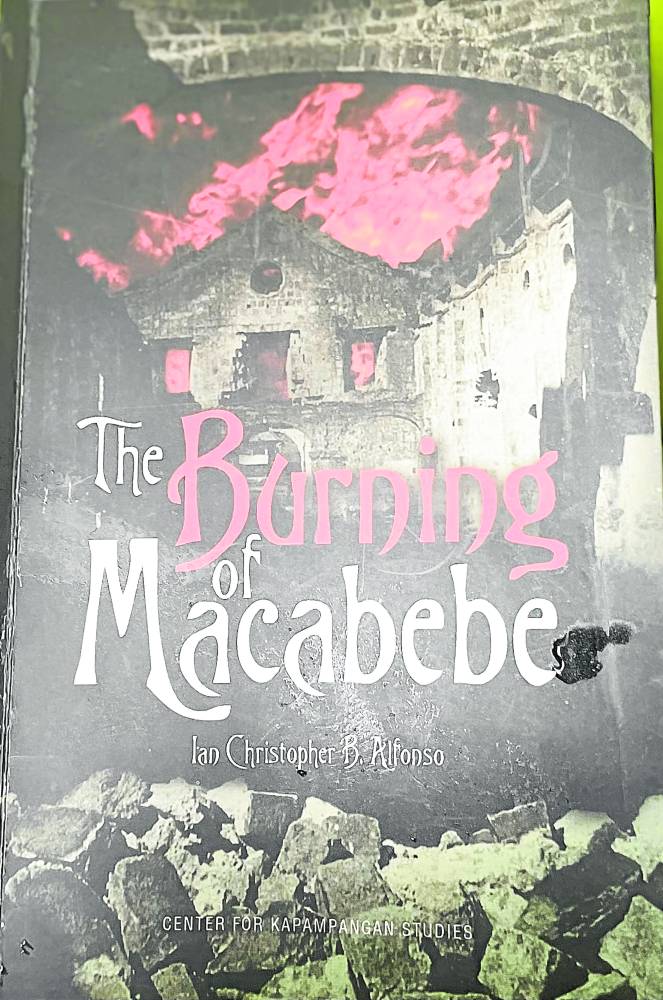

Then there is Ian Christopher Alfonso’s book, “The Burning of Macabebe.” It gives context to the derogatory descriptions, arming the younger ones with knowledge that he hopes will dispel disrespect.

The youth of the town should “be proud as Macabebes,” he says in a phone interview on May 16.

Published by the Center for Kapampangan Studies (CKS) of the Holy Angel University in time for the 125th year of Philippine independence and nationhood, Alfonso’s work is seen as unique and reliable because it revisited primary sources such as the Philippine Revolutionary Records (PRR) of the National Library of the Philippines, Cuerpo de Vigilancia de Manila of the National Archives of the Philippines, published memoirs of the Philippine Revolution both by Filipinos and Spaniards, and newspapers of those times. The 33-year-old historian adds local history in the easy-to-read but in-depth 240-page book launched on May 17.

“It is more of presenting the side of the Macabebe based on primary sources,” he replied when asked if his research was a personal cause since Macabebe is his hometown and his great grandfather, Engracio, served as interim mayor in 1899. With no bit of antagonism against the Tagalogs, Alfonso dedicates the book to the “victims” of the divide and conquer policy during the Philippine Revolution of 1896-1898 and the Philippine-American War of 1899-1913.

The topic, he explains, is “unsettling since this will place our revered founders, heroes and martyrs of Philippine independence and nationhood in a bad light. But as a nationalist historian and, at the same time, a native of Macabebe, it is my responsibility to show both sides of the story why our ancestors—both the freedom fighters and the pro-American Macabebe soldiers—ended up fighting each other.”

From resistance to loyalty

Robby Tantingco, CKS director, noted that Macabebe began with a respectable past. The “brave youth from Macabebe” emerged as the first freedom martyr fighting Spanish colonization in the Battle of Bangkusay in 1571.

The burning of 300 Macabebes came to Tantingco as a “shocking act of cruelty that’s unprecedented in Philippine history.”

