DOJ studying PH reentry to ICC, other legal options

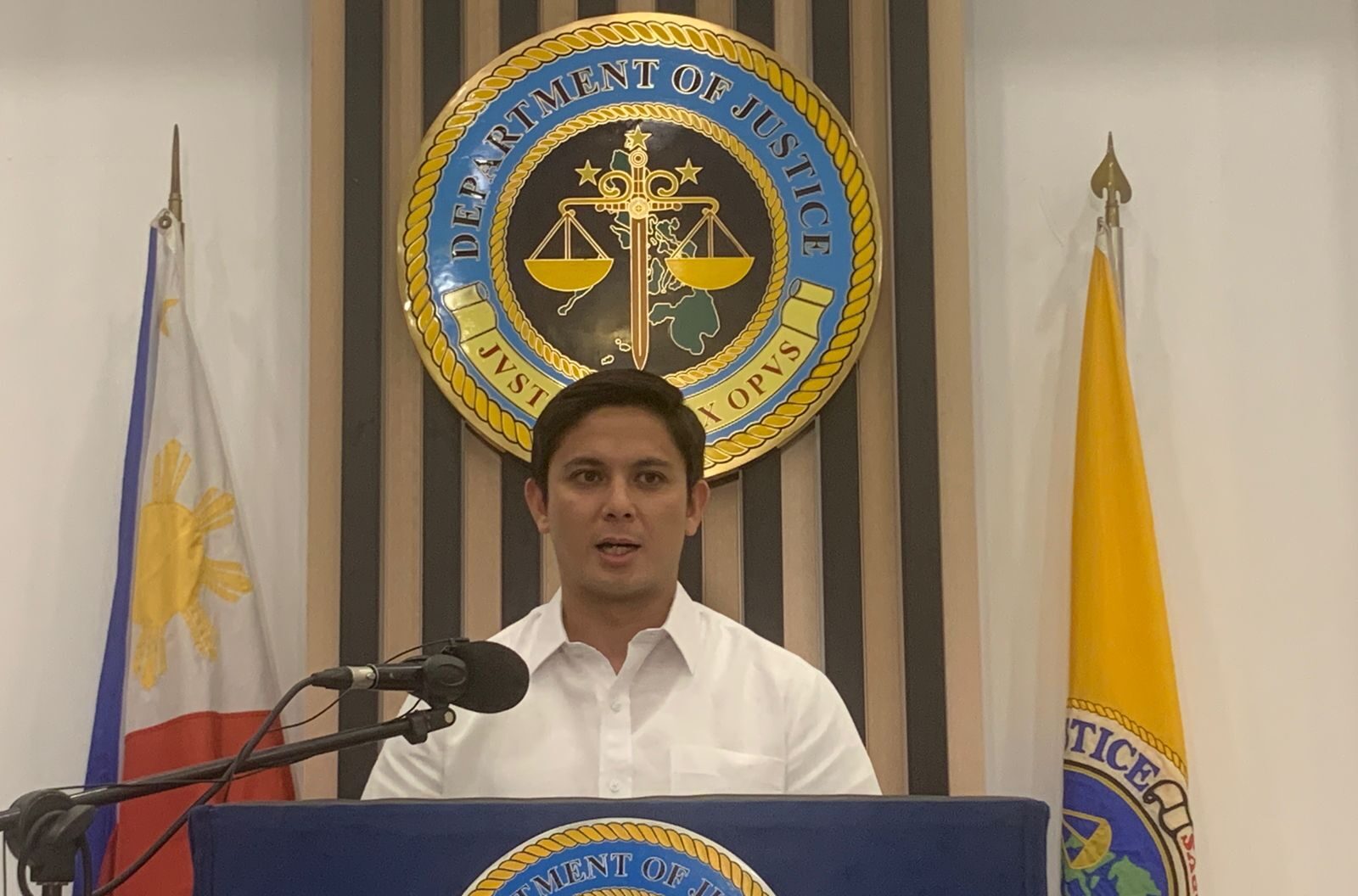

DOJ Assistant Secretary and spokesperson Jose Dominic Clavano INQUIRER.NET FILE PHOTO/TETCH TORRES-TUPAS

MANILA, Philippines — After making adamant declarations that the Philippines would not cooperate with the International Criminal Court (ICC) in arresting former President Rodrigo Duterte, the Marcos administration is still preparing for “all legal options,” including returning to the Rome Statute, the 2002 treaty that established the court, a justice official said.

Assistant Justice Secretary Jose Dominic Clavano IV on Wednesday said the legal brief being prepared would be an “objective statement or an analysis of the pros and cons of each option” to guide President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. on “how he will move.”

