Chinese grads hold off career goals, take gov’t jobs

BEIJING/HONG KONG — Having failed to find his dream job at an internet company upon graduation, Peter Liu settled for a role in a state library where there is so little need for his participation that he spends his time studying for a change in his career path.

“It’s really hard to get work at big companies,” said the 24-year-old who majored in TV production at a Beijing university before moving back home in the central Henan province.

Liu got the librarian job after a government-led campaign to secure temporary work for graduates.

Wang Jun, chief economist at Huatai Asset Management, said temporary jobs are “a short-term fix for stability, to relieve social conflicts brought by joblessness.”

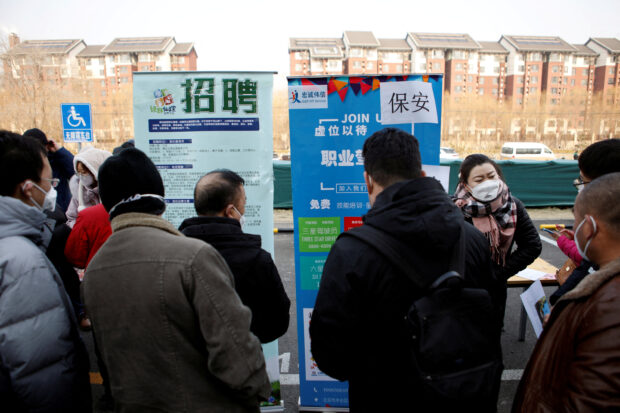

Such “welfare jobs,” as they are known in China, include roles as receptionists, office administrators, security guards, and community workers.

Article continues after this advertisementVarious government institutions offer such jobs every year, but they usually draw applications from disadvantaged groups, such as the elderly or persons with disabilities.

Article continues after this advertisementThis year, amid a deepening youth joblessness crisis in the world’s second-largest economy, even remote rural positions have seen intense competition from young Chinese with diplomas from top universities.

The government sees employment as key to pacifying China’s most pessimistic generation in decades, while graduates gaining even limited work experience can also benefit their future employers if the economy recovers, analysts say.

Omitting data

The one-to-three-year contracts pay roughly the minimum wage in the region, typically between 2,000 and 3,000 yuan ($275-$412) per month, sometimes including free meals.

This is much less than the average expectation for a first job salary of 8,033 yuan, according to a survey by Chinese recruitment firm Liepin.

A separate program aiming for 1 million internships this year has courted state-owned and private firms for participation.

The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, which did not reply to a request for comment on the government programs or the job market, told state media last week youth employment was improving.

China has in the past year eased some regulatory burdens on tech, property, and finance firms — traditionally large employers of new talent. But state media editorials have also encouraged young graduates to take lower-skilled jobs.

On Wednesday, the statistics bureau is expected to omit for the fourth consecutive month the release of youth unemployment data, suspended in July after reaching a record 21.3 percent in June, just as 11.6 million graduates were entering the job market.

Using the slow days

The total takeup of short-term jobs and internships remains unknown. But social media posts commenting on the selection process and discussing career options are frequent, and analysts expect such roles will be in demand in a slowing economy.

The state sector—which provides a fifth of the urban jobs in China—can only temporarily alleviate economic pressure for a portion of university graduates through such campaigns, economists say, warning youth unemployment remains a major long-term headache for Beijing.

“Youth unemployment will stay with us for quite a long time, at least for five to 10 years,” said Wang.

Liu never expected to go for a public sector career, but for now, he is at least happy that he can take that chance.

“I don’t want my parents to see me staying at home all day with nothing to do,” he said.