At UN rights body, a ‘landmark victory’ for PH ‘comfort women’

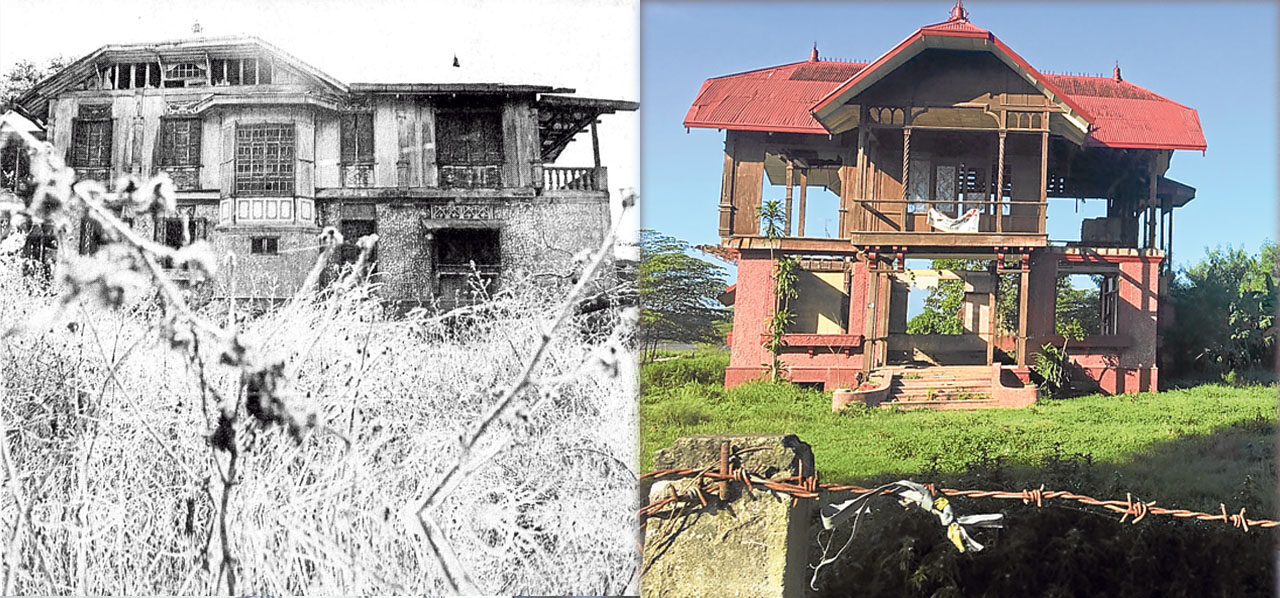

MEMORIAL TO HORRORS The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (Cedaw) is recommending the preservation of the Ilusorio Mansion (1997 photo on left), also called Bahay na Pula (2019 photo, right), in San Ildefonso, Bulacan province, as a memorial to the horrors experienced by young girls, their mothers, aunts and even their grandmothers, who were forced into sexual slavery in this house by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. The UN body says the Philippines violated their rights by failing to provide them with reparation, social support and recognition for their ordeal. —JOANBONDOC/TONETTE T. OREJAS

The women’s group Kaisa-Ka on Thursday hailed as a “landmark victory” the decision by the United Nations’ women’s rights committee to uphold the dignity and welfare of Filipino women victims of military sexual violence during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in World War II.

The victims’ supporters, led by their legal representives, now hope that the Marcos administration will heed the committee’s call for reparations and other acts of recognition to be accorded the women, including telling their story in history classes and preserving the house where they were raped and tortured.

Deciding on a case brought before it in 2019 by the Malaya Lolas, a group of Filipino wartime “comfort women,” the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (Cedaw) said that the Philippines “violated the rights of victims of sexual slavery perpetrated by the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second World War by failing to provide reparation, social support and recognition commensurate with the harm suffered.”

The committee is a body of experts that monitors implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, an international treaty to which the country is a party.

‘Collateral damage’

Article continues after this advertisement“We demand justice for Lolas—for genuine public apology, rehabilitation, restitution and damages from Japan and the Philippines, for our government to take on this demand on behalf of all Lolas,” lawyer Virginia Lacsa Suarez, Kaisa-Ka chair, said in a statement on Thursday.The decision was seen as a fitting tribute to mark International Women’s Day.

Article continues after this advertisementAt present, only 20 of the 24 complainants in the UN case are still alive from the original 96 members of the Malaya Lolas, according to Suarez.

She said women and children suffer the most during wars and militarization as “their bodies are used to refuel the soldiers during their rest and recreation or as shields, and often considered as mere collateral damage.”

