Jeepney phaseout: It’s more than just new vehicles

INQUIRER COMPOSITE IMAGE: DANIELLA MARIE AGACER FROM AFP AND INQUIRER.NET FILE PHOTOS

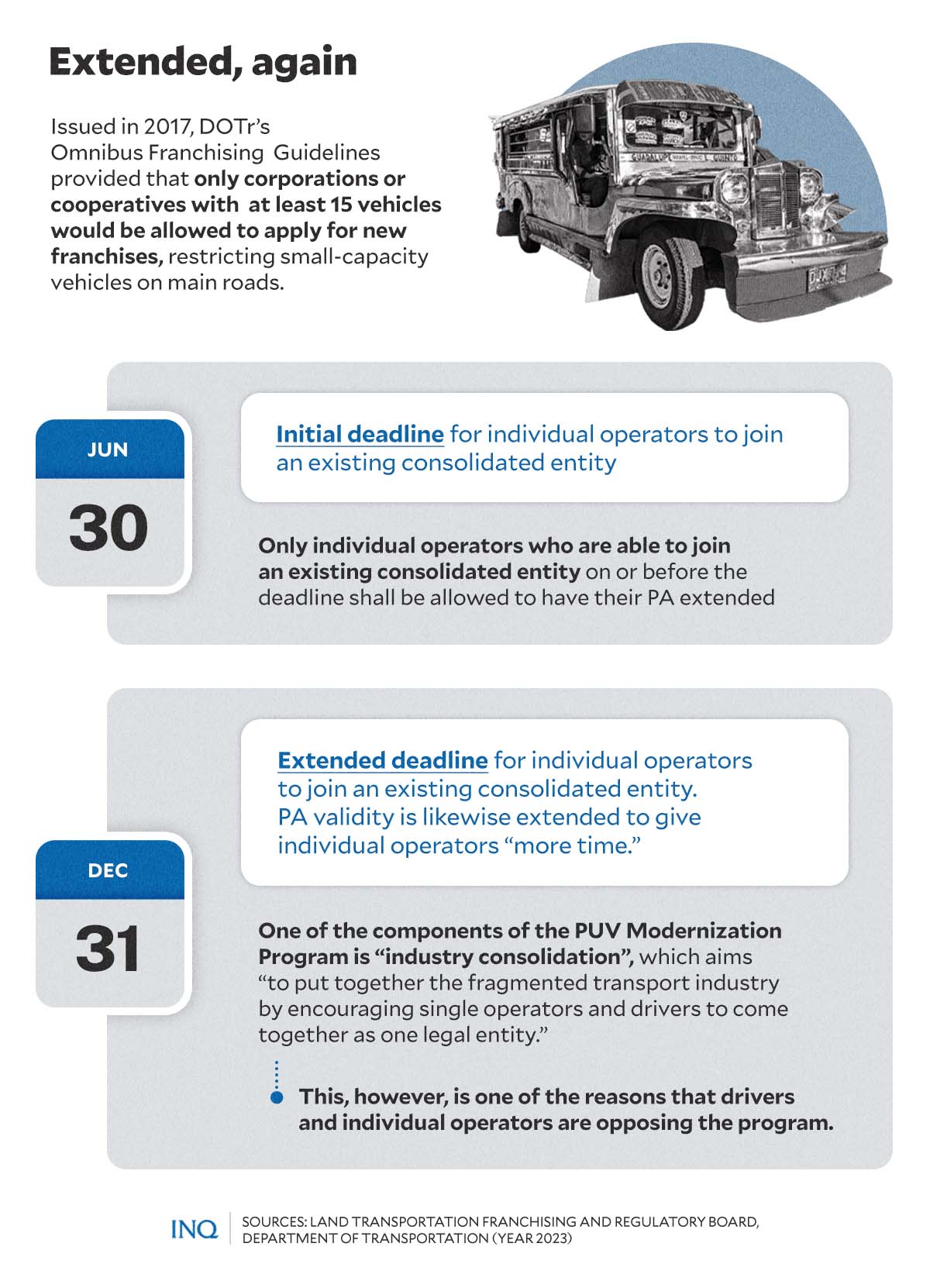

MANILA, Philippines—The validity of provisional authorities (PAs), which allows individual operators to ply traditional jeepneys, has been extended again but transport group Manibela vowed to proceed with its week-long strike from March 6 to 12.

Mar Valbuena, national president of Manibela, told INQUIRER.net that the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) did not heed any of the group’s calls.