According to Tantingco, the event “traumatized the town so much that almost nobody has since talked about it, except in scattered indirect references.”

The book, according to historian Dr. Jose Andres L. Diaz, provides an “insightful look into the reasons behind a long-time prejudice against a group that needs to be understood.”

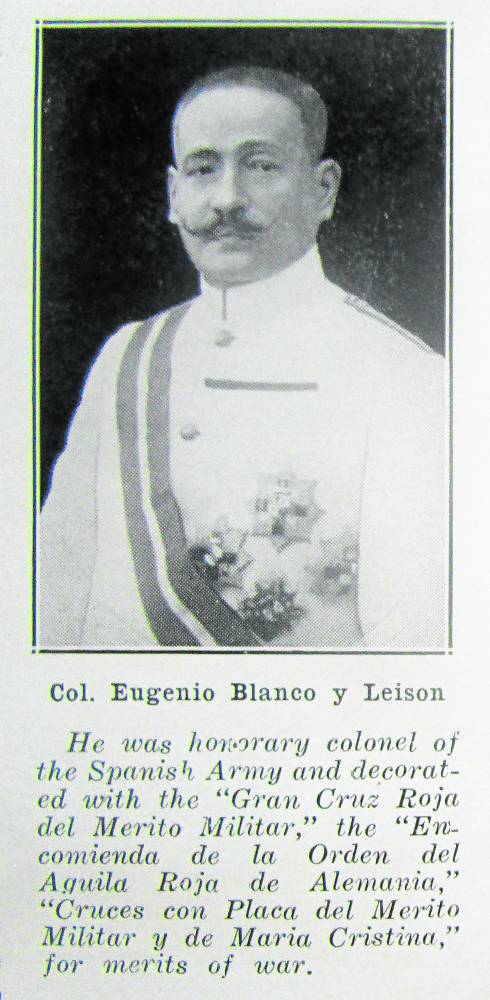

Before presenting details of why the people received the wrath of the revolutionaries —the result of the town being located at the mouth of Manila Bay; the settling of Spanish businessman Don Juan Blanco, who raised his sons Eugenio and Agustin in the town; the killing of Agustin in a battle with Aguinaldo’s forces; Eugenio’s recruitment and arming of the Voluntarios de Macabebe; Eugenio’s securing of the family of Governor General Basilio Agustin; his hosting of the Spanish military command in North Luzon; and the evacuation of Spaniards via the bay—Alfonso began with a framework.

It was from Apolinario Mabini, head of the government committee. Among the stalwarts of the republic, it was Mabini who came to Macabebe’s defense.

“For the sake of those good Makabebes, we should respect the name of the town that gave them birth… [Let] us not rob the good Makabebes of the chance to repair the damage brought about by their evil townmates, and restore them to our common cause to vindicate the honor of their native town,” he wrote in “Seamos Justos” (Let us be fair) in November 1899. Mabini was upset by the “practice to call Makabebes those Filipinos who, lured by the money of the Americans, work with them in the subjugation campaign either as spies or as soldiers or workers.”

Firstly, there was policy. Gen. Antonio Luna ordered the burning of towns and churches from Caloocan to Pampanga to “deprive the Americans of structures that may be used to their advantage.”

Sword and fire

But it was only Macabebe that experienced Luna’s sangre y fuego (sword and fire), in the words of Gen. Jose Alejandrino, a Kapampangan.

Alfonso clarified that Alejandrino did not confirm if Luna went to Macabebe to appease the rumors of annihilating the folks.

But the burning of the town on the same day that American soldiers breached the trenches in Bagbag in nearby Calumpit, Bulacan, “contributed to the hatred of the Macabebe townspeople against Luna, President Emilio Aguinaldo, Republican forces and their supporters.”

Avenging Agustin’s death on Sept. 26, 1896, was found to be Eugenio’s motivation for forming the unit. His appointment as justice of the peace from 1896 to 1898 added to his zeal for keeping peace and order, such that the volunteers of Macabebe and nearby Apalit fought side by side with Spaniards against troops of Gen. Francisco Makabulos on the slopes of Mt. Arayat in 1897.

