Manila Clock Tower Museum: Darkest hours, brighter times

NATIONAL ICON History and art converge within the walls of the Manila Clock Tower Museum. The top floor offers visitors a 360-degree view of the capital city’s busy streets and green parks. There’s a plan to use a vacant space at the museum for a tribute exhibit for architect Antonio Toledo, who designed the clock tower.

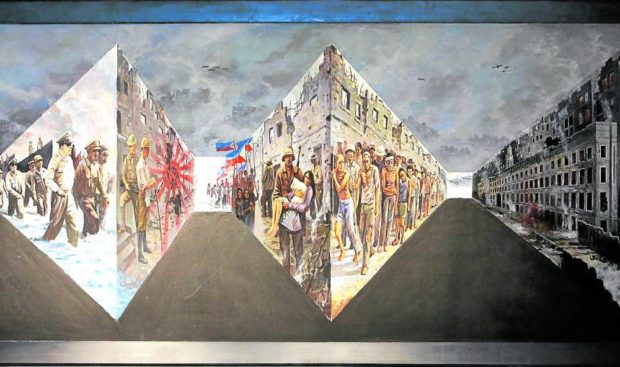

A bombed-out metropolis lay in ruins, buildings toppled and streets scarred with wreckage and debris. And yet, four years earlier, the then bustling national capital declared itself an “Open City,” precisely to avoid such destruction and bloodshed as a brutal foreign invader approached. This is Manila during World War II, but there’s neither noise nor movement now, only stillness amid depictions of chaos.

It’s a place that seems frozen in time, but the seconds are ticking away constantly at the Manila Clock Tower Museum, the newest tourist attraction at the heart of City Hall.

The museum, consisting of six levels, first takes visitors back to the Battle for Manila in 1945, when American and Japanese forces fought street by street for control of the besieged capital. The monthlong fighting, from Feb. 3 to March 3, ended three years of Japanese occupation at a terrible cost with the death of about 100,000 civilians.

On the ground floor, the black-and-white wartime photos depict the various stages of the siege: From residents fleeing and wandering in the streets, structures up in smoke, to soldiers attending to the wounded.

But the narrative extends backwards to also cover events of months before, such as the historic return of Gen. Douglas MacArthur and the US troops in Palo, Leyte, on Oct. 20, 1944. Further flashbacks show prewar Manila also in pictures, aurally enhanced by music and radio broadcast recordings from that era.

For a more tactile experience, suspended in midair are pieces of wooden debris—and a mock-up bomb dropped from a warplane. On the mezzanine, a photo gallery is dedicated to the fallen soldiers of Manila’s Liberation.

Rise to modernity

LIBERATION The capital’s painful wartime past is the main theme of artworks on the ground floor, featuring vignettes before, during and after the Battle of Manila.

But the museum is not all about death and devastation.

As visitors ascend the stairs, the depiction of Manila also moves away from its war-ravaged period. One is greeted by works of Filipino visual artists, like the notable Rene Robles and his protégés Sherwin Paul Gonzales and Nante Carandang. An exhibit titled “Assertionism Epilogue” celebrates the art movement Robles founded.Jose Belmonte, the head of the museum project, defined assertionism as “the power to transform, transcend and create,” a fitting theme capturing the city’s rise from the ashes of war.

Featured on the same floor are award-winning pieces from the Tawid Gallery collection, including “Anino” by Thomas Daquioag, the grand prize winner in the 2000 Art Association of the Philippines National Painting Competition.

An exhibit of Joe Datuin’s metal sculptures and artworks is on the next floor. In 2008, Datuin won an international art contest tied up with the Beijing Olympics. Quaint furniture made by Agi Pagkatipunan also serve as conversation pieces in this section.

The displays on these two levels are for sale, according to Belmonte, with the city government taking a 9-percent to 10-percent commission for every work sold.

“The exhibits are to be replaced every two to three months,” he said in an Inquirer interview. One of the artists to be featured next is Melissa Yeung-Yap, whose works fuse modern idioms with indigenous Filipino elements, he said.

‘Instagrammable’

ART SHOWCASE The Manila Clock Tower Museum features the works of various Filipino artists.

The exhibits are “to be replaced every two to three months,” says Jose Belmonte, museum project head. —PHOTOS BY MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

Another floor offers a photo-op area modeled after the Manila mayor’s office, complete with a stately table, leather chair and a desk stacked with documents. Belmonte said this room was meant to be “Instagrammable.”

In the same area, the visitor is introduced to the past city mayors through the reproductions of their official portraits. The originals can be found at the second floor of City Hall.

Behind the mayor’s room is a small library of Filipiniana books donated to the museum, some courtesy of heritage groups.

The next level serves as a multipurpose hall for art workshops, competitions and artifact restoration. “We can invite artists to teach kids here,” Belmonte said.

Gonzales, one of the founders of the Tareptepism style and an awardee of the 2012 Senate Gold Medal for Academic Excellence, is the museum’s resident artist.

An icon in itself

NATIONAL ICON History and art converge within the walls of the Manila Clock Tower Museum. The top floor offers visitors a 360-degree view of the capital city’s busy streets and green parks. There’s a plan to use a vacant space at the museum for a tribute exhibit for architect Antonio Toledo, who designed the clock tower.

A national icon in itself, the Manila Clock Tower was built in the 1930s, with its most recent renovation done in 2014. The work involved not only sprucing up the structure but also ensuring that the four clocks remained accurate and in sync.

Plans have been drawn up to set up another exhibit, one that pays tribute to the tower’s architect and designer, Antonio Toledo.

Opened to the public on Oct. 25, the museum is open on Tuesdays to Fridays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Admission is free but visitors must make reservations online through the museum’s Facebook page, as only 15 people are allowed per tour.

These restrictions are in line with pandemic protocols and also in consideration of the structure’s age, Belmonte said. INQ

RELATED STORIES

Manila resurrects its iconic clock tower