“We will proceed with the strike. What the LTFRB released is just an extension of our agony since it did not contain any of the provisions we have been asking them to include,” he said.

READ: Week-long transport strike on March 6 will continue, says Manibela

It was on Feb. 27 when transport groups, like Manibela and Piston, decided to stage a week-long strike to protest the “phaseout” of traditional jeepneys and convince the LTFRB to shelve the implementation of the Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program (PUVMP).

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

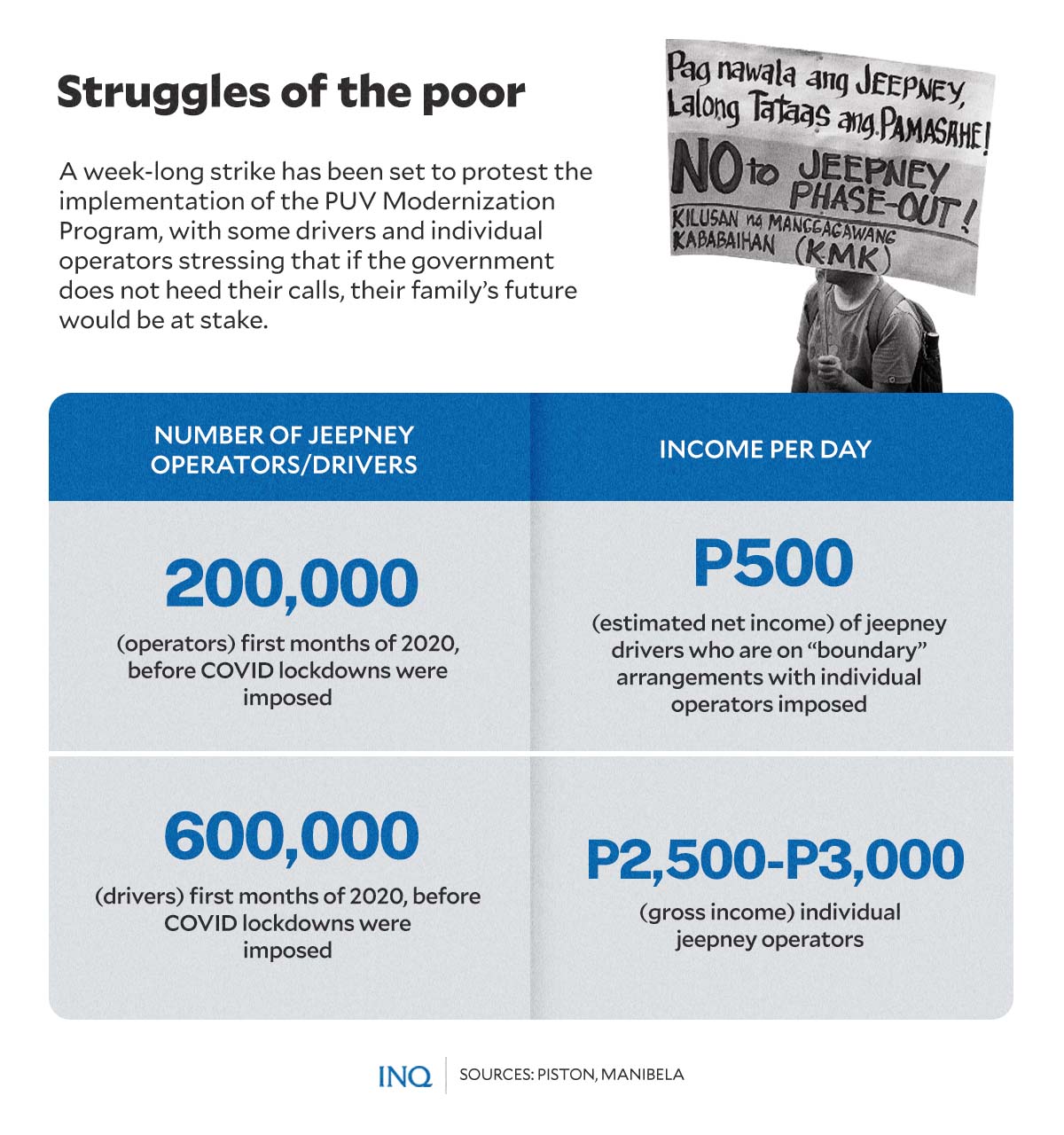

As stressed by Piston national president Mody Floranda, “drivers and small operators are ready to protect their livelihood because the lives of their families are at stake, especially at a time of intense economic crisis.”