In a statement, Cedaw said it requested the Philippines to “provide the victims full reparation, including material compensation and an official apology for the continuing discrimination.”Breaking their silence

“We hope that the Committee’s Decision serves to restore human dignity for all of the victims, both deceased and living,” Cedaw committee member Marion Bethel said.

“This case demonstrates that minimizing or ignoring sexual violence against women and girls in war and conflict situations is, indeed, another egregious form of violation of women’s rights,” Bethel said.The case was filed by Center for International Law in the Philippines (CenterLaw), with Romel Regalado Bagares as consulting lawyer, and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights on behalf of the Malaya Lolas.

The aging and ailing women broke their silence in 1996, 52 years after they were forced to serve as comfort women for Japanese soldiers at Barangay Mapaniqui in Candaba town in Pampanga for several weeks since the Nov. 23, 1944, attack on the village that was suspected to be a lair of the anti-Japanese army Hukbalahap.

They were taken to a mansion-turned-garrison called “Bahay na Pula” in nearby Barangay Anyatam in San Ildefonso town in Bulacan province. Girls were raped in the same room together with their mothers, aunts and grandmothers. The youngest was 9 years old, according to interviews with the victims.After first of them, Maria Rosa Luna Henson of Angeles City, disclosed her wartime ordeal, the women asked the Department of Justice in 1998 to help them file a claim against the Japanese government.

Gov’t argument

They also asked the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Office of the Solicitor General to intercede with the Japanese government on their behalf but both offices dismissed the request.According to Cedaw, the government argued that the “individual claims (of the comfort women) for reparations had been waived under the Treaty of Peace with Japan and that, in any case, the authors had already received compensation from the Asian Women’s Fund.”

In a statement in January 2016, then Presidential Communications Operations Secretary Herminio Coloma Jr. said Japan’s war reparations had long been resolved.

But he said that the government would not block any “private claims” for war crimes.

Not covered

The treaty and the $550 million worth of goods and services for reparations—the highest amount received by any country from Japan after the war—were intended for economic recovery, plus S20 million in compensation for war veterans, their widows and orphans, said Miguel Reyes of the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines. Citing well-documented reports, he said dictator Ferdinand Marcos had gotten kickbacks from reparations contracts and deposited them in his Swiss bank accounts.This treaty, nevertheless, did not cover the comfort women, who only came out decades later, Reyes said.

In 2004, CenterLaw petitioned the Supreme Court to compel the concerned government offices to back the claims of the Malaya Lolas.

In its final ruling in 2014, the high court said that the executive branch had the exclusive prerogative to determine whether to espouse the claims against Japan and that the Philippines had no international obligation to support those claims.On Nov. 23, 2021, Isabelita Vinuya, then president of the Malaya Lolas, died of pneumonia. Suarez then noted that it was on that same day in 1944 when the Geki Group of Japan’s 14th District Army under General Tomoyuki Yamashita attacked Mapaniqui.

10 songs

Survivors said that the men and boys were massacred, some of them castrated, and their bodies thrown into a pit.The remaining Malaya Lolas are now bedridden and sickened by old age, hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, asthma, arthritis and other ailments.

The Malaya Lolas had documented their ordeal in 10 songs they wrote in the style of “pangangaluluwa,” or hymns for the departed souls.

Several lines from the main song went: “At nang magsawa na, kami’y pinawalan/ Halos ang hininga’y ibig nang pumanaw/Sa laki ng hirap na pinagdaanan/Sira na ang isip pati na katawan” (And when they were done, we were released/Nearly out of breath/After the ordeal we had gone through/Mind and body both ravaged.)

Before her death, Vinuya had said: “It is not only compensation that we are after. We should keep fighting so that in future wars, the sexual abuse of women is not used again to defeat our people.”

Bagares said the Philippines needed to act swiftly and “not any more begrudge the women this entitlement.”

“Given the extreme violence suffered by the comfort women, the government should really move fast to provide them the reparations, rehabilitation and support they deserve,” Bagares said.Memorial, curriculum

Both Bagares and Suarez hope that the Philippine government would recognize its responsibility under its international obligations.

Among others, the Cedaw decision compels the Philippines to provide reparations and to set up a nationwide fund for all victims of wartime atrocities.

It recommended the establishment of a state fund to provide compensation for the victims, and to create a memorial to preserve the site of Bahay na Pula.The government should also cite the wartime sex slaves in school curriculum “as remembrance is critical to a sensitive understanding of the history of human rights violations endured by these women, to emphasize the importance of advancing human rights, and to avoid recurrence.”

Bagares suggested that President Marcos issue an executive order providing reparations to the women, or to order Congress to file a bill similar to how former President Benigno Aquino III passed the martial law memorial law. —WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH INQ