MANILA, Philippines — At the heart of the bustling streets of Manila, passersby may chance upon a self-effacing building on the corner of Doroteo Jose and Alonzo Streets in the Philippines capital. The concrete structure, painted in tangy orange, looks like any other piece of property in the vicinity.

This was the site of the ill-fated six-story Ruby Tower Apartments, which once stood there until a major earthquake caused its collapse in 1968, killing its sleeping residents just before sunrise.

The tragedy prompted the drafting of the National Building Code of the Philippines, which the country has been using for nearly half a century to prevent a repeat of the Ruby Tower Apartment disaster.

Months of analysis by INQUIRER.net found that millions of Metro Manila residents are exposed to earthquake-related hazards because of the weakness of that building code. Records show that lawmakers have tried to amend the code Congress after Congress, to no avail.

With a hodgepodge of buildings that, at best, comply with an inadequate code and at worst, are built to no code at all, Metro Manila has been described as a “ticking bomb.” Experts suggest it is time to amend the law, as it puts the capital region at risk. But a variety of private business interests may have blocked what many consider a basic public safety measure.

The defining moment

Ponson Chang, a Chinese-Filipino in his 40s, narrated to INQUIRER.net how his father and grandfather survived the magnitude 7.3 earthquake on a Friday, Aug. 2, 1968.

Ponson’s father, Tai Pon, 31 at the time, was expecting his first child with his wife. Tai lived with his wife, his parents, and his sister in Room 511 of Ruby Tower. It was a normal night like any other.

Around 4 am, shaking roused Tai and his wife from sleep. Seconds later, the ceiling collapsed on them. Tai tried to cover his wife from the falling debris, but his legs were pinned by a beam. Everything went dark.

“From pitch darkness, he saw blinding light. After several hours, rescuers removed the concrete blocks that fell on them,” Ponson said in a mix of English and Filipino.

“He and his wife were brought to different hospitals. He learned only later on that his wife died from excessive bleeding,” Ponson said.

“The rest of the members in his household, his younger sister and his mom, died on the spot because a beam fell on their heads,” he added.

The epicenter of the quake was Casiguran, Aurora, more than 200 kilometers northeast of Manila. According to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs), a total of 270 people died and 261 were injured.

On the Rossi-Forel Earthquake Intensity Scale used at that time, residents near the epicenter felt intensity 8 or a “very strong shock.” Manila felt a “strong shock” at intensity 7.

Ruby Tower folded like a pancake, killing 268 people and injuring 260 of its residents. Almost all of the fatalities in that quake were from the apartment building.

According to a journal published by Kerby Alvarez of the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman’s history department, Ruby Tower was built in 1965, just three years before the tragedy.

It housed 90 units or 19 apartments on each floor, while the ground level was reserved for offices. At least 80 families were living in the building, totaling at least 800 individuals.

Alvarez described Ruby Tower as a “grand commercial-residential structure” that cost around P1.5 million to build at that time. It is located in a “relatively exclusive enclave” for the Chinese community in Santa Cruz, Manila.

According to a United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) report in 1969, Ruby Tower’s design appeared to have followed standards for non-seismic areas.

The report found that the apartment building, though considered legally built at the time due to the absence of a building code, used low-strength concrete, and lacked design elements to withstand a strong earthquake, among other deficiencies.

The first building code that mandated safety

The Ruby Tower collapse prompted the administration of then President Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the current president’s father, to write a standardized building code, reducing the risks of a future repeat of the disaster.

On Aug. 26, 1972, Republic Act (RA) No. 6541, or the 1972 National Building Code, was enacted into law, the country’s first.

During martial law, the dictator issued presidential decrees to arrogate lawmaking powers solely upon himself. This meant that all existing laws prior to decrees or proclamations were superseded by his regulations that either amended, repealed or supplemented existing ones.

One such decree was PD No. 1096 issued on Feb. 19, 1977, essentially revising the 1972 Building Code. All the changes were made in the 1970s and the code has not been revised since the 1977 update, making it 47-years-old as of this writing.

These lessons from the past, among others, are just some of the many reasons that architects and engineers are calling for a general review of the 1977 code.

Ponson, who happens to be a practicing architect, is among those advocating for the review, a full-circle moment for him and his paternal family.

Luzon sees building boom in high-risk areas

Earthquakes are a common occurrence in the Philippines due to its geographical location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, a tectonic belt characterized by highly active volcanic and seismic activities.

Given its location, the Philippines is among the top countries most prone to earthquakes. Phivolcs has been recording tremors daily, many of which are too weak to be felt. The biggest impact of quakes has been on Luzon.

