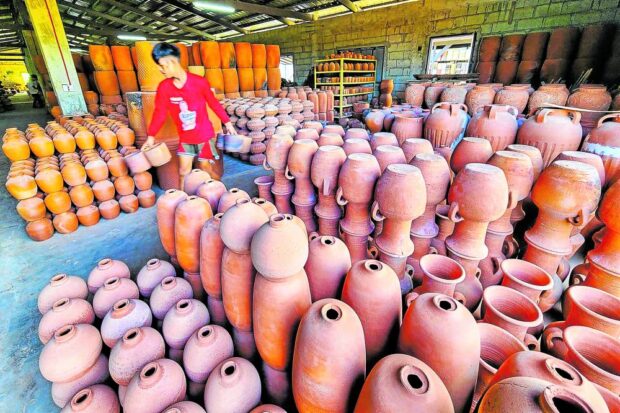

LEGACY | Pampanga Pottery in Sto. Tomas, Pampanga, offers a visual feast of the rich artistic heritage of Kapampangan potters belonging to generations of skilled craftsmen. (Photos by WILLIE LOMIBAO and RAY ZAMBRANO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

STO. TOMAS, Pampanga, Philippines — For generations, residents of this town, the smallest in Pampanga province, have been creating pots, locally known as “pasu” or “masetas.” They do this not only to sustain the needs of their families; for most of them, it is a way of life.

Families working together in their “backyard factories” or pottery shops are a usual sight in some villages in this town. Residents would get involved in the art of pottery at a very young age.

Before the pandemic struck in 2020, local pottery production was already considered a dying industry, says Precious Quiambao Garcia, 34, who inherited a pottery business from her parents.

Despite the challenges, she has found a way to keep the enterprise afloat.

Garcia, founder and owner of Pampanga Pottery, recalls how she resented the pottery business because she felt that the workers were being exploited.

“They (workers) are always sweaty and tired but they are not valued that much. It even came to a point that their wages no longer matched their skills,” she tells the Inquirer in a recent interview.

Garcia cites this reason for her hesitance when her father asked her to be involved in the business.

After overseeing the work that potters do, hearing their stories and meeting their families, she realized that many people depend on their business to survive. This eventually changed her decision.

The pottery industry in the town is a testament to the resilience of the tradition that has endured a string of challenges, including the pandemic.

Family affair

Garcia’s father, Emmanuel Quiambao, 57, has been a potter at a young age.

“My father used to tell us that he helped sun-dry the pots along the road when he was a grade-schooler,” Garcia says.

Her father worked in pottery until he became supervisor and manager of Art of Clay, formerly Terracotta Artwork, that exports pots.

“Pottery really gave my parents a break. Since our family has a good relationship with the exporting factory where my father worked before, we are now their subcontractor,” Garcia shares.

Her father now oversees their workers as production manager of their pottery business.

The bulk of their production, where 90 percent of their income comes, is exported to the United States, Australia and the Middle East.

“It’s ironic that other countries are looking for our pots, but our local market wants Vietnamese pots. Actually, we can compete against Vietnam but we have to mark our territory so that we can match the quality,” Garcia laments.

HANDCRAFTED A worker prepares her station so she can start shaping clay into a handcrafted pot. —WILLIE LOMIBAO

READ: Public safety, access sought in P225M Pampanga road project

READ: Hukbalahap monument unveiled in Pampanga

READ: Armed men rob Japanese restaurant, customers in Pampanga

Giving back

“The business is doing okay,” says Garcia, but she notes that the real challenge is how they will boost the local market, and make them appreciate the art and not only see pots as a commodity.

According to Garcia, the real threats to the industry are plastic manufacturers and imported pottery.

“But for me, I no longer see it as a source of income; I no longer see it as a business. It seems that it has become the responsibility of our family to help our workers and their families who rely on pottery,” shares Garcia.

If the industry booms, it would greatly benefit local communities. “Residents do not need to find livelihood elsewhere because there is an opportunity within their homes,” she says.

Many potters in Pampanga are just living within their communities, allowing them the freedom to still do household chores in between work hours.

“The mothers who work with us can easily go home. They usually come to work at 6 a.m. then go back home to prepare breakfast for their children. They will return to work and then leave again at 10:30 a.m. to prepare their lunch. We also allow them to bring their babies. They will just bring a pillow and they can breastfeed their baby at work,” Garcia says.

Aside from her involvement in the pottery business, Garcia is also an advocate for the use of other handmade and environment-friendly products.

“When I saw the production of pots, it was not difficult for me to love it because it does not use any material that is toxic to the environment. It was aligned with my advocacy to reduce our carbon footprint. I don’t want plastic waste; I don’t want fancy things,” she says.

“So that’s when my involvement in pottery deepened. I did my research, and I became interested in the history of pottery in Sto. Tomas and even outside the Philippines.”

Pottery in Sto. Tomas is now able to adapt to new technology. It is a mixture of modern and traditional, but business owners are now teaching tourists, mostly students, the traditional way of doing pottery so this knowledge, they hope, will help them become good consumers in the future.

“Hopefully, our efforts today will bear fruit, and for the children we teach who will become consumers after 10 to 15 years, I hope they will choose to buy pottery instead of plastic; that is really our end goal, and eventually, the generation will realize that [pottery] is not only someone’s work but also a form of art,” Garcia says.

While visiting Pampanga Pottery’s showroom and production area, tourists will have a chance to witness local artisans at work, and try their hand at pottery through the help of three instructors and seven skilled workers.

Pampanga Pottery opened in January 2020, two months before the implementation of lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“For me personally, I thought it was not for me because it’s a sign that we just launched [the business] and then this is what happened. I was discouraged during that time,” Garcia says.

But after two years, when health and travel restrictions started to ease, the business started picking up, thanks to social media.

From less than a hundred likes on the business’ Facebook page, it spiked to 14,000 likes as “plantitos” and “plantitas” (plant enthusiasts) started building their collections, Garcia says.

MUDAND ART Master sculptor Willy Layug (second from right) guides local potters through a process of incorporating art into their creations. —RAY ZAMBRANO

Collaboration

Pampanga Pottery has collaborated with Kapampangan master sculptor Willy Layug to incorporate pottery into the work of sculptors and blacksmiths in Apalit town, and the “pukpuk” (metalcraft) industry in Floridablanca town. The program is headed by Lingap Kapampangan.

“Sir Layug wants to do it yearly, but my advice to him is to do it at least once a month to achieve continuity,” Garcia shares.

The first session was held in October and the second session will soon be held to finish their products. In December, all artworks produced through this collaboration will be exhibited at the Sinukwan Festival.

According to Garcia, this is just the beginning of their bigger vision of collaboration with different artisans in Pampanga.