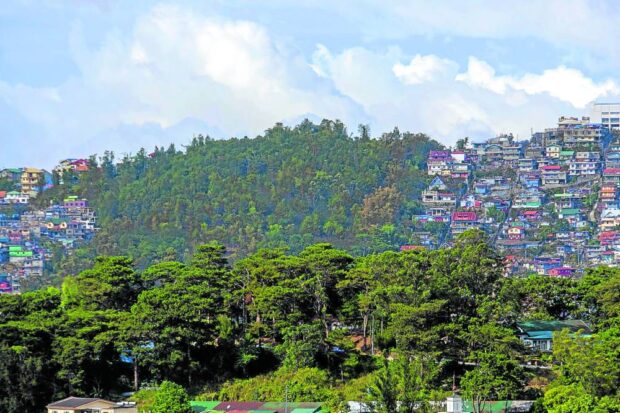

OF PINE AND MEN | Birds, rodents, and native plants continue to thrive in the remaining pockets of “green spaces” around heavily populated sections of Baguio City, like these communities near the pine forest at Buyog watershed, according to local scientists. (File photo by NEIL CLARK ONGCHANGCO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

BAGUIO CITY, Benguet, Philippines — Scientists in this city are studying and recording the animal and plant life that managed to thrive in pockets of “green spaces,” despite the influx of settlers and tourists in an already overcrowded and overdeveloped summer capital.

The initiative undertaken by biologists of the University of the Philippines (UP) Baguio and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) will supplement a draft ordinance being studied by the city council which would designate and preserve the city’s remaining “urban green spaces.”

Councilor Leandro Yangot Jr., who sponsored the measure, said the proposed law would safeguard all vegetated public lands, including parks, tree patches and interior waterways.

Urban green spaces have recently drawn the attention of scientists and policymakers “due to the realization that biodiversity still exists within urban areas,” UP Baguio biology professor Zenaida Baoanan told councilors during their regular session on Monday.

Baoanan, fellow UP Baguio biologist Liezel Magtoto and their research team began assessing the flora (plant life) and fauna (animal life) of Buyog watershed, a unique forest patch that exists between dense settlements in the villages of Quirino Hill and Pinget.

They have since identified 18 bird and nine rodent species there, as well as 31 plant species that require conservation.

The type of animals and plants that dwell in pine forests depend on the elevation, Baoanan said.

Second growth

The Baguio City plateau is 1,400 meters above sea level and is much lower than the dense pine forests in Benguet province like Mt. Pulag, where the cloud rat was rediscovered.

Baoanan pointed out that the local pine woodlands, for which Baguio has been known as the City of Pines, are actually second-growth forests.

In Buyog, the “canopy species,” or dominant tree cover recorded by the research team, are Benguet pine, agoho, and eucalyptus trees, with “understory plant species” or plants found beneath the canopy, such as calliandra and lantana (locally known as “bangbangsit”) which are “invasive species,” she said.

Invasive plants spread wildly in the higher levels of Buyog, Baoanan said.

Among the birds still living in Buyog are the Luzon sunbird, the sulfur-billed nuthatch, the Philippine bush warbler, and the green-backed whistler, which are native there, Baoanan said. Her team found the arctic warbler in higher sections of the watershed at 1,557 meters and the yellow-vented bulbul at 1,434 meters.

Buyog was declared as a 20-hectare watershed by then President Fidel V. Ramos in 1992, but rapid human encroachment reduced this “tropical lower montane forest” to only 8 ha.

‘Human disturbance’

But with the help of active reforestation by the DENR and civic organizations from 2003 to 2022, the narrow patch of the watershed has thickened with trees, Baoanan said.

She said the presence of rats and an abundance of snails, of which 99.5 percent were dead at the time of study, were evidence of “prolonged human disturbance” in their habitat.

The UP team would assess other green spaces in the city as part of the DENR’s urban forest management program, said forester Meagan Kittong-Ayochok, who joined the session.

Many of these green spaces are small, but the healthy ecology found in these pocket green zones “should not be taken for granted,” Baoanan said, noting that the animals and plants there are connected to a fractured Cordillera forest system.

She also advised the city’s lawmakers to put up mechanisms that would manage these green spaces, and restrict or reduce the invasive species that have sprouted there.

The African tulip, a shrub-like tree that secretes chemicals that are fatal to bees, has been growing in different parts of Baguio, Baoanan said. During the discussion, Councilor Jose Molintas said UP’s expertise could also be tapped to audit the biodiversity of lands that are primed for development, “so we can establish how to tax or penalize them for the destruction.”

Councilor Arthur Allad-iw urged the DENR to also evaluate the flora and fauna of private lots. Learning about the ecosystem on their properties may encourage landowners to maintain their idle lands into small forests, to be supported by tax incentives, he said.

The draft urban green spaces ordinance is one of several measures being reviewed by the council to preserve Baguio’s 23-percent forest cover, including a proposed law in 2021 that requires all 128 barangays to identify, manage and, if necessary, fence off communal forests, greenbelts, watersheds and other tree patches found in their territories.

Yangot also sponsored a draft ordinance in 2019 that would designate all pine trees in Baguio as “heritage trees,” to discourage developers from cutting them down.