On July 16, 1990, a magnitude 7.8 quake jolted Central Luzon, with its epicenter in Nueva Ecija, and was felt in provinces and cities as far as Metro Manila and the Bicol region. This was the strongest and deadliest earthquake in the country in the last 30 years.

Over the past three decades, the country has experienced an average of one major earthquake per year that led to deaths, damage to property, and economic losses, according to data from the Office of Civil Defense (OCD).

The 1990 Luzon earthquake, dubbed as a killer quake, hit most parts of the Cordillera and Central Luzon regions. It accounted for seven out of every 10 quake-related deaths in the last three decades. Many were buried alive in collapsed buildings.

As a result of the quake, at least 1.2 million people were forced out of their homes, lost their jobs, displaced from schools or lost access to power and communication lines. Reports narrated thousands sleeping on streets for fear of aftershocks.

The 1990 Luzon earthquake also brought billions of pesos worth of infrastructure damage, estimated to reach P6.8 billion, in the form of structural cracks or collapse of roads, bridges and other buildings.

Tourism destination Baguio was isolated from the rest of the country by the damage and landslides that blocked access to the city.

The killer quake also saw the biggest number of houses destroyed by earthquakes. Two in five houses either collapsed or became uninhabitable.

Many Filipinos still remember the impact the 1990 earthquake had in their lives. Some fear it may happen again with the threat of the “Big One” hanging over their heads.

Metro Manila’s earthquake hazards

According to a recent report by energy consultancy Utility Bidder, the Philippines is among the top 10 countries with the highest risk for earthquakes in terms of number and magnitude.

No place is more vulnerable than the densely populated National Capital Region (NCR), where the ever-present danger of the Valley Fault System has not deterred the constant stream of arrivals in the area and the frantic boom in construction to accommodate them.

