Fishers in Bohol town want whale sharks out

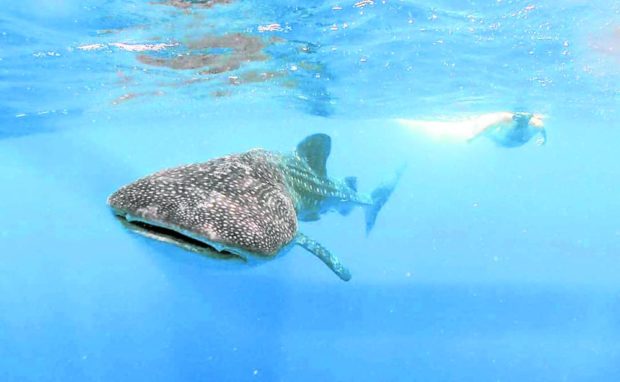

SWIMMING WITH ‘BUTANDING’ | While whale sharks have become tourist attractions in Lila, Bohol, where visitors can swim with them, as shown in this 2019 photo, such is not the case in the neighboring town of Loay where fishermen consider the marine creatures, locally called “butanding,” as a threat to their livelihood. (Photo by JESSE ACEBES / Contributor)

TAGBILARAN CITY, Bohol, Philippines — Whale sharks may be welcome in the waters of most coastal towns due to their potential to attract tourists, but not in Loay, Bohol, where fishermen consider them a threat.

Fisherfolk in Alegria Sur in Loay said they would go to the provincial board to express their sentiments and to ask officials to address the matter.

“They (whale sharks) eat our fish, our source of livelihood. It scares us because we might no longer have enough for ourselves,” Calino Permoso, 44, president of Alegria Sur Fishermen Association, said in Cebuano.

Some fishermen in the Loay villages of Palo, Alegria, and Sagnap shared Permoso’s sentiments.

They said whale-shark watching in the neighboring town of Lila, at least 6 kilometers from Loay, was already enough to encourage tourists to visit Bohol.

Article continues after this advertisement“We don’t want them here,” said fisherman Roque Bagnol, 60.

Article continues after this advertisementLast year, fishermen discovered the presence of three to five whale sharks, at least 12.19-meter (40-feet) long, in the sea off Loay and Alburquerque towns.

In the past four months, Permoso said they observed two unidentified men from Pamilacan Island feeding the whale sharks with “bolinaw” (anchovy) daily.

Reduced catch

According to marine conservationists, feeding the whale sharks lures them to stay in a specific area.

Permoso said they learned that the two men were paid by a local official who planned to develop the area for whale-shark watching.Before the whale sharks arrived, Permoso said they used to catch 30 pails of anchovy daily and sold them for P2,000 to P2,300 per pail, which contains at least 24 kilos worth of anchovies.

The catch became scarce with the whale sharks feeding in their waters, he said.

“We are really affected. We would be lucky if we have at least 5 kilos of catch (daily),” said another fisherman Anthony Silagan, 43.

Whale sharks, the world’s biggest fish species and known here as “tuki-tuki,” or “butanding,” usually feed on a large variety of plankton, the small and microscopic organisms drifting or floating in the sea.

Fishermen avoided the sharks, especially their gaping mouths, while swimming close to the water’s surface.

“We almost met an accident when these whale sharks bumped our pump boat,” Silagan said.

Protected

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are protected marine animals governed by local and international protection laws. They are among species on the lists of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and of the Convention of Migratory Species.

The Bohol Sea is one of the breeding grounds of whale sharks and dolphins that are popular in the seas off the towns of Jagna and Lila as well as on Pamilacan Island in Baclayon town, known as the “highway of the whales.”

But sightings of whale sharks and dolphins declined in the early 1990s due to rampant hunting.

Free the Whale Sharks Coalition-Bohol (FWSCB), composed of multisectoral groups, civil society organizations, and concerned citizens, earlier condemned the feeding of whale sharks, calling it an “ecological trap.”

Whale sharks, according to environmentalists, are highly migratory animals that should not be trained to stay in one place.

“Bohol and we, the Bol-anons, must remain true to and continually pursue our eco-cultural identity and ideals. Let us [allow] the whale sharks to swim freely in Bohol and elsewhere,” FWSCB said.