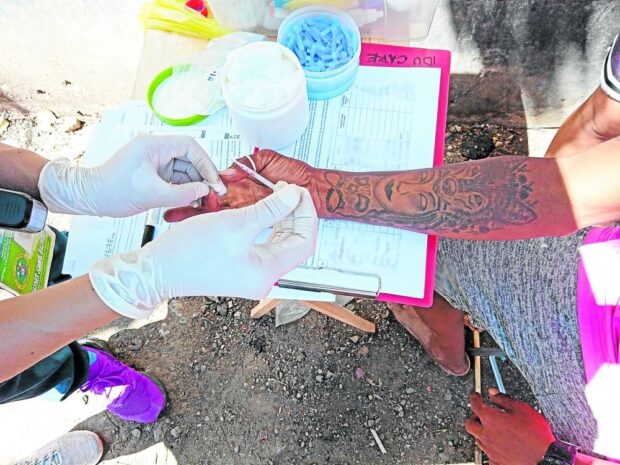

DESERVING HELP | A man avails himself of a blood extraction for HIV and hepatitis testing at the IDUCARE center in Cebu City. (Photo from the Facebook page of IDUCARE)

(First of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines — His record of arrest and detention for drug use during his youth did not discourage Johann “Panki” Nadela, now 49, from advocating a society that understands, not punishes or kills, people like him who need humane care and support the most.

Since 2015 when he cofounded a community drop-in center in Cebu City for people involved in drugs, Nadela has put a face to substance abuse in the country with his experience in drug addiction and its consequences—using his newfound resolve to help seek better options to the drug problem.

“It doesn’t need to be a war,” he said in an interview. “I believe that we can have an environment where persons who use drugs are not arrested, mistreated or killed, but are given the chance to be understood and reintegrated,” he said. “They can receive proper care and treatment and their rights to live normally are restored.”

The former intravenous or injecting drug user (IDU) is the executive director of IDUCARE, a Cebu City organization managed exclusively by former IDUs.

The group still carries its name despite changing terminologies steered by the United Nations and other international organizations to promote a more compassionate language—from IDU to persons who inject drugs (PWIDs), persons who use drugs (PWUDs) and persons involved in drugs.

‘Share our experience’

Nadela started IDUCare with fellow peer educators and site implementation officers who worked under projects funded by The Global Fund to fight tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS, focusing on awareness, care and support especially for persons living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

“We slowly grew and began to be invited everywhere to share our experience and to learn at the same time,” Nadela said.

Apart from counseling, the center has a physician who provides HIV antiretroviral therapies and hepatitis C treatments and a medical technologist who administers tests for HIV and Hepatitis B and C.

Nadela was interviewed on the sidelines of the 27th Harm Reduction International Conference held in Melbourne in April.

He has also been invited to other forums abroad where he learned about other countries’ drug policies and practices on harm reduction—a field that seeks to minimize behavioral risks such as drug use and encourage care for the well-being of persons exhibiting such behavior.

‘We thought it was cool’

Nadela’s life today is a far cry from what he called his “sex, drugs, and rock and roll days,” growing up in Kamagayan village in Cebu where his family owned a store. There he would hang out with friends in high school while getting curious about over-the-counter cough syrups.

“We thought it was cool. It was like Disneyland,” he said, recalling that from syrups, he progressed to marijuana and alcohol.

Into his adulthood, he continued with crystal methamphetamine or “shabu,” and started injecting Nubain, a brand name of nalbuphine, a painkiller.

In 1995, the Department of Health (DOH), nongovernment workers, and academics found a “concentrated epidemic” in Kamagayan involving multiple risks of drug injections and unprotected sexual activity, particularly in a red light district and a hotbed of PWIDs who shared used needles in “shooting galleries” where they bought Nubain.

The DOH continued to report a high incidence of cases of HIV and Hepatitis B and C — the highly infectious, blood-borne diseases caused in part by contaminated injections and unsafe sexual contact.

‘Right to counsel’

Kamagayan has been the focus of many academic and policy studies over the years and has received health and education interventions from government agencies and nongovernmental organizations.

But in 2016, when then President Rodrigo Duterte declared his drug war, PWIDs who were not arrested were moved to other places.

The next year, IDUCare partnered with StreetLaw PH, an organization of human rights lawyers led by its executive director Mary Catherine Alvarez, who saw the gap in legal assistance because of the refusal of some in the legal community to help people involved in drugs.

“Lawyers were willing to assist victims of extrajudicial killings but only in cases of mistaken identity and [those who were] not involved in drugs,” Alvarez said in an interview at a conference on drug policy and public health by the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), held last month in Antipolo City.

“It was understandable at that time because it was scary. The mentality is that we can be tagged as coddlers,” she said. “But I don’t think that was right. There’s stigma and moral judgment on persons who admit to using drugs, that people think they don’t deserve help.”

She added: “It is not an obstacle to legal assistance. A person involved in drugs has a right to counsel. ”

‘We must not judge them’

Alvarez said StreetLaw PH is pushing for a humane drug policy and said the group’s support for IDUCare entails working for access to justice for PWIDs, persons living with HIV and persons deprived of liberty.

She said these groups have intersecting concerns: “We have a community of PWUDs living with HIV.”

IDUCare has also gained the support of Cebu City Health Officer Daisy Villa, who said it was high time for someone like Nadela to help reorient the conversation about drug use.

“We recognize [Nadela’s] efforts and we are by his side to help in any way,” she said in an interview during the UNODC conference. “I agree with him that drug use is a health problem that must be addressed with understanding. There are many reasons why people do drugs. We must not judge them.”

As StreetLaw provided paralegal training to staff and volunteers of IDUCare, the group learned about their difficulties in asserting their rights under the law, Alvarez said.

StreetLaw has also conducted seminars to familiarize participants with the HIV law and is coordinating with the DOH to provide outreach workers with identification cards as safeguards from threats and harassment.

Nadela is also a board member of StreetLaw. “It is important for us that the community we work with is represented,” Alvarez said.

She praised Nadela’s advocacy, saying that IDUCare is so far “the only organized community of PWUDs in the Philippines that is part of the healthcare service providers.”

Barangays cleared

Meanwhile, the Philippine National Police reported that more barangays in the country have been cleared of illegal drugs.

From July 1, 2016, to May 31, 2023, a total of 27,248 barangays, or 76.67 percent of the previously identified 35,356 drug-affected barangays, have been cleared of drugs, the PNP said in a statement on Saturday.

The figure was 1,004 barangays more than the 26,244 drug-cleared barangays reported the previous month.

“While acknowledging the remarkable progress made, we are also aware of the remaining challenges. Currently, 8,288 barangays continue to grapple with drug-related issues,” PNP chief Gen. Benjamin Acorda said in part.

In line with Monday’s celebration of International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, Interior Secretary Benhur Abalos called for the public’s support in the campaign against drugs.

“On World Drug Day, let’s all be Bida champions,” he said on Saturday, referring to Buhay Ingatan Droga’y Ayawan, the Marcos administration’s anti-drug campaign.