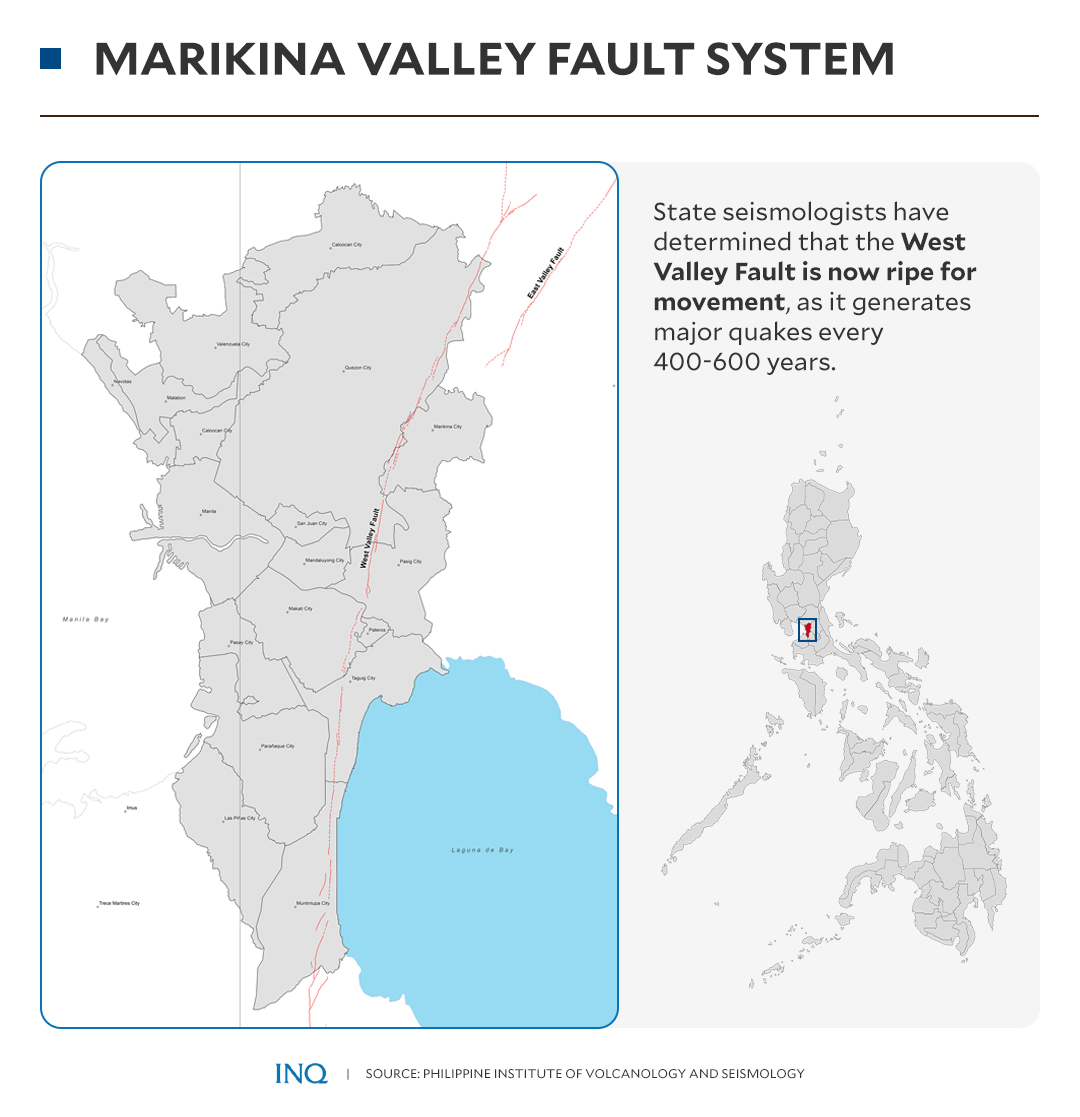

The fault system, also known as the Marikina Valley Fault System, is an active fault zone that includes the 100-kilometer (km) West Valley Fault (WVF) and the 10-km East Valley Fault.

The WVF runs directly under the metropolitan area. It starts in the province of Bulacan, makes its way through Rizal and NCR cities, then down to Southern Luzon in Cavite and Laguna. The East Valley Fault, meanwhile, is in Rizal.

A risk assessment in 2004 by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Philippine government estimated the impact a magnitude 7.2 earthquake would have on the Greater Manila Area, should the WVF move.

According to the 2004 study, this scenario would damage residential structures, where four in 10 houses would collapse or crack. As a result, the study said 300 out of every 100,000 people in the metropolitan area might be killed, while 1,100 per 100,000 people might be injured.

State seismologists have said the West Valley Fault is now ripe for movement, as they have studied its pattern and determined that it generates major quakes every 400 to 600 years. The last major quake from the fault was in 1658, or 366 years ago.

This event is what state seismologists refer to as the Big One, for which JICA, in its 20-year-old study, drafted a master plan for disaster response.

A 7.2-magnitude quake would send the entire NCR into Intensity 8 ground shaking under the Phivolcs Earthquake Intensity Scale, according to Phivolcs Director Teresito Bacolcol. People would find it very difficult to stand, well-built buildings would suffer severe damage and ground fissures would appear.

According to data from GeoAnalytics PH, a government platform that generates maps and assesses hazards and exposure, 92 out of every 100,000 Metro Manila residents are vulnerable to ground rupture, which could lead to large cracks or the collapse of paved roads.

For earthquake-induced landslides, two out of 100 residents, or 280,000 individuals, in the capital region are vulnerable to the hazard.

In addition to these threats, one of the most common yet overlooked hazards, especially in areas near bodies of water, is liquefaction.

Ground loose like liquid

Liquefaction is a phenomenon that causes the ground to become loose and act like liquid after a strong ground shaking, which could result in buildings and houses leaning or tipping over. In Metro Manila, liquefaction is predicted especially in areas facing coastlines and riverbanks, in the event of a strong earthquake.

Bacolcol said that this can lead to fissures, deformation, horizontal spreading of the ground, and sand boils or volcano-like vents that spew water.

“Buildings on these soil may sink or tilt, while buoyant structures like pipelines, tanks, and wells, could float,” he said.

The country’s chief seismologist said liquefaction will be limited to the lowlands facing Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay, and along the river banks and flood plains of the Pasig and Marikina Rivers.

According to our analysis, one of the most vulnerable areas is Pateros, the lone municipality in Metro Manila. The small town, bounded by Taguig and Pateros Rivers on the east, has a high potential for liquefaction.

In terms of the actual size of land, the City of Manila has the largest area in the capital region that faces a high risk of liquefaction, equivalent to 60 Rizal Parks. The capital city faces Manila Bay and is traversed by Pasig River.

Yolanda Reyes, 71, has been a resident of Pateros since 1979. Widowed in 2021, hers is a big traditional Filipino family with two children and eight grandchildren living under the same roof.

“My house is dilapidated. My husband was the one who built it over the years since he was a carpenter,” said Reyes in Filipino, as she described their two-story house.

The Reyes home was built with wood and concrete. It has been standing for more than 40 years. In the Philippines, many houses are built by local carpenters without the consultation with architects or engineers. This means that houses may or may not be up to code.

The Reyeses are among the over 60,000 residents of Pateros who face the risk of liquefaction, according to government data. Unfortunately, this number represents all residents of the town vulnerable to the impact of this hazard, with residents of Manila and Navotas closely behind.

