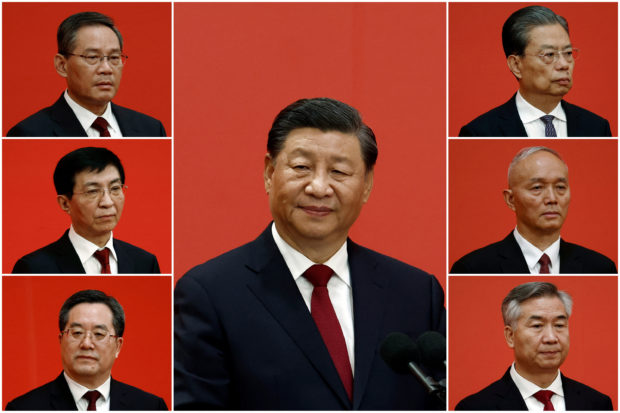

A combination picture shows Chinese leaders Xi Jinping, Li Qiang, Zhao Leji, Wang Huning, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang, and Li Xi meeting the media following the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China October 23, 2022. REUTERS

BEIJING — The Communist Party Congress has laid bare the striking gender imbalance in the upper echelons of Chinese politics, with not a single woman making the 24-person Politburo for the first time in at least a quarter of a century.

As Xi Jinping and his allies concentrated power over the weekend, the party’s highest-ranking woman leader retired.

Veteran politician Sun Chunlan, a vice premier overseeing China’s health policies, was absent from the Central Committee list published Saturday, meaning she has stepped down.

In the world’s biggest political party — which counts 96 million active members — women have never held much power, and now hold even less.

They make up just five percent of the party’s new 205-member Central Committee, while the seven-member Standing Committee — the apex of China’s power — remains an all-male club headed by Xi.

Sun, 72, was the only woman in the former Politburo, the party’s executive decision-making body.

Often dispatched to inspect Chinese cities in the grip of surging Covid-19 outbreaks, the former party chief of Fujian province and Tianjin municipality became the public face of the zero-Covid policy, commanding tough measures wherever she went, prompting the nickname “Iron Lady”.

But figures like Sun are a rarity in Chinese politics, where male patronage networks and ingrained sexism have stymied the careers of promising candidates, experts say.

It is a far cry from Communist Party forefather Mao Zedong’s pledge that “women hold up half the sky”.

“The Chinese Communist Party’s commitment to women’s rights I think is more like a commitment to advance women’s economic rights,” said Minglu Chen, a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney.

“It’s really about: ‘women should join the paid labour force’.”

Chen added that the Communist Party is by nature a masculine and patriarchal institution, from its roots as a social movement to today.

Social conservatism

China is hardly unique in its lack of women in politics.

A prevailing social conservatism and repression of domestic women’s rights activism have made it difficult for women to defy expectations that they will prioritize family life over their careers.

The state has played into these expectations by encouraging women to have babies to offset China’s rapidly aging population. Young women have especially chafed at this, partly due to the lack of policy support for working mothers.

“A lot of women talk about how they cannot juggle the double roles of being a good mother, wife and worker,” said Chen.

She added that most provincial officials selected for promotion have multiple higher education degrees — a prerequisite that disadvantages women.

Many informal patronage networks are also established through frequent socializing at restaurants in heavily male — and often boozy — environments.

“Many of Xi’s former male colleagues in Zhejiang and Fujian are now Politburo members,” said Victor Shih, political science professor at UC San Diego.

“Yet none of his previous female colleagues have made it into the Politburo and not even to top provincial positions.”

China also has low retirement ages for women — 55 for women civil servants compared to 60 for men in the same profession, rising to 60 for women officials at deputy division level and above.

Ministers are expected to retire at 65, while central leaders mostly abide by an informal age cap of 68.

China introduced an informal quota system in 2001, requiring one woman at all levels of government and party except the Politburo. But without a proper supervision mechanism, this was lightly enforced.

“If we had seen a better quota system in place which was reinforced strictly, then we’d start to see different outcomes,” Chen added.

“One-party dominance has led to this as well.”

‘Marginal positions’

The Politburo has only admitted six women since 1948, with only three of them made vice premiers, and no woman has ever made it into the elite Standing Committee.

Observers had hoped Sun would be replaced by Shen Yueyue, head of the All-China Women’s Federation, or Shen Yiqin, who became the third-ever woman provincial party head when she was made chief of Guizhou — but not one woman was promoted.

Even though women make up about 29 percent of the total Communist Party membership, vanishingly few of them manage to ascend from grassroots positions.

For instance, the proportion of women in the Central Committee has hovered at between five and eight percent for the past two decades, according to Shih.

“Discrimination at lower levels prevent them from obtaining high-level positions,” he said.

“Because women held more marginal positions at lower levels, they enter government later than men and they are forced to retire earlier than male counterparts.”

RELATED STORIES

China’s Xi Jinping secures historic third term in office

The power of one: Xi Jinping solidifies grip at party congress