SOUTHAMPTON, United Kingdom — Nowhere suffered as much from the sinking of the Titanic as Southampton and a century after the disaster the city wants to tell the forgotten story of its 549 residents who died.

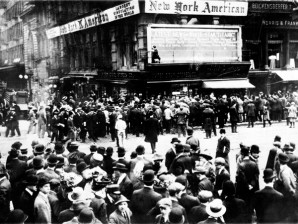

In this April 1912 file photo, crowds gather around the bulletin board of the New York American newspaper in New York, where the names of people rescued from the sinking Titanic are displayed. AP

A job aboard the mighty liner was a dream come true for the men of this port on England’s south coast in 1912, offering three square meals a day and lodgings for the night at a time of severe hardship.

Three-quarters of Titanic’s crew came from the city, many toiling as stokers in the ship’s engine rooms or as stewards tending to the needs of passengers.

When Titanic set off from Southampton docks on her fateful maiden voyage to New York on April 10, 1912, the people of the city cheered it off full of pride.

The contrast could not have been greater five days later when the liner hit an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic, plunging Southampton into mourning and leaving many of the victims’ families in poverty.

“Southampton’s Titanic story is very special because most of the crew came from Southampton and that story hasn’t really been told anywhere else before,” said Maria Newbery, curator of SeaCity, a new maritime museum that focuses on the liner’s crew.

The first news of the sinking was posted in the window of a local newspaper just hours after the disaster, but no one believed it at first.

When the awful truth began to dawn, “a great hush descended,” Charles Morgan, who was nine at the time, recalls in the city’s archives.

“I don’t think that there was hardly a single street in Southampton that hadn’t lost someone on that ship.”

Photographs at the time show anxious relatives gathering around the names of the dead posted outside the offices of the Titanic’s owners, the White Star Line, where a small black plaque on the now-shabby building marks the spot.

Of 724 members of Titanic’s crew with an address in Southampton, just 175 survived, according to figures given by the museum.

One survivor was Alexander Littlejohn, a first-class steward, who was ordered to row one of the lifeboats which were mostly filled with women and children.

His grandson Philip, who gives lectures about the disaster, told Agence France-Presse:

“He was just 40 but the shock of it turned his hair white within months.

In this April 10, 1912 file photo, the Luxury liner Titanic departs Southampton, England, for her maiden Atlantic Ocean voyage to New York. An expedition team using sonar imaging and robots has created what is believed to be the first comprehensive map of the entire Titanic wreck site on the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean. The luxury passenger liner sank about 375 miles south of Newfoundland, Canada, after striking an iceberg on its maiden voyage from England to New York on April 15, 1912, killing more than 1,500 people. (AP Photo, File)

“He never talked about the sinking, which I find is absolutely typical of Titanic survivors. He had mouths to feed so he went on to work on 30 voyages on Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic.”

One of those less fortunate, Sidney Sedunary, a steward, had been carrying a pocket watch which stopped at 1:50 a.m. about half an hour before the Titanic sank.

A few days later, his body was hauled from the water by a rescue ship and the watch, which now takes pride of place in the new museum, was found in his pocket.

The extent of the disaster is poignantly illustrated by a floor map in SeaCity, plastered with red spots to indicate the houses where a crew member was lost. The dots come thick and fast in the working-class areas near the docks.

“Lots of people working as stokers and in the boiler rooms were from Southampton and in the days before social security, if you lost the main breadwinner in the family, you were in trouble,” curator Newbery explained.

The city pulled together to raise money for the bereaved families and in the months after the disaster, every concert and church fete was turned into a Titanic fundraiser.

As the centenary of the disaster approaches, Southampton is acting as a magnet for the descendants of those who perished.

Jane Goodwin, 38, had a special reason to visit the city – her grandmother Cecilia’s first husband Frederick James Banfield sailed on Titanic to join his brother in Michigan where they were planning to work in mining.

“I have seen copies of the letters that he sent her from the Titanic, which are so sad. He was obviously very much in love with her,” the shop worker from Salcombe in southwest England told AFP.

“He was doing so well at such a young age, only 28 years old, and he was going on this magnificent ship for a new life abroad,” said Jane’s husband Richard.

“He had been on the Olympic and in his letter he was comparing the Titanic to these other great ships and he was saying she would have to be there to appreciate how big this ship really was.”