Now in her senior years, Reyes said that Pateros is the home she had known for most of her life and will remain so despite the hazard.

She is aware of the risks. “We’ve been hearing about liquefaction,” said Reyes, an active senior citizen in her community.

The Phivolcs chief said the widespread liquefaction in Dagupan during the 1990 Luzon quake could also happen in Pateros should a magnitude 7.2 earthquake occur. There will be “severe and widespread effects including ground failure and building damage,” Bacolcol said.

Despite knowing this, Reyes said as much as she wanted to relocate, they could not. “Even if we wanted to move, we could not do it because we do not have enough money for that,” she said.

Many are vulnerable to liquefaction

In Metro Manila, four out of every 10 residents are prone to liquefaction. Of that four, three people face high risks for the hazard.

Among the cities in the capital region, the City of Manila has the highest number of people vulnerable to liquefaction. At least eight out of 10 residents live in these areas.

Bacolcol gave assurances that despite the risk, development can still continue in liquefaction-prone Pateros. Phivolcs recommends building structures that can withstand the hazard.

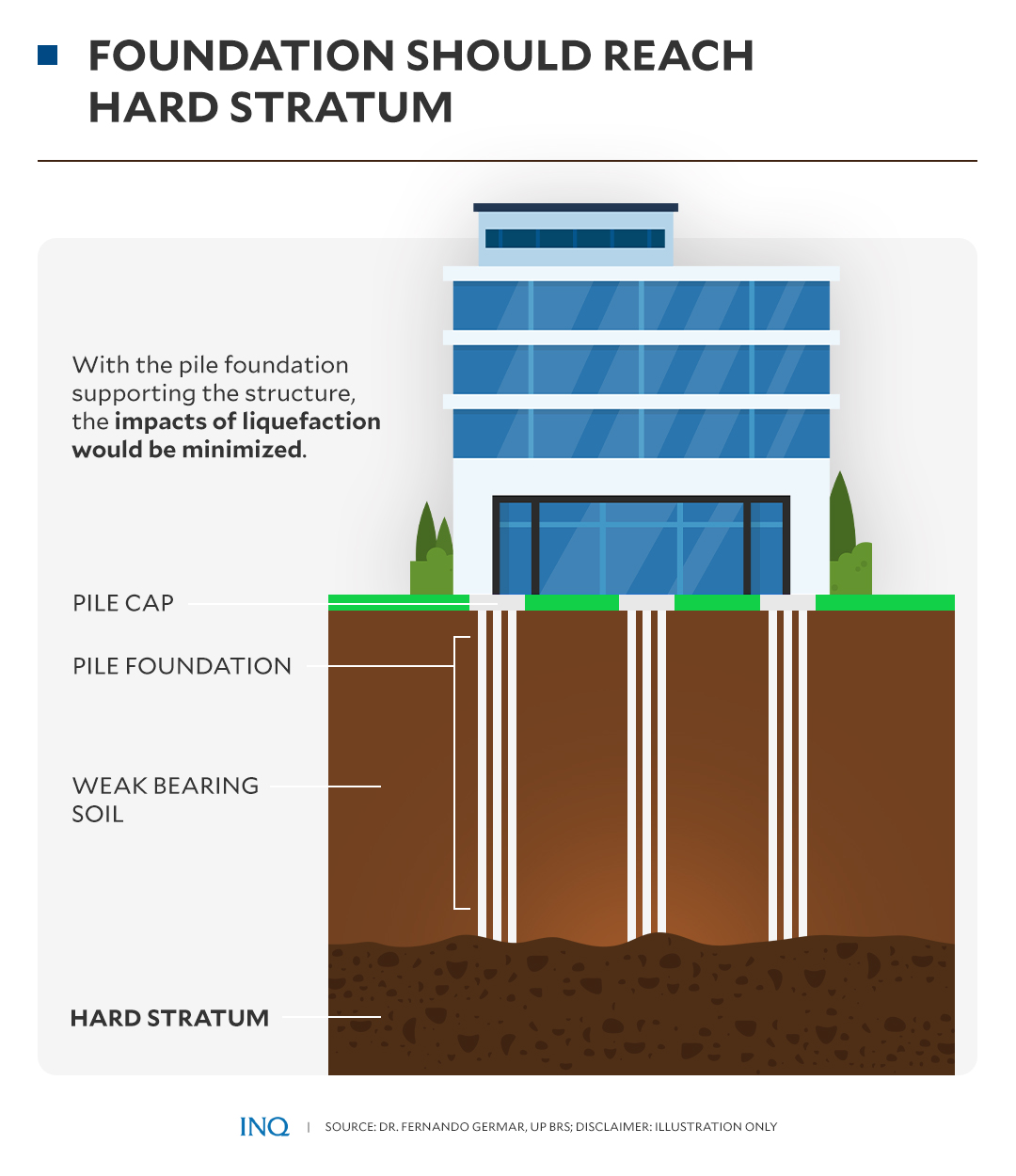

Engineer Fernando Germar, director of the UP Building Research Service, said that building a structure, especially high-rise ones, should focus heavily on the foundation to minimize impact. Germar is also a professor in structural engineering at the UP Institute of Civil Engineering.