But on March 2, the LTFRB said it decided to extend the validity of the PAs, or franchises, of traditional jeepneys from June 30 to Dec. 31 to give individual operators “more time” to consolidate into corporations or cooperatives.

This, as based on the Department of Transportation’s (DOTr) Omnibus Franchising Guidelines, only individual operators, who are able to join an existing consolidated entity on or before the deadline, shall be allowed to have their PA extended.

READ: Jeepney franchises extended

The LTFRB, however, stressed that the decision to extend the validity of PAs was not brought by pressure from the planned strike, which Manibela said was expected to be backed by close to 100,000 drivers and operators all over the Philippines.

Based on data from Manibela, out of the 100,000 drivers and operators, 40,000 are in Metro Manila. So as a result, millions of commuters will be affected, Elvira Medina, chairperson of the National Center for Commuters Safety and Protection, said.

She told CNN Philippines that 8 million commuters in Metro Manila alone will directly feel the impact of the week-long strike. Local executives in the region already directed the deployment of all available vehicles to provide commuters with free rides.

‘Modernization’ hits hard

Looking back, it was in 2017 when the government launched its biggest non-infrastructure program through DOTr Department Order No. 2017-011, or the PUVMP.

This, as the DOTr said it shall reduce reliance on private vehicle use and move toward environmentally-sound mobility solutions, and shall develop and promote high quality public transportation systems.