“Macabebe’s townspeople had no inkling it would be embroiled in the armed conflict because of these siblings,” Alfonso points out.

Eugenio, according to Alfonso, “remained loyal to Spain by leading his voluntarios to fight the rebels in Bataan, Bacolor and Malolos.”

It was Gen. Maximino Hizon, Pampanga commander, who first ordered the destruction of Macabebe should Eugenio not surrender and join the revolution in a week’s time.

Col. Joaquin Cordero issued the warning in a circular, which showed that the “threat to destroy Macabebe was not unique to Luna alone during the Philippine-American War. The town was already threatened during the Revolution of 1898.”

By June, Eugenio and Hizon agreed to negotiate a truce, which fell off because Aguinaldo appointed Gen.Tomas Mascardo in place of Hizon who was court-martialed.

While Alfonso mentioned that the PRR were “silent about the retaliation on the townspeople of Macabebe,” Mabini wrote about the “excesses of the Filipino revolutionaries—later the soldiers of the Republic—especially in Macabebe, where [Eugenio] Blanco did cause much harm to the defenseless and loyal population.”

The burning of 300 Macabebes was confirmed by Gen. Frederick Funston, Aguinaldo’s captor, in a March 8, 1902 speech in New York.

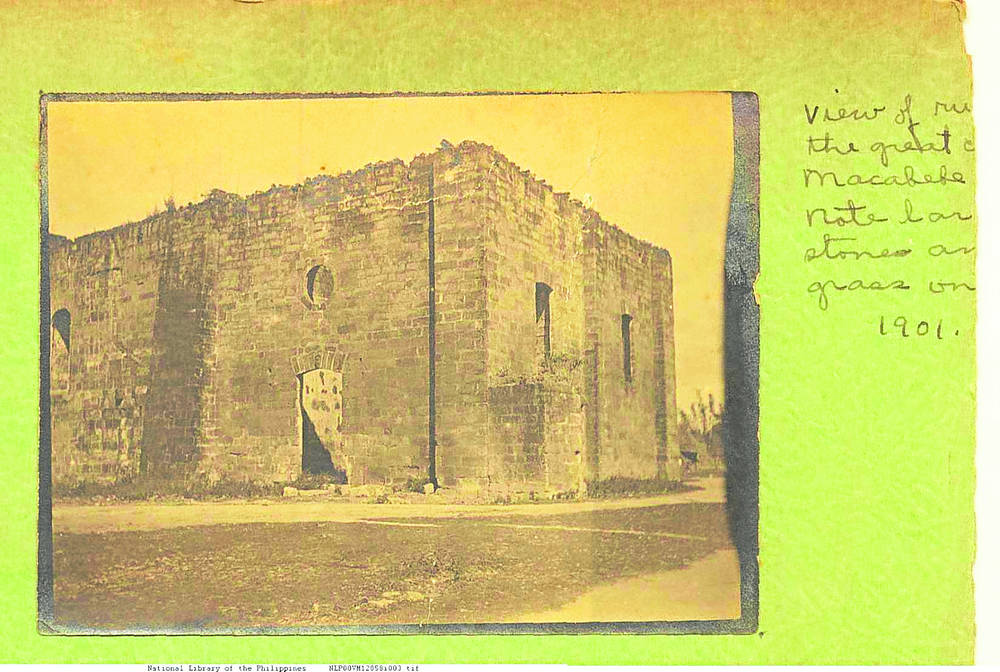

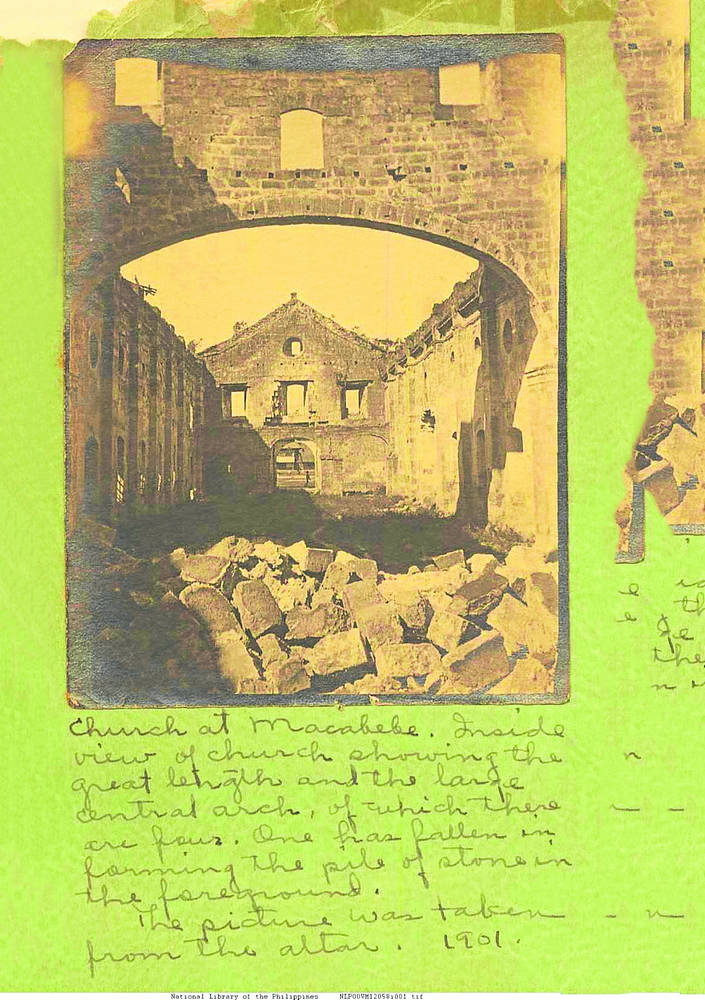

Photographs with handwritten notes in 1901 by American educator Luther Parker also cited the incident.

Alfonso said he first encountered the burning through Alfonso Leyson Jr., a grandson of the Blancos.

