Robots set sights on new job: Sewing blue jeans

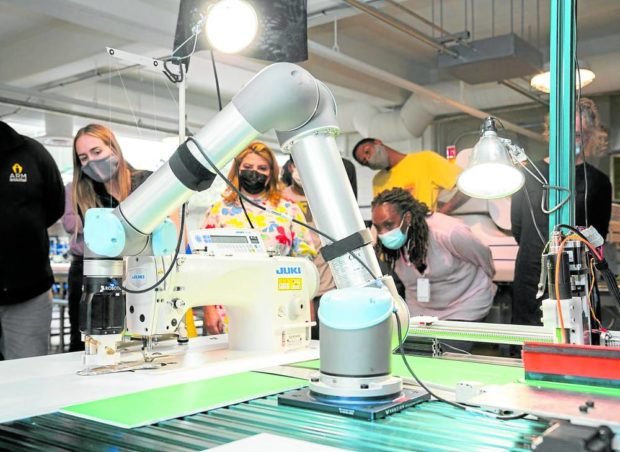

TAILORING TECH | A robotic arm positions pieces of stiffened fabric for a demonstration of automated sewing at the Industrial Sewing and Innovation Center in Detroit, Michigan, United States, on Aug. 19, 2021. (REUTERS)

Will a robot ever make your blue jeans?

There is a quiet effort underway to find out — involving clothing and technology companies, including Germany’s Siemens AG and Levi Strauss & Co.

“Clothing is the last trillion-dollar industry that hasn’t been automated,” said Eugen Solowjow, who heads a project at a Siemens lab in San Francisco that has worked on automating apparel manufacturing since 2018.

The idea of using robots to bring more manufacturing back from overseas gained momentum during the pandemic as snarled supply chains highlighted the risks of relying on distant factories.

Finding a way to cut out handwork in China and Bangladesh would allow more clothing manufacturing to move back to Western consumer markets, including the United States. But that’s a sensitive topic.

Article continues after this advertisementMany apparel makers are hesitant to talk about the quest for automation — since that sparks worries that workers in developing countries will suffer. Jonathan Zornow, who has developed a technique to automate some parts of jeans factories, said he has received online criticism – and one death threat.

Article continues after this advertisementA spokesperson for Levi’s said he could confirm the company participated in the early phases of the project but declined to comment further.

Floppy cloth problem

Sewing poses a particular challenge for automation.

Unlike a car bumper or a plastic bottle, which holds its shape as a robot handles it, cloth is floppy and comes in an endless array of thicknesses and textures. Robots simply don’t have the deft touch possible with human hands. To be sure, robots are improving, but it will take years to fully develop their ability to handle fabric, according to five researchers interviewed by Reuters.

But what if enough of it could be done by machine to at least close some of the cost differential between the United States and low-cost foreign factories? That’s the focus of the research effort now underway.

Work at Siemens grew out of efforts to create software to guide robots that could handle all types of flexible materials, such as thin wire cables, said Solowjow, adding that they soon realized one of the ripest targets was clothing. The global apparel market is estimated to be worth $1.52 trillion, according to independent data platform Statista.

Siemens worked with the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute in Pittsburgh, created in 2017 and funded by the Department of Defense to help old-line manufacturers find ways to use the new technology. They identified a San Francisco startup with a promising approach to the floppy fabric problem.

Rather than teach robots how to handle cloth, the startup, Sewbo Inc., stiffens the fabric with chemicals so it can be handled more like a car bumper during production. Once complete, the finished garment is washed to remove the stiffening agent.

“Pretty much every piece of denim is washed after it’s made anyway, so this fits into the existing production system,” said Zornow, Sewbo’s inventor.

Enlisting robots

This research effort eventually grew to include several clothing companies, including Levi’s and Bluewater Defense LLC, a small US-based maker of military uniforms. They received $1.5 million in grants from the Pittsburgh robotics institute to experiment with the technique.

There are other efforts to automate sewing factories. Software Automation Inc, a startup in Georgia, has developed a machine that can sew T-shirts by pulling the material over a specially equipped table, for instance.

Eric Spackey, CEO of Bluewater Defense, the uniform maker, was part of the research effort with Siemens but is skeptical of the Sewbo approach. “Putting (stiffening) material into the garment-it just adds another process,” which increases costs, said Spackey, though he adds that it could make sense for producers who already wash garments as part of their normal operation, such as jeans makers.

The first step is getting robots into clothing factories.

Sanjeev Bahl, who opened a small jeans factory in downtown Los Angeles two years ago called Saitex, has studied the Sewbo machines and is preparing to install his first experimental machine.

Leading the way through his factory in September, he pointed to workers hunched over old-style machines and said many of these tasks are ripe for the new process.

“If it works,” he said, “I think there’s no reason not to have large-scale (jeans) manufacturing here in the US again.”