“You could use a deep foundation, specifically pile foundations. The only requirement is the pile should reach the hard stratum,” he explained.

Stratum is the hard layer of sedimentary rocks beneath the earth’s surface. As emphasized by Germar, if the pile foundation reaches this level, it may prevent or minimize the threats posed by liquefaction.

Ponson also told INQUIRER.net that part of builders’ responsibilities is to conduct soil boring tests to analyze the type of soil on a site.

“From there, if we know that the bearing capacity of the soil is very poor, then there is a big possibility also that this soil, during a major earthquake, will [be prone to] liquefaction and will displace the structure,” he said. The worst case scenario is that the house might collapse as the soil loses strength to hold the structure in place.

Under the current building code, the government does not require regular inspections of residential houses. The government has left it to homeowners the task of checking their housers by using a questionnaire released by Phivolcs in 2014. An app and a web version were made public in 2023.

In April, the OCD appealed to the public to make sure that houses and buildings are up to code in preparation for the Big One, following the 7.2-magnitude earthquake that hit Taiwan.

“Engineering solutions and compliance with the building code are the best preparedness measures for earthquakes. We need to ensure that buildings and facilities are strong enough to withstand strong earthquakes,” said OCD Administrator Ariel Nepomuceno in a statement.

“Again, let us be reminded of the casualty projection for the magnitude 7.2 earthquake generated by the West Valley Fault. This is a very clear indication that there are a lot of things that we must do to advance our preparedness for earthquakes,” he added.

On a large scale, however, there is no telling just how many houses are vulnerable to earthquakes.

Critical facilities are at risk

Aside from homes, data also show that hundreds of schools and health facilities are built on ground prone to loose soil during earthquakes. The Philippine government, through a loan-funded project, will be retrofitting some of these.

A total of 265 elementary and high schools might be affected by liquefaction should a strong earthquake hit Metro Manila. At the top of the list is the capital Manila, where eight in 10 public schools in the city have a high risk of tipping over.

Even though Pateros is not at the top of this list, all of the five public schools in the municipality face this hazard.

At least 262 government and private health facilities are built on these high-risk zones. Manila remains the most at risk, where eight in 10 health facilities are built on liquefaction-prone areas, while all six of Pateros’ health facilities are vulnerable.

A total of 400 government buildings in Manila prone to earthquake-related hazards, including schools and health facilities, will be retrofitted under the Philippines Seismic Risk Reduction and Resilience Project (PSRRRP), through a $300-million loan with the World Bank.

According to the multilateral lender, the upgrades would adhere to the latest provisions of National Structural Code of the Philippines (NSCP), the state-approved referral code for the building code, which is drafted by an association of structural engineers.

In the project briefer, the multilateral lender noted that performance-based design is “not currently specified under the NSCP.” Performance-based design is an approach that focuses on designing structures to meet specific objectives, which involves assessing structures’ performance such as its ability to withstand earthquakes, for example.

It said: “[C]ompliance with the seismic provisions implicitly targets allowing building occupants to safely evacuate the building, thereby significantly reducing fatalities and severe casualties (but not guaranteeing that the building will be usable immediately after an event). In addition, compliance with the seismic provisions is expected to substantially reduce (but not entirely eliminate) the expected damage in the event of the design earthquake, which is within the range of Intensity VIII (associated with ‘The Big One’ scenario).”

In effect, the World Bank said structural upgrades will reduce building damage and potential deaths and injuries.

The retrofitting is expected to be completed by June 2026.

One amendment to Building Code in 20 years

To prepare for a strong earthquake, experts said part of the work is to properly enforce and develop regulations related to urban planning and the building code.

In fact, in the 2004 JICA study, this was listed as part of the “List of High Priority Action Plans.” Yet Congress has not acted. No one we spoke to for this investigation was willing to speak on the record about why legislation continues to be defeated.

According to a conference paper by Amarachukwu Nwadike, of Massey University in New Zealand, one of the primary reasons other countries regularly amend their building codes is to cushion the impact of disasters.

