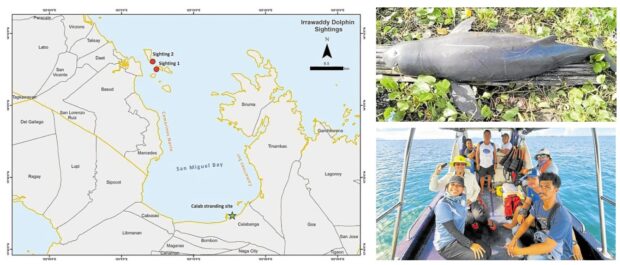

SURVEY MISSION A teamfrom the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology of the University of the Philippines went on a four-day survey mission last week in San Miguel Bay and made two sightings of the rare Irrawaddy dolphins. The mission was prompted by an earlier discovery in August last year of one of the marine mammals off Camarines Sur, where it was caught in a fisherman’s net and eventually died (right upper photo). —MARINE MAMMAL RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION LABORATORY AND UP IESM PHOTOS

Recent sightings of the rare Irrawaddy dolphins in one of the most overfished bays in the Philippines confirmed their existence in the Bicol region—but also indicated risks that can lead to their disappearance from its waters.

This was according to a team of scientists from the University of the Philippines’ Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology (UP IESM) and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), who went on a four-day survey mission from July 6 to July 9 to verify the presence of one of the world’s most critically endangered species in San Miguel Bay.

Led by UP IESM professor and Marine Mammal Research and Conservation Laboratory chief Lemnuel Aragones, the team sighted two of these grey dolphins that are noted for their blunt, rounded heads—one near Apuao Island and another near Canimog Island in Mercedes, Camarines Norte.

Aragones said the team traveled 335 kilometers across San Miguel Bay, covering almost 680 square kilometers of waters off Camarines Norte and Camarines Sur.

Subpopulations

Before this sighting, he said, there were three confirmed subpopulations of the Irrawaddy species in the Philippines, mainly at Malampaya Sound in Palawan province and in the Iloilo-Guimaras-Negros Occidental area.

“These three distinct populations do not interact at all and they are not related to each other,” he said in an Inquirer interview. “This discovery is a validation of the existence of these rare animals outside those areas.”

The Irrawaddy—named after Myanmar’s largest river where they were first documented—often prefer shallow, brackish waters, making the San Miguel Bay an ideal place for them to thrive, Aragones said.

However, the fact that they only saw two dolphins in San Miguel Bay could be taken as a sign of their dwindling population in the area, he said.

For one, it was hard to miss the marine mammals in the bay’s crystal-clear waters since “they would eventually have to break the surface to breathe,” Aragones said.

2022 sighting

He said last week’s four-day mission was prompted by an August 2022 sighting of an Irrawaddy dolphin in Camarines Sur.

The dolphin spotted at the time, which they named Calab, was accidentally entangled in a fisherman’s net in San Miguel Bay off Calabanga and eventually drowned.

It was the first confirmed sighting in Bicol of such a dolphin, which has been declared “critically endangered” both by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

In October last year, both the UP IESM and the BFAR’s Region 5 office interviewed local residents to confirm whether these species have always been there.

Apart from having melon-shaped heads, Irrawaddy dolphins are relatively small compared to the other species (between 2 meters to 2.5 meters long) and are gray-skinned except on their bellies. They also don’t have a rostrum, or a “beak,” but they have a small rounded dorsal fin.

“In one interview, we talked to an old fisherman who said they always saw those dolphins there,” Aragones said. “Back then, the dolphins would sometimes be seen in groups of 20 and were commonly seen close to the shorelines.”

‘Sense of urgency’

Compare this to 2022, where residents said they spotted just one Irrawaddy dolphin.

That they were spotted in one of the most heavily fished areas in the country raises the risk of their eventual disappearance, Aragones warned.

For decades, local fishermen have competed with commercial trawlers that sweep the bottom of the bay for a big catch, leading to overfishing and abuse of the underwater environment.

“So there is a sense of urgency here; we cannot wait for another 10 years to act,” he said.

Aragones said he had appeal ed to the regional BFAR office to impose a moratorium on commercial fishing in San Miguel.

“We need to let the bay take a break,” he said. “The fact that there are now only a handful of these animals (here) and their habitats are very much disturbed means they would soon be in more serious peril.”

RELATED STORY:

Stranded dolphin rescued in Pangasinan