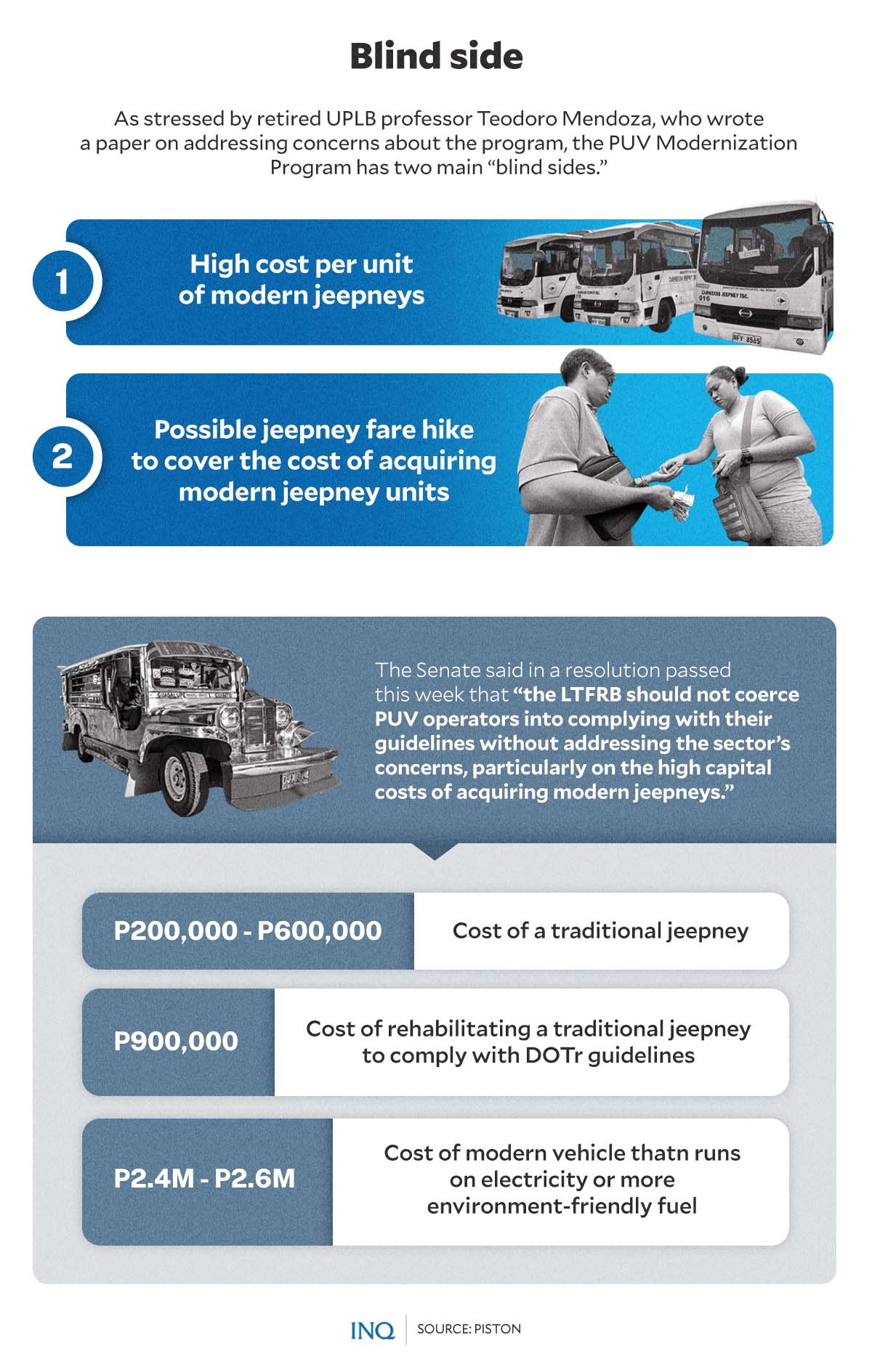

As stressed by retired University of the Philippines Los Baños professor Teodoro Mendoza, who wrote a paper on addressing the “blind sides” of the PUVMP, the program seeks to replace old PUVs, including jeepneys, with modern ones.

Mendoza’s “Addressing the ‘blind side’ of the government’s jeepney ‘modernization’ program” was published by the UP Center for Integrative and Development Studies’ Program for Alternative Development.

“Modern PUVs,” he said are more environment-friendly and fuel-efficient to provide Filipinos with safer, comfortable, and reliable public transportation, while also mitigating the “hazards” of “inefficient and smoke-belching PUVs.

RELATED STORY: Obstacle to jeepney modernization

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“However, this ‘solution’ to road safety and climate change is seen as a problem by its stakeholders, given the divergent realities in the backdrop of the program and the import-dependent nature of the said ‘modernization’,” he said.

Floranda told INQUIRER.net that drivers are not totally against the PUVMP, stressing that “what we are opposed to is the way the government is implementing the program, where big businesses, especially those overseas, are advantaged.”

Even the Senate expressed concern over the implementation of the program, saying in a resolution passed this week that the LTFRB should first address problems confronting the PUVMP.

“The LTFRB should not coerce PUV operators into complying with their guidelines without addressing the sector’s concerns, particularly on the high capital costs of acquiring modern jeeps,” said the Senate resolution.

Too expensive

As stressed by Mendoza in his 2021 paper on jeepney modernization, the PUVMP has two main “blind sides”—the high cost per unit of modern jeepneys and the possible fare hike to cover the cost.

He said based on data, modern vehicles that operate through electricity or more environment-friendly fuel are “expensive” at P2.4 to P2.6 million each in 2020, which meant an increase in capital outlay for operators of P1.4 million to P1.6 million.

Piston earlier said this was way too expensive compared to a traditional jeepney, which only costs P200,000 to P600,000. As Floranda said, if the government does not want the traditional ones, it should at least let individual operators “rehabilitate” their units.

This way, “modernizing won’t be too expensive,” he said, explaining that in one instance, an individual operator who rehabilitated his jeepney in accordance with the DOTr’s Omnibus Franchising Guidelines, only spent P900,000.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Based on the DOTr guidelines, a modern jeepney should be less than 7 meters in length with door locations allowing boarding and alighting only from the curbside, not from the rear.

It should likewise have a GNSS receiver, free Wi-Fi, CCTV with continuous recording of past 72 hours of operations, automatic fare collection system for PUJs and UV Express within highly urbanized independent cities.

The modern jeepney is “appropriate as feeder services operating in arterial, collector, and local roads, linking neighborhoods and communities to mass transit lines and bus routes, and traversing commercial, industrial, recreational, or residential areas.”

Modern vehicles, like the minibus, meanwhile should either be non-air conditioned, air conditioned, loop, shuttle, and/or express with fare collection that is based on distance and/or zone.

The DOTr stated that a minibus should be single deck with no wooden components and is 7 to 9 meters in length and should have a mini coach with emergency exit, tempered glass windows.

The guidelines provided that for urban routes, the minibus should be low entry for quick boarding and alighting, and with space for at least one passenger with wheelchair and foldable or retractable wheelchair ramp at the curbside.

A minibus operates along major arterial roads, highways, expressways and identified collector roads, and are “appropriate for corridors where demand may be sufficient for operation or larger-sized buses.”

Almost impossible

As Floranda stressed, “who would not want a more efficient and comfortable vehicle?”