“Once the ICC warrants of arrest, if ever, are issued, then he will know what the legalities are, his options, and the President’s remedies,” the Department of Justice (DOJ) official said in a press briefing.

READ: Trillanes: ICC expected to issue arrest warrant vs Duterte by June or July

Article continues after this advertisementClavano later told reporters in a message that the legal brief would be done “with an awareness that policy frameworks may evolve.”

Article continues after this advertisementClavano clarified that the government’s stance of not recognizing the ICC’s jurisdiction in the country did not change.

“Nonetheless, we have an awareness that it could change. And we have to be prepared for all of this. We are the Department of Justice and as any legal team would tell you, you really have to consider all the options. You have plan A, you have plan B, all the way to Plan Z,” he said.

“We don’t want to clip the President’s options.”

READ: Challenges ahead for ICC ruling

‘Warrants out soon’

Clavano made the remarks after former Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV said on Tuesday that the ICC would soon issue a warrant of arrest against the former president and others in relation to the investigation of crimes against humanity in Duterte’s bloody drug war.

Despite its lack of information on when the ICC might order Duterte’s arrest, Clavano said the DOJ is already studying the legal aspects, including the “possible reentry into the Rome Statute.”

“That’s all included — what are the implications of staying out, what are the implications of going back, what are the legal obligations that may arise — all of that. As well as the arrival of possible, or alleged, ICC warrants of arrest, that is also included in the legal briefer,” Clavano said.

He said Marcos had long ordered the DOJ and the Office of the Solicitor General to study the possible legal issues.

Earlier statements

Speaking to reporters on Jan. 23, Marcos declared that his government would not help the ICC investigators.

“Let me say this for the 100th time. I do not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICC in the Philippines. I consider it as a threat to our sovereignty, therefore, the Philippine government will not lift a finger to help any investigation that the ICC conducts,” the President said.

“We do not recognize your jurisdiction,” he added, addressing the ICC. “Therefore, we will not assist in any way, shape or form, any of the investigations that the ICC is doing here in the Philippines.”

In a statement on the same day, the DOJ repeated its earlier position that having withdrawn from the ICC in 2018, “the Philippines has no legal duty to comply with any obligations or proceedings thereunder.”

Prior consent

According to the DOJ, any presence of international bodies like the ICC within the Philippines must follow the Constitution and relevant laws.

Specifically, it said that prior consent and approval from concerned agencies like the Department of Foreign Affairs, the Department of the Interior and Local Government, and the DOJ itself must be secured before the foreign entities conduct official business in the country.

The DOJ acknowledged the 2021 ruling of the Supreme Court that Duterte could not invoke the withdrawal from the Rome Statute to evade the investigation of the ICC on his alleged crime against humanity in the war on drugs when the Philippines was still a part of the ICC.

However, the DOJ pointed out that the ruling was merely the “court’s incidental expression of opinion” which did not establish a “precedent.”

“As a sovereign nation with a robust and functional justice system capable of addressing internal issues without external interference, the Philippine government has shown that it is ready, willing, and able to investigate and prosecute any crime committed within its territory,” the DOJ said.

How it began

Lawyer Jude Sabio in April 2017 filed a complaint before the ICC regarding the alleged extrajudicial killings when Duterte was the mayor of Davao City.

Two months later, Trillanes and Rep. Gary Alejano filed a “supplemental communication” before the ICC on Duterte’s drug war.

On Feb. 8, 2018, Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda of the Office of ICC launched the preliminary evaluation of the atrocities allegedly committed in the Duterte administration’s antidrug operations.

Only a month after, the Philippines announced its withdrawal from the ICC as Duterte claimed that the country was never a state party to the Rome Statute because there was no binding document, particularly the publication of the treaty in the Official Gazette, that indicated the court’s jurisdiction.

Positive development

According to lawyer Kristina Conti, assistant counsel for the drug war victims, the DOJ’s move to prepare a legal brief is a “positive development” and a “win-win” situation, coming from a “worst-case scenario” during Duterte’s term when he refused to cooperate or pledge any support to the ICC.

She said the DOJ’s legal brief could tackle different concerns, including the parameters of cooperation in the ICC’s investigation, Manila’s cooperation in implementing the warrant, as well as the country’s “engagement” with the tribunal.

In implementing the arrest warrant, Conti said the legal brief could cover “possible pressure points or trigger points” if the authorities would cooperate.

“Another issue could be in the engagement. The word he [Marcos] used before was ‘disengage,’ completely disengage. That’s another word altogether because it meant that they will not cooperate,” Conti told the Inquirer in an interview.