Metro Manila residents are now at risk of inhaling microplastics, or tiny plastic fragments in the environment, according to a new study by Filipino scientists who warn of the insidiousness of this new “major pollutant of our generation.”

This was the first time researchers established the presence of microplastics in the ambient air in the Philippines, one of the world’s largest plastic polluters, environmental scientists Rodolfo Romarate and Hernando Bacosa of the Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology said.

“This is really a new realm for us unlike heavy metals in the atmosphere which are heavily studied,” Bacosa said in an interview with the Inquirer.

“This is a major pollutant of our generation and yet there is a dearth of studies and there is a need to further establish [associated risks],” he added.

Published in the Environmental Science and Pollution Research Journal and funded by the Department of Science and Technology, the study tested air samples from 17 local governments in the National Capital Region from Dec. 16 to 31, 2021, or at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Romarate said the team positioned their samples 1.5 meters from the ground “to simulate the average human height.”

They then filtered the air samples and sorted any debris found there.

Landlocked cities

Among other findings, the scientists confirmed the presence of microplastics in all 17 local governments, with the highest concentrations in Mandaluyong and Muntinlupa cities (19).

The lowest concentration of microplastics was found in Malabon (1), followed by Quezon City (2), Pasig (3), Parañaque and Las Piñas (both 5).

For now, it’s unclear why these cities recorded such concentrations, Bacosa said.

But he theorized that wind currents from shoreline cities were blowing the fragments inward, which is why landlocked cities like Mandaluyong were receiving the brunt of it.

Asked to explain the phenomenon in simple terms, Romarate said that if a human being were to inhale three balikbayan boxes’ worth of air in one day, they are likely to breathe in at least one particle of microplastic.

This also means they could inhale up to 88 such particles in a year.

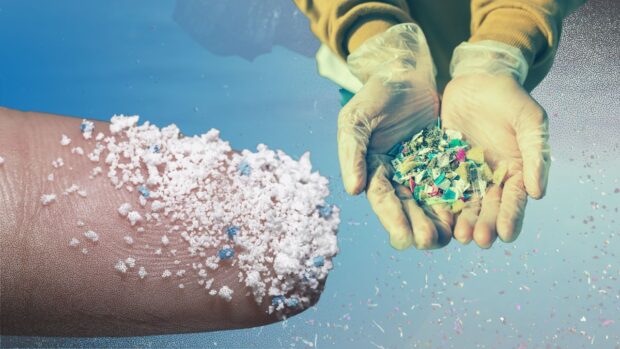

According to the United States National Ocean Service, microplastics are plastic debris less than five millimeters in length, or “about the size of a sesame seed,” and “come from a variety of sources, including from larger plastic debris that degrades into smaller and smaller pieces.”

These include microbeads, or very tiny pieces of manufactured polyethylene plastic that are added as exfoliants to health and beauty products, such as some cleansers and toothpastes.

“These tiny particles easily pass through water filtration systems and end up in the ocean and Great Lakes, posing a potential threat to aquatic life,” the agency said.

But the ocean service acknowledged that as an emerging field of study, “not a lot is known about microplastics and their impacts yet.”

Bacosa, however, cited the findings of earlier studies suggesting potential dangers posed by microplastics on human health, such as those showing they could cause stress to internal organs and enter the bloodstream.

Studies of microplastics in marine life, on the other hand, have also shown that microplastics could cause tissue damage and oxidative stress in fish, he noted.

Bacteria, virus carriers

When suspended, microplastics are also potential carriers of bacteria and viruses, Bacosa added.

Most of the microplastics collected by the researchers for the Metro Manila study were fibrous microplastics, or lint degraded into even smaller sizes, which had likely lofted into the air, Romarate explained.

Both Romarate and Bacosa made it clear, however, that the “fate and the health effects of these [microplastics] would remain uncertain.”

“There are still many aspects to be considered, like the health implications of microplastics in the air or what causes them to be concentrated in certain cities,” Bacosa said.

For now, according to Romarate, their team has forwarded policy recommendations to the national government on how to address what could be a ticking time bomb, including radical changes in the country’s plastic waste management.

“We see these data as something that should make us think about our consumption of plastics but also how we address it as a function of policy,” Bacosa said, adding: “At the end of the day, it is a complex problem.” INQ

RELATED STORY:

Scientists find microplastics in blood for first time