The problem, however, is that acquiring a new unit, which costs P2.4 to P2.6 million each, is almost impossible for drivers and small operators who only rely on everyday operation to recoup expenses.

Floranda said a driver who is on a “boundary” agreement with an individual operator only brings home an average of P500 from over 12 hours of plying highly congested roads.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

He explained that the P500 is from the P2,500 to P3,000 daily gross income of the small operator. Expenses for fuel and maintenance will also be deducted from the gross income.

“This is the reason that we are calling for rehabilitation as a way to ‘modernize’ instead,” Floranda said, stressing that rehabilitation will also strengthen the local industry, which in turn is expected to provide more jobs.

Dindo Rosales, a representative of the Alyansa Kontra PUV Phaseout, said “we are against this deadly modernization program that promotes loans,” pointing out that drivers don’t want themselves to be buried in debt.

RELATED STORY: Jeepney operators strike back

As explained by Mendoza, to address the high cost of modern PUVs, the Development Bank of the Philippines and the Land Bank of the Philippines had each designed a loan facility for the program.

‘No to consolidation’

One more reason for the opposition to the PUVMP is “Industry Consolidation,” which aims to “put together the fragmented transport industry by encouraging single operators and drivers to come together as one legal entity.”

Based on the DOTr’s Omnibus Franchising Guidelines, only corporations or cooperatives with at least 15 vehicles would be allowed to apply for new franchises, restricting small-capacity vehicles on main roads.

However, some small operators are protesting, stressing their concern that they do not have enough resources to complete the requirement of 15 units.

Ricardo Rebaño, president of the Federation of Jeepney Operators and Drivers Association of the Philippines, pointed out that operators would need to pay a monthly amortization of P475,000 to operate 15 modern vehicles.

As stressed by Floranda, mandating operators to consolidate their individual franchises under a cooperative or corporation is “wrong, deceitful, and coercive” as it deprives operators of their rights and privileges as individual franchise holders.

He said “only big corporations with single consolidated franchises have the financial capacity to purchase and fully comply with the current PUVMP schemes.”

It was explained by Floranda that once you consolidate your franchise under a cooperative or corporation, you surrender your right to have an individual franchise: “Once you fail to shoulder the weight of expensive modernization, you have nothing to go back to.”

“What happens to the consolidated franchise of your cooperative? It will be bid out by the LTFRB to large corporations who have the capacity to pay for imported minibuses promoted by the government,” he said.

With the new deadline set on Dec. 31, individual operators have 10 months to consolidate.

As Transportation Secretary Jaime Bautista said, “the phaseout will happen in areas where the modernization program is almost already implemented in full.”

“But in areas where we think that we know it’s hard to get new equipment right away, we will give operators a chance to join cooperatives to consolidate so that they get the help they need to get new equipment,” he said.

Bautista assured operators that “no phaseouts will happen yet in areas where new units still cannot realistically operate.”

Some 61 percent, or 96,380 of the 158,000 target jeepneys nationwide, have complied with the consolidation requirements of the public utility vehicle (PUV) modernization program, the LTFRB said.

Joel Bolano, LTFRB technical division chief, said across the Philippines, there are already more than 5,300 units of modernized jeepneys operating.

Gov’t will help

“We are willing to bend backward, suggesting to the board of LTFRB to relax the requirements to enable drivers to [adapt] to the program,” Bautista said.

He said “we even offered to dialogue with drivers associations displeased with the PUVMP to explore how they can be accommodated into the program.”

Bautista, however, did not specify which requirements he was referring to, but the LTFRB told INQUIRER.net that this is the same order that moved the LTFRB to extend the deadline until Dec. 31.

