Enrile says ‘no regrets, no mistakes,’ as he turns 100

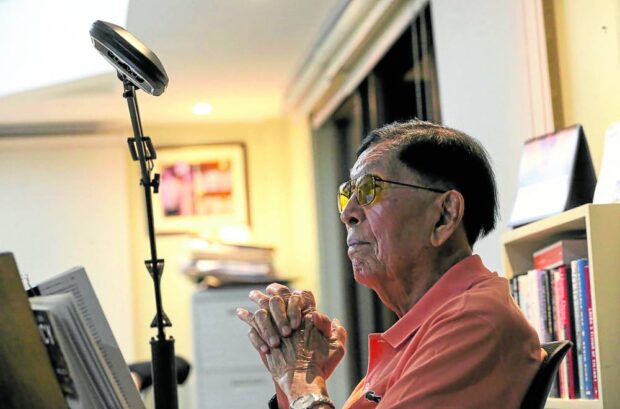

FULL LIFE | Juan Ponce Enrile, the former defense chief and Senate leader, says: “Whatever I did in all my years in government, as well as outside, I did them with full knowledge and complete planning.” (Photo by LYN RILLON / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

MANILA, Philippines — On any given workday, this government lawyer dresses up for the office, pores over piles of paperwork, and attends meetings like any other ordinary worker.

Actually, he’s far from ordinary, having stayed in public life for six decades, with his own political highs and lows but never out for long, taking different shades but never really fading.

Until the twists and turns of Philippine history put him back where he started: a seat in the president’s power circle.

But this time around, his office in Malacañang has an easy access to an elevator—as he requested—because his knees could no longer negotiate the Palace stairs.

“I could not walk the stairway of Malacañang anymore,” Juan Ponce Enrile told his recruiter back in 2022 when first offered the job.

Article continues after this advertisementAt 100, the chief legal adviser of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. might well be the world’s oldest government employee, one who has outlived the likes of Queen Elizabeth II, Henry Kissinger, and KathNiel, based on memes circulating on social media.

Article continues after this advertisementToday, Juan Valentin Furagganan Ponce Enrile, so named because his birthday fell on Valentine’s Day, marks a full century of existence, still active in public service after a storied career that has spanned six decades.

Enrile sat down with the Inquirer on Saturday afternoon at his residence in Dasmariñas Village in Makati City, one of the country’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

Wearing a tangerine shirt, he sat at the head of a white conference table and gamely replied to questions. His daughter, Katrina Ponce Enrile, administrator of the Cagayan Economic Zone Authority, sat on his right flank, taking down notes.

‘Tell me a country’

Enrile talked about his obsession with reading as a key secret to maintaining a sharp mind even at his advanced age.

“When I got out of the Senate in 2016, I did nothing except study all those books,” he said, pointing to a bookshelf that stood beside his desktop computer.

“I kept reading, so modesty aside—tell me a country and I will discuss it with you—its geography, strengths and weaknesses, its problems,” he said.

These days, Enrile is busy with finance books written by bestselling American author James Rickards, including “The Death of Money,” “The Big Drop” and “The New Case for Gold.”

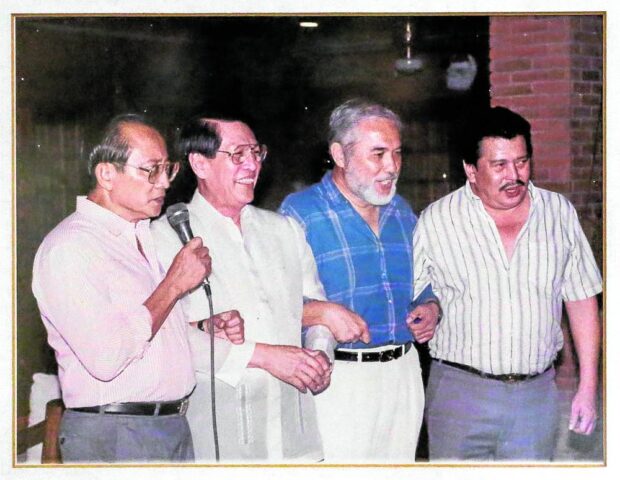

POWERFUL ALLIES | Juan Ponce Enrile during his Senate heyday (second from left), joined by friends and allies former President Fidel Ramos, former Speaker Ramon Mitra and former President Joseph Estrada. This is among the photos displayed in his Dasmariñas Village home. (Photo courtesy of Enrile)

Serving a Marcos again

According to his house staff, Enrile loves regular morning walks around his grass lawn for his daily dose of sunshine.

Many thought Enrile would gradually fade into the sunset after he completed his tenure as Senate President in 2016. But he was plucked from retirement when Mr. Marcos assumed office as the country’s 17th president two years ago.

Enrile said he did not have to apply for his job, recalling one night in July 2022 when he got a call from then Executive Secretary Victor Rodriguez, who asked if he would be willing to join another Marcos Cabinet. He hesitated at first, he said, but eventually decided that taking on another high-profile job was a no-brainer.