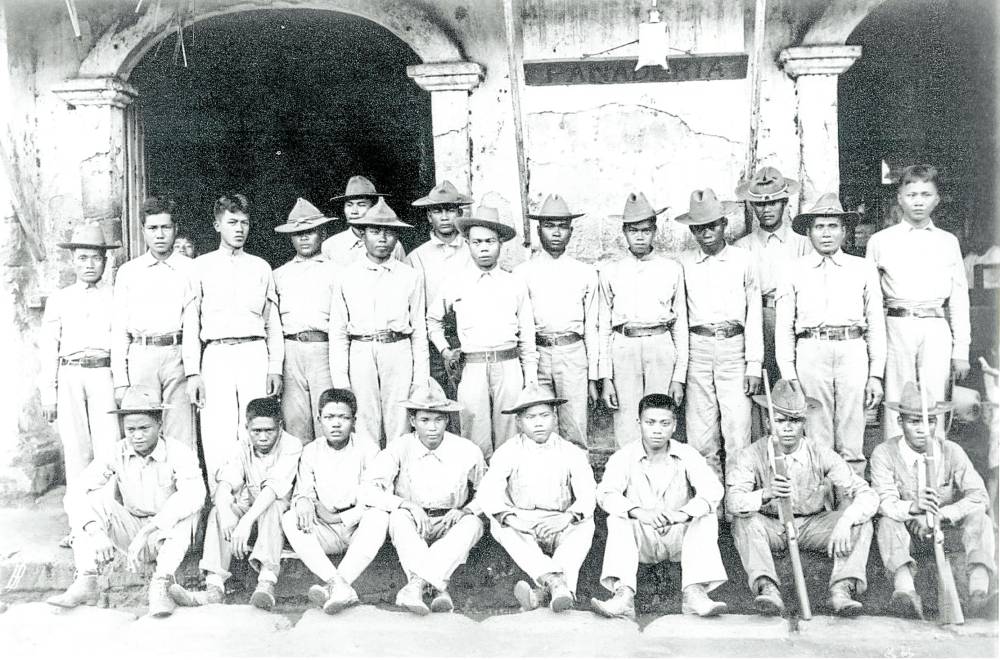

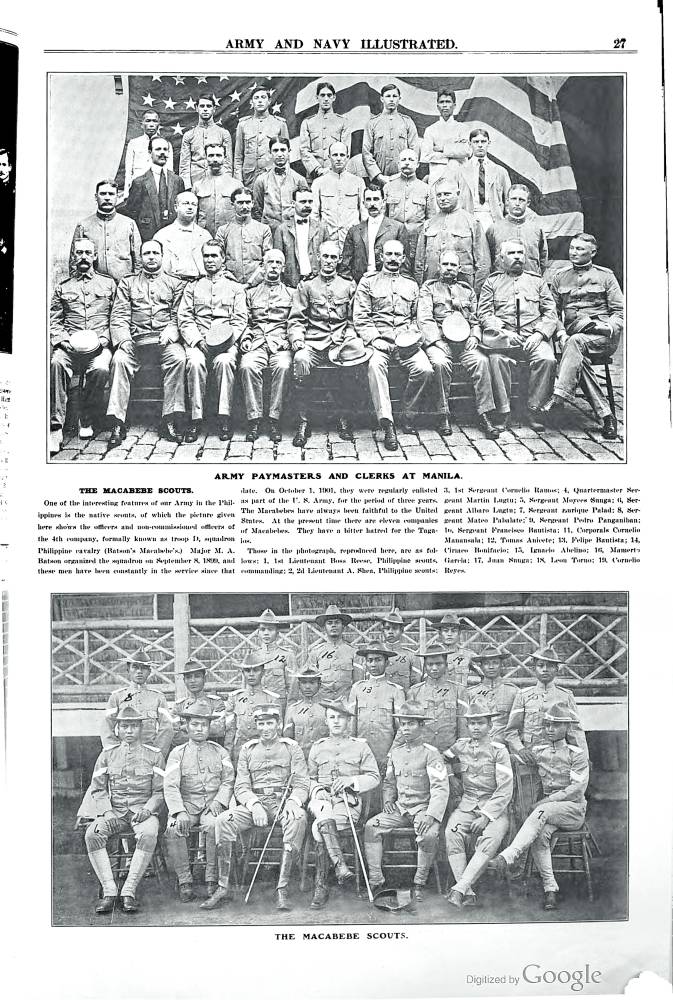

- CORRECTING HISTORY The San Nicolas de Tolentino church Parish (left) in Macabebe, Pampanga, is a silent witness to the cruelty of revolutionaries on townsfolk (see marker below), whose leaders and soldiers (right) were loyal to Spain before shifting allegiance to the Americans. Ian Christopher Alfonso’s book, “The Burning of Macabebe,” revisited primary sources to explain why revolutionaries, later soldiers of the First Republic, were outraged at the Macabebes. —Photos from Cornell University, Center for Kapampangan Studies, and University of Michigan Digital Library and tonette orejas

Leyson recalled in a 2007 comment on a defunct website: “My father told me that when the Katipuneros invaded Macabebe, they took all the men inside the church and lined it with bamboos (sic) to burn them all. The Sungas begged the insurrectos to spare the men and just burn the church.”

‘General Kalintog’

But who was responsible for the burning of Macabebe? It was not Luna, Alfonso learned. The 1953 Historical Data Papers (HDP) for Macabebe mentioned the burning of the Macabebe church but did “not involve Luna, which was strange, for he was too popular a historical figure to be forgotten by the old folks.”

The HDP revealed a name, that of a certain General Kalintog or Kalentong. It was “probably” Col. Agapito Bonzon of Cavite, said Alfonso.

He found General Kalentong to be a mystery. “Could this be Agapito Bonzon known as Coronel Yntong, infamous for arresting Andres Bonifacio in 1897? This was not a remote possibility since the PRR showed he was sent to Macabebe by Aguinaldo to help Gen. Isidoro Torres capture the town in June 1898. In fact, a document signed by Bonzon on June 28, 1898, in Macabebe in the PRR details his presence and involvement in the capture of Macabebe.”