‘Ghosts that shape who we are’: The PH genome project

In a modest laboratory on the University of the Philippines (UP) campus in Diliman, Quezon City, a small team is hard at work solving one of science’s most complex puzzles: the human genome.

It’s an arduous task that will take years to complete: this sequence of 3 billion chemical letters that is the sum of all genetic material in the body varies from person to person, or perhaps more so, from Filipino to Filipino.

In the Philippines, where ethnicities, languages and religions intersect, deciphering the Filipino genome means determining which groups are close or distant to one another at the genetic level, and those findings can have profound implications in medicine, anthropology, forensics and history.

It is for this purpose that researchers at UP Natural Science Research Institute (NSRI) are untangling the nation’s diverse genetic heritage to establish a local genome databank representing the various regions and ethnicities.

‘Purity’ of native genes

To do that, the researchers need to sample the DNA of 2,870 adults from those groups, but they have to be picky with their subjects. Volunteers, as well as their parents and grandparents on both sides, must be natives of one region or members of an ethnic group; must speak the same language; and must not be biologically related to other subjects.

Article continues after this advertisementThis is a tough entry barrier, and the researchers have discovered it is not easy to locate natives from each region or group even up to the third generation—or just as far back as the 1970s. In some barangays, villagers trace their genealogy to the Japanese or the Chinese; in others, entire communities can be traced to one family.

Article continues after this advertisementBut it’s not exactly the “purity” of native genes they are most after, according to the scientists. Ultimately, they hope to capture the Filipino’s story at a molecular level: from its beginnings to its evolution.“We want to see how the modern Filipino genetic structure is now (and) also capture old genetic signals that could show us what we have lost through time,” said Frederick Delfin, one of the program’s team leaders.

“It’s like finding the ghosts that continue to shape who we are,” he said.

The ambitious program, called the Filipino Genome Research Project (FGRP), is a three-tiered, P173-million project led by the NSRI’s DNA Analysis Laboratory and supported by the Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Health Research and Development.

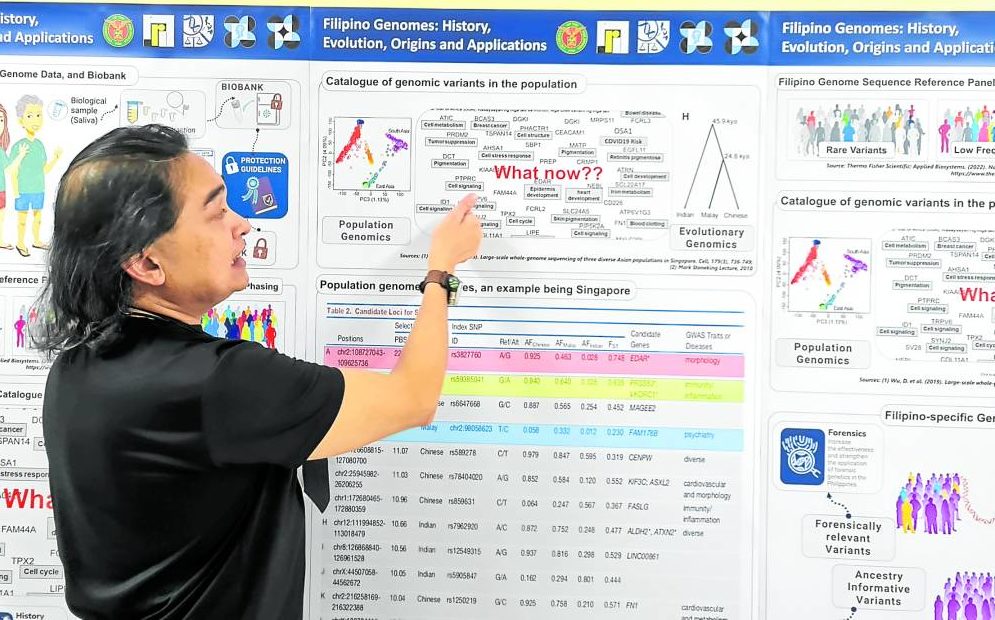

GENE DETECTIVES Frederick Delfin (in black) leads a team of researchers at the University of the Philippines Natural Science Research Institute in attempting to decode the Filipino genome, identifying the genetic markers that determine unique traits across regions and ethnicities in the country. The Filipino Genome Research Program is a three-tiered P172-million project, and Delfin’s team, with Kristin Pusing, Aileen Boquiren and Noriel Esteban, is in charge of the part that focuses on different Philippine demographics. —Photo by Krixia Subingsubing

First of its kind here

Delfin’s team, including researchers Kristin Pusing, Aileen Boquiren and Noriel Esteban, is in charge of the second project under the FGRP that seeks to document the Filipino genome across different demographics—the first program of its kind here.

A relatively obscure field, genomics, or the study of genes, has greatly helped advance global health by diagnosing and treating diseases that burden populations.

While the human genome is mostly the same for all humans, genetic variations—short sequences in the genome that dictate their unique physical traits, among others—in certain demographics can, for example, raise their risk of, or immunity against, some diseases.

At present, much of global pharmaceutical development is anchored on foreign genome research, which means Filipino genes “may not be compatible with new drugs that were developed because we have different genes from the European genome from which it was derived,” Pusing said.

This is why the FGRP is important, according to the UP scientists.

The team expects to finish their work by 2029 but they have already laid the groundwork, including taking saliva samples and other data (like physical traits and genealogy) from volunteers from each of the country’s 17 regions and 24 ethnolinguistic groups, from the Ibaloi of Benguet to the Jama Mapun of Tawi-Tawi.

Finding eligible samples from homogeneous ethnic groups was the easy part since they tend to self-identify and self-organize. Some groups like the Mamanwa of northern Mindanao identify themselves as such only if three of their grandparents from both sides are also Mamanwa.

But it is different in regions where migration and intermarriages may “dilute and obscure” the genetic structure, Boquiren said.

In the port city of Calapan in Oriental Mindoro, the researchers found that many people from one barangay traced their roots across the sea, to Batangas. In Romblon, many families still arrange themselves according to the last letter of their last names, harking back to a Spanish-era edict to standardize Filipino names.

Casualty of war

It was even tougher to find volunteers in Manila, the nation’s cultural hot pot.

From a prospective pool of 45 volunteers, Esteban said only two were eligible for the study. When the team relaxed their conditions—only two native generations instead of three—only 15 more qualified.

Esteban said this could be because of the massive loss of native Manileños during the Battle of Manila toward the end of World War II in 1945—when one in every 10 inhabitants of the capital died.

That amounted to a massive loss of genetic diversity, Delfin said.

“Each of us has up to half a million unique variants. If I am lost, these variants that contribute to the population are also lost,” he said.

It’s hard work overcoming hurdles like these, but if they succeed, the project holds the potential to revolutionize Philippine history, science and anthropology. Because, according to Delfin, “once you have the information of a whole genome, it’s not just ancestry [you can figure out], but you can also look at diseases, medicine, improvement of health, applied forensics.”