As Baguio turns 114, ‘Cha-cha’ talks continue

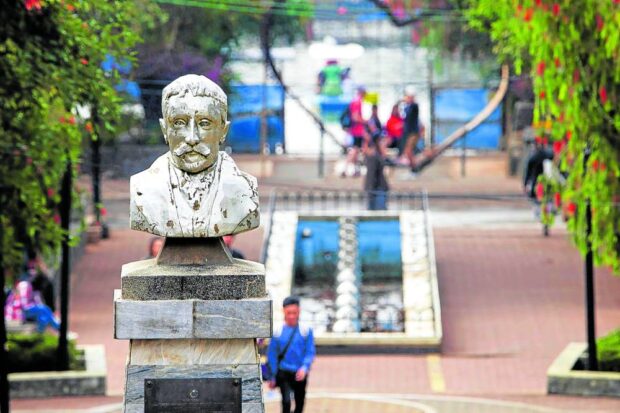

MANBEHIND THE PARK Baguio City celebrated its 114th Charter Day on Sept. 1 to commemorate its opening as a chartered city by the American colonial government. The summer capital was

designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, after whom BurnhamPark was named. His bust nowstands guard over his creation. —NEIL CLARK ONGCHANGCO

BAGUIO CITY—The city celebrated its 114th foundation day on Friday, and its lone representative to Congress used the occasion to describe the city’s 1909 charter as the document that empowered Baguio to govern itself and shape its future.

The American colonial government opened Baguio as a chartered city on Sept. 1, 1909, after commissioning Chicago architect Daniel Burnham to design what would be America’s first hill station, a health sanctuary in the mountains of Benguet province.

“Charter Day is more than just a celebration. It is a declaration of our city’s identity, rights and responsibilities,” said Rep. Marquez Go in a speech during Baguio’s commemorative program.

The 1909 charter was enacted through Act No. 1963 and was penned by the late Supreme Court Justice George Malcolm. Last year, however, it was revised by Congress through Republic Act No. 11689 which has been criticized by some local officials and groups in the city.

Go said Baguio’s Charter Day is also “a commemoration of the day we were officially recognized as a distinct and thriving entity empowered to govern ourselves, make decisions and shape our own destiny.”

Article continues after this advertisementHe said residents must display “a sense of pride and gratitude for our past, a determination to shape our present, and an unwavering commitment to the future.”

Article continues after this advertisementDeliberation

But earlier this week, the city council continued to deliberate on possible charter changes (Cha-cha) after criticizing the law for supposed flaws that might disrupt local governance.

During a special session on Tuesday, members of the council said the contentious revised charter should be replaced with another charter that honors the city’s unique history, recognizes its Ibaloy heritage and provides more powers to the local government so it could resolve many of its problems.

Go filed an amendatory bill to introduce corrections to RA 11689. But councilors, like lawyer and former city administrator Peter Fianza, said Baguio could use this opportunity to “change it (the charter) entirely,” instead of merely amending the law.

The first proposal to modernize the charter was drawn up in 2001 by the Free Legal Assistance Group and its president, lawyer Pablito Sanidad. It meant to solve the massive backlog of townsite land sales.

The first Baguio charter bill to pass Congress in 2013 incorporated a land swap arrangement that would end the city’s boundary dispute with the neighboring Benguet town of Tuba. It was vetoed by then President Benigno Aquino III.

But the boundary agreement is being revived by the city and Tuba, city legal officer Althea Rosario Alberto told the council.

Councilor Jose Molintas, an Ibaloy human rights lawyer, said the modern Baguio charter should push for the people’s agenda “and not the agenda of other groups being favored by the revised city charter.”

‘Fresh start’

He said a newly written modern charter “will give us a fresh start to decide our priorities for future progress and development [and] a chance to reverse the effects of urban decay.”

Pointing out that the 1909 charter was enacted without consulting or seeking the approval of Baguio’s first settlers, a completely rewritten charter could grant its dominant Ibaloy, Kankanaey and Kalanguya communities the power to review “all ordinances that affect [their indigenous and ancestral land] rights,” Molintas said.

A reworked charter may also remove a section of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, or Ipra, of 1997 (RA 8371) which exempts Baguio and its townsite from the law’s coverage, he added.

“Section 78 of Ipra should be repealed, if not modified, to give justice to Baguio indigenous peoples who lost their lands because of national laws,” Molintas said.

Months before RA 11689 lapsed into law on April 11 last year, the majority of the city council urged then President Rodrigo Duterte to veto the new charter for excluding Camp John Hay from the Baguio townsite and its jurisdiction, for not defining Baguio’s territory and for not undergoing a referendum despite serious policy changes.