“I had nothing to do. It was only [for the chance] to be of service to the country again,” Enrile said.

In some ways, serving in Mr. Marcos’ Cabinet represents life coming full circle for Enrile, considered by some as a hero and others a villain during the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution that toppled the regime of the President’s late father and namesake.

1972 ‘ambush’

On Sept. 22, 1972, then Defense Secretary Enrile and his convoy were supposedly ambushed in Wack Wack Village in Mandaluyong City — an “event” that set the stage for the declaration of martial law by the older Marcos a day later.

It was only in 1986, when he and then Lt. Gen. Fidel V. Ramos announced their revolt against the dictator, that Enrile said the ambush had been staged—an admission he repeated several times in other interviews through the years.

But in his book “Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir,” published in 2012, he revised his own history, claiming that the ambush had been real.

“This [staged ambush] is a lie that has gone around for far too long such that it has acquired acceptance as the truth…. This accusation is ridiculous and preposterous,” he wrote.

Despite that “sad episode,” Enrile said there was no bad blood between him and the Marcos family, as he had made sure of their safe exit from Malacañang at the end of that uprising.

“Many people misunderstood my relationship with this family; [Edsa People Power happened] because there was this junta already planning to take over the government,” he claimed, alluding to the bickering within Marcos’ inner circle at the time, which, he said, forced him to form his own group.

In the Senate

Enrile continued as defense chief, this time under Marcos’ successor Corazon Aquino. But his increasing criticism of her government, amid the coup attempts that were linked to Enrile’s allies in the military, prompted her to fire him. Aquino would continue to deal with that threat until 1989.

By 1987, with the country under a new republic and constitution, Enrile threw his hat into the senatorial arena and led the Senate through its now historic chapters—some of these, proud moments for the chamber (the vote to remove the US bases in 1991), others controversial (the impeachment trial of President Joseph Estrada in 2000).

While he was senator, Enrile also ran for president in the general elections of 1998, but lost to Estrada.

His support for Estrada, who was impeached in 2000 and ousted the next year by another popular uprising, cost Enrile his reelection bid. But he returned to the Senate in 2004 and went on to complete two terms, becoming its oldest Senate President in 2008.

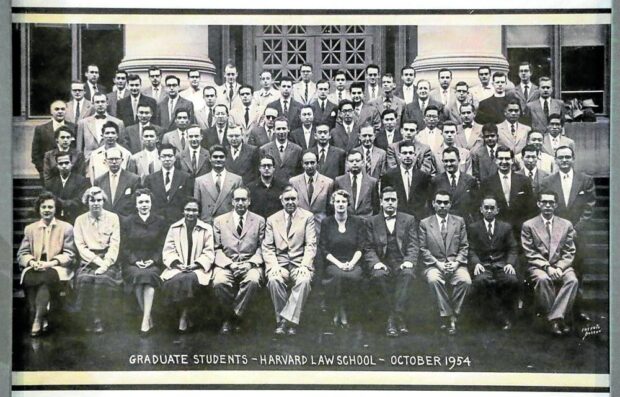

FOREIGN EDUCATION | Graduate students of Harvard Law School in 1954. Juan Ponce Enrile is seated at the front row, extreme right. (Photo courtesy of Enrile)

‘A very simple life’

In 2013, Enrile and two other senators were implicated in the pork barrel scam for allegedly funneling P172 million of his Priority Development Assistance Fund to bogus nongovernment organizations. He was detained in 2014, but released on bail after a year.

He is still battling plunder charges in the Sandiganbayan.

Enrile said his struggles early in life, in his native province of Cagayan, steeled him for the difficult challenges ahead.

“I knew what it is to be poor, to be a lowly person, to be abused; I used to be called a bastard. I was a houseboy. I cooked, cleaned the asses of the children of my bosses, washed the clothes of my benefactors,” he said.

These days, on top of his salary, which he wouldn’t disclose as “it’s public record,” he sustains himself with a “little pension” from his daughter Katrina, who used to run the family’s Jaka Group of Companies.

But he doubts that the government will bestow on him the P100,000 cash incentive for 100-year-olds under the Centenarians Act, according to Katrina.

“My dad lives a very simple life. He says he has enough T-shirts and is comfortable with his life as he has always been,” she said.

‘No perfect government’

Enrile said the infighting between the Marcos and Duterte families is par for the course. “That’s normal; there’s no guarantee that everybody is good because even in heaven, you have Lucifer,” he said

“The trouble with us is that we are thinking that there is a perfect government—there’s no such thing,” he said.

Despite the controversies and scandals in his long career, Enrile said he has no regrets about decisions that have shaped the country’s history, for good or ill: “Whatever I did in all my years in government, as well as outside, I did them with full knowledge and complete planning.”

READ: JPE’s not-so-secret path to longevity

“But one thing I can tell you: I never ordered anybody to be killed. I don’t kill people, not even by any means. I charge them if I have to charge them but I never ordered,” he said, his voice rising.

As for mistakes, Enrile counted zero in all of his 100 years: “If I did, I would be dead by now.”