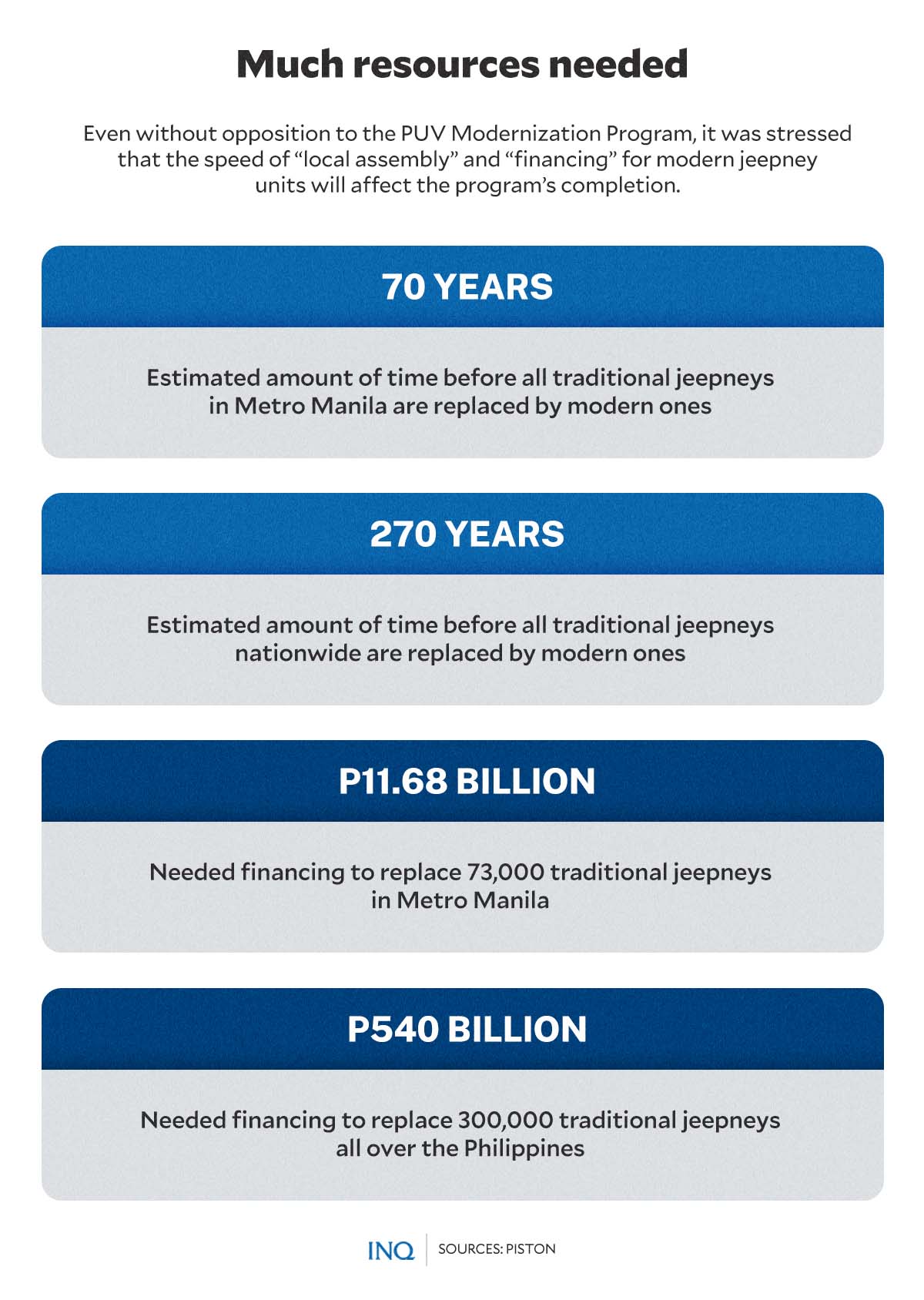

Mendoza explained that there are two numeric aspects of the PUVMP that must be considered to complete the program, assuming that there is no more opposition from the drivers and operators.

“These are the speed of local assembly of the modern jeepneys and financing for the jeepney units,” he said.

READ: As strike looms, gov’t moves jeepney franchise deadline

“With the very slow rate of local assembly of modern jeepneys (at only 1,000 units per year), it will take 70 years before all the traditional jeepneys in Metro Manila will be replaced with modern jeepneys,” he said.

Then for all traditional jeepneys in the Philippines to be replaced, it will take 270 years, even if there is no more opposition from drivers and operators.

A large amount is also needed for the program, he said.

For Metro Manila alone, about P11.68 billion is needed for the 73,000 traditional jeepneys to be replaced. To replace 300,000 traditional jeepneys nationwide, financing will amount from P540 billion to P750 billion.

“Given this, will government banks have sufficient money to fund this enormous project of the government and will these banks provide loans to new cooperatives that are yet to have a track record in managing huge amounts of loans? The expensive modern jeepney seems to present an insurmountable problem rather than a solution,” he said.

“Achieving the goals of jeepney modernization requires a considerable amount of resources (e.g., funding and infrastructure) and suitable management (e.g., cooperative-led or private-led fleet management),” he said.