Hence, a code that has not been updated is a “disaster on its own.”

Despite the earthquake-related hazards in Metro Manila, legislators have passed only one measure to revise the 47-year-old building code, but it has yet to become a law.

In the last two decades, 37 bills have been filed to amend or repeal the National Building Code in the House of Representatives, averaging two bills each year since 2004. In previous Congresses, House bills aimed at amending the building code stalled at the committee level for an average of two years and six weeks, around two-thirds of the entire term of a congressman.

At the Senate, 15 bills have been filed since 2004. These stalled at the committee level for an average of two years and one month. No Senate bills amending the Building Code have been approved on plenary in the last 20 years.

In the current 19th Congress, the House was moved to update the Building Code, following the devastating Turkey-Syria earthquakes. It took only 11 months from the filing of the first House bill to the submission of the committee report and then the filing of the substitute bill.

The eight bills seeking to repeal the old Building Code were consolidated into House Bill (HB) No. 8500 or the proposed Philippine Building Act (PBA). This means that only one bill, HB 8500, has successfully passed the final stage of the legislative process in the House since 2004. It isn’t a law yet, though.

The Senate version of the bill has yet to be passed and has remained pending at the committee level since the last public hearing on Mar. 8, 2023.

The Senate needs to pass its version first, sort out any differences with the House, if any, then that would be the time it reaches Malacañang.

With the passage of the House version, it is now in the Senate's court.

