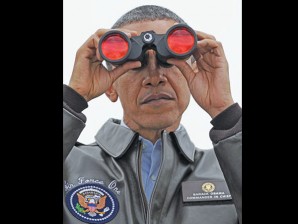

BORDER VISITOR US President Barack Obama peers through binoculars toward North Korea from Observation Post Ouellette during a visit to the Joint Security Area of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) near Panmunjom on the border between North and South Korea. AFP

SEOUL—The security summit that opened on Monday was supposed to be an opportunity for US President Barack Obama