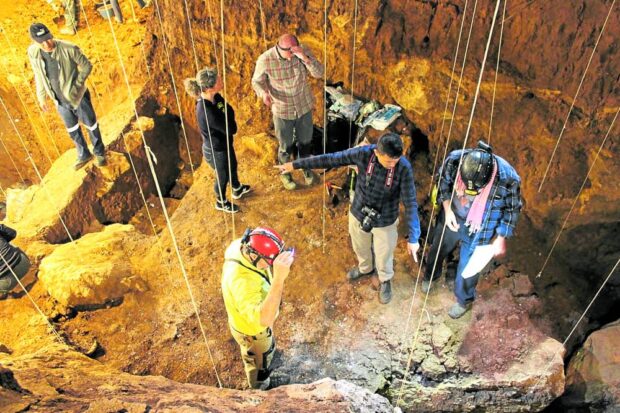

‘OUR ANCESTORS’ Filipino geoarchaeologist Vito Hernandez (second from right, with camera) and fellow researchers at Tam Pa Ling cave, northeastern Laos, where they found bone fragments (below photo) of Homo sapiens. —PHOTOS BY KIRA WESTAWAY/MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AND NATURE COMMUNICATIONS.

Homo sapiens had reached Southeast Asia almost 20,000 years earlier than previously thought.

That research finding challenges current textbook assumptions about early human migration and should provide a wider understanding of the origins of our species.

This was the conclusion made by a team of scientists, including Filipino geoarchaeologist Vito Hernandez, after they unearthed “unmistakable evidence” of fossils and sediments showing that Homo sapiens—the only early species of humans that have survived—arrived in mainland Southeast Asia 77,000 years ago.

Hernandez said these fossils—fragments of leg bones and a skull excavated from Tam Pa Ling cave in northeast Laos—were almost 20,000 years older than previously unearthed fossils in other sites in this region.

Migrant population

By measuring the age of the sediments surrounding the fossils and estimating when these were last exposed to light, the team of mostly French and Laotian scientists, led by anthropologists Sarah Freidline and Fabrice Demeter, estimated the fossils to be between 68,000 and 86,000 years old.

Their study was published in the June issue of the journal “Nature Communications.”

Hernandez, a postgraduate research scholar at Flinders University in Australia, came onboard to explain to the team how the sediments were deposited in the cave and to assist them in dating that evidence.

He said most fossils of prehistoric humans were found in islands like those of the Philippines and Indonesia—citing fossils of Homo luzonensis and of Homo floresiensis.

Fossils previously discovered in mainland Southeast Asia, with its humid climate, were often too weathered or severely fragmented, making them difficult to identify, Hernandez said.

Moreover, “because most of the fossils that we have found so far are in islands, the general thinking was that humans followed the coastlines when we dispersed out of Africa,” he told the Inquirer in an interview.

“Now these findings prove that our ancestors also moved through valleys and forests aside from islands and coasts,” Hernandez said.

The study also showed that these early humans were part of a migrant population—coming from as far as Africa, as he noted.

Bone fragments of Homo sapiens.

Deeper questions

Hernandez said questions about their origins are important in understanding why Homo sapiens “became the successful species” of all the classifications of early humans.

“Why are we still here in the world when everyone else has gone extinct? These questions are important to understand, … possibly to ensure that we survive for another millennia,” he said.

Hernandez said the team hopes to find more evidence of other species of early humans, to “see if their genetic line continues in us.”

This means being able to determine what happened to those species—whether they perished, perhaps as a weak link in the human race, or perhaps had interbred with other humans and were eventually dominated by Homo sapiens.

Researchers hope to be able to clarify these deeper questions about human evolution, Hernandez said.

“In that way, we are able to connect ourselves to Africa,” he said. “In a philosophical sense, there shouldn’t be any reason for racial or geographic discrimination.”

“The past already tells us that we’re all connected,” he added. “Maybe we should focus on understanding our human histories.”