1977 Building Code vs bill

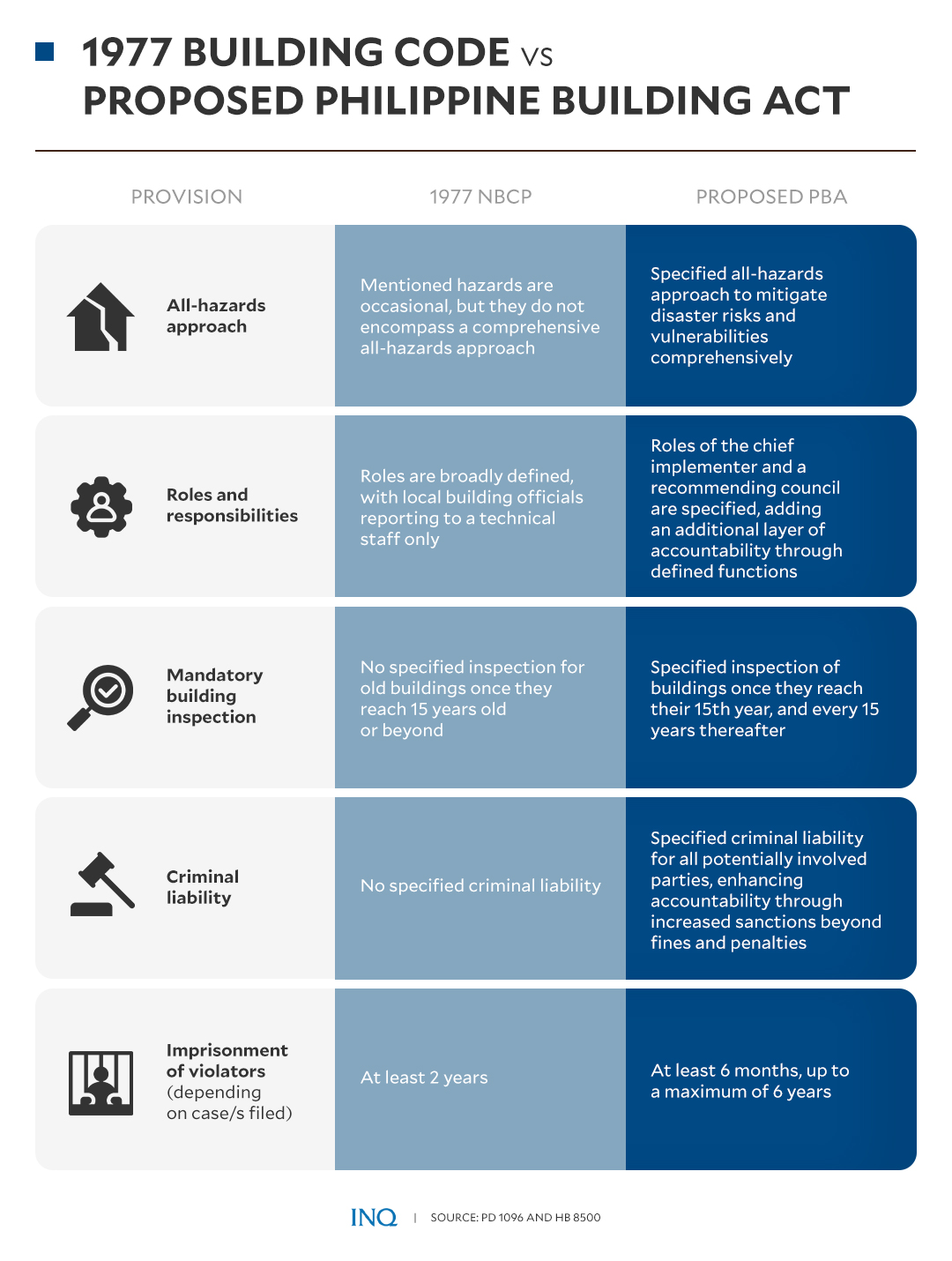

Several key provisions to manage disasters were either incomplete or absent in the current 1977 Building Code, unlike in the proposed PBA.

The proposed measure aims to correct and improve upon various aspects, including minimum standards and building classifications, particularly addressing issues related to earthquakes and corresponding hazards.

Even though the implementing rules and regulations were last updated in 2005, the current Building Code is still notably outdated, not just concerning disaster risk reduction but also in terms of accountability among owners, officials, and professionals.

One of the most important provisions in the proposed PBA is the adoption of an all-hazards approach in building construction.

The bill defined this as “a comprehensive and coordinated approach in taxonomy and characterization of hazards, both natural and human-induced.” This means that when building a new structure, it must be built to withstand a disaster.

It further defined it as “an approach in risk assessment and emergency planning such that the full range of potential threats are identified, associated exposures, vulnerabilities, and risks are mitigated, assessed and ranked, and emergency plans are imbued with elements that are shared among multiple hazards and elements that are unique to some.”

Another major difference between the existing code and the proposed PBA is the specific role of the public works secretary as chief implementor of the new code with the title national building official.

The secretary is tasked with ensuring the faithful execution of all laws related to building design and construction, serving as the proposed PBA chief implementer.

In the building code’s latest IRR, local building officials report solely to the National Building Code Development Office, which is a part of the technical staff of the public works secretary.

In the PBA bill, the Office of the National Building Official will be established to oversee all matters related to building construction, with assistance from the Building Regulations and Standards Council which would be formed if the bill becomes a law.

This council will be composed of representatives from the public works, housing, fire, environment, and science and technology departments, among others. It will oversee updates to existing rules and regulations, as well as the implementation of "referral codes," which, under this proposed law, will be referred to as "reference standards.”

The specification of roles and defined functions of officials are crucial, as these will determine responsibilities, not only the line of authority but also accountability.

The proposed new building law also mandates stability inspections, commissioned by the building owner, to assess hazards for structures 15 years or older. Inspections would be done every 15 years. This key provision is absent in the 1977 Building Code.

The proposed measure would also mandate the creation of a national database of permits and other data about all buildings and structures, including reports on maintenance, inspections, and assessments.

The information in this database would be used by national and local agencies for disaster management. Any information that would be made available to the public would be subject to the provisions of the Data Privacy Act.

The penalties and corresponding fines were also specified for violators different from the current code where penalties are broadly mentioned. Although fines and penalties were included in the existing implementing rules, they were mentioned in a limited manner.

In cases of gross violation, the PBA bill empowers the public works secretary, as National Building Official, and its local counterparts to file criminal charges against violators, a feature absent in the existing code and which adds significant accountability for building structures.

False certification during inspections to approve building permits and the use of materials that do not conform to standards are among the prohibited acts.

These unauthorized acts, which might incur fines, penalties, or even jail time, apply specifically to violating building officials, professionals, contractors, certifiers, structural peer reviewers, inspectors, testing laboratories, and even building owners themselves.

The proposed PBA stalls at the Senate

Senator Ramon “Bong” Revilla, chairman of the Committee on Public Works, told INQUIRER.net they are considering the House version in the committee discussions, as there are several other bills filed in the Senate, and they are taking all of these into consideration.

"We are working speedily but not hastily. We are endeavoring to submit a report soon, but that is not to say that we will be rushing it. The Building Code is a very technical document that needs diligent and careful study," Revilla added.

The actor-turned-politician said that his committee is open to receiving position papers, technical opinions, and other recommendations regarding the proposed PBA.

"While we recognize that the code is decades old, we also acknowledge the fact that the various professionals have their own codes to utilize. And these codes are being periodically updated to be in keeping with the current developments and advancements,” he added.

Revilla was referring to Referral Codes or the complementary standards that are guided by an overarching law. The NSCP, which is regularly updated by the Association of Structural Engineers in the Philippines (ASEP), is a referral code guided by the Building Code.

As a non-government professional organization, ASEP publishes the NSCP with the approval of the DPWH chief.

NSCP and other referral codes, like the Fire Code of the Philippines and the Philippine Electrical Code, are updated periodically.

On top of these codes is the IRR of the building code, which was last updated in 2004 and took effect on May 1, 2005.

This is why for Revilla, the government should prioritize the proper and effective implementation of the building code, as some provisions, based on his committee’s observations, do not actually need amending.

But renowned urban planner and architect Felino Palafox Jr. said that amending the building code is an urgent matter that needs immediate action. In an interview with INQUIRER.net, Palafox lamented that he and his firm Palafox Associates have been submitting recommendations to prepare for disasters to sitting presidents and the Congress.

“Every time there’s a big disaster in our part of the world and the rest of the world, we send recommendations,” Palafox said.

“The last president, even the current president, we sent 145 recommendations to address earthquakes, tsunamis, storm surge, flood control, earthquakes, landslides, fire, [and] lessons from Ondoy flooding. We gave several recommendations. We know the problems, we know the solutions,” Palafox said.

The architect noted that in other parts of the world, governments were quick to implement reforms in their building or structural codes after a disaster.

Asked if private interests block the PBA and if legislators lack the political will, he avoided giving categorical answers. Other experts and groups interviewed for this report declined to comment on lobbying efforts to block the bill.

“Why is it (implementing recommendations) being delayed? Is it true that more money is being captured when it’s state of calamity (sic), whereas addressing the hazards before the disasters [is] 90% less expensive?” Palafox said.

“I think you know that (about political will). How come our recommendations since the mid-1970s were not yet implemented? I said that when I was 26 years old. I think the catastrophic traffic, flooding, [being] not prepared for disasters is happening now that I’m 74 years old,” he said.

The significant difference, according to him, lies in the fact that in other countries, they listen to experts. “I already have [been to] 40 countries and they listen. They listen and implement.”

Urgent update needed

Similar to Palafox, Germar also emphasized the urgency of enacting measures to amend the building code, especially in light of the recent earthquakes in Abra, Surigao del Sur, and Davao Occidental.

“What we’re actually considering is just revising the IRR of the building code. However, upon review and consultations with different stakeholders, it became evident that many provisions need to be changed,” said Germar.

Germar agreed with Revilla that it would take decades to amend the law. He also acknowledged that it might be easier to amend the technical provisions of the building code by consensus among professionals.

However, Germar pointed out that it will be more challenging if only the implementing rules are revised. “It will be harder if the IRR is the only one revised because it might become tangled. So it’s better if the entire law is changed,” he said.

The Phivolcs chief shared the same sentiment.

"Of course, it would be better to use more recent information that we have to craft our policies,” Bacolcol told INQUIRER.net.

As a child who grew up drawing houses and buildings, Ponson said that the collapse of his paternal family’s home at Ruby Tower decades ago pushed him partly to pursue architecture.

“Due diligence is the lesson for all of us, architects, and civil engineers,” he said.

But for thousands of construction and design professionals like him, due diligence could not be fully optimized when the very law that guides them is not only outdated, but also not responsive to the needs of the times.

Regardless if the people are prepared, if the provisions of the law are deemed obsolete and its implementation is deemed lenient, Metro Manila will remain in a more vulnerable state as it sits on top of a ticking bomb that’s just waiting to explode.

(Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy, a program of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi)

All quotes were translated into English.

- Story by: Samuel Yap

- Story Mentor: Aika Rey

- Data Mentor: Thet Win Htut

- Editor: Eva Constantaras, Aika Rey, Tony Bergonia

- UX/UI Lead: Joseph Garibay

- UX/UI Designer: Kristine Sinamban

- Additional Graphics: Samuel Yap

- Additional Photo: Marianne Bermudez / PDI

Methodology

The author of this report sourced data from government agencies and the legislative branch. Demographical and institutional exposure data on hazards like liquefaction, earthquake-induced landslide, and ground rupture were obtained through GeoAnalytics PH, a portal under Phivolcs.

Data on deaths, displacement, and damage caused by earthquakes in the last 30 years were from the OCD. The number of building code related bills and their legislative status were from data collected from official sites of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The findings of these analyses were consulted and discussed with experts from Phivolcs and the UP Building Research Service, the research and extension arm of the Construction Engineering and Management and Structural Engineering Groups of the UP Institute of Civil Engineering.

The author also reached out to a survivor-descendant of the Ruby Tower collapse, as well as residents of the municipality of Pateros, the most liquefaction-prone area in Metro Manila. For transparency, readers can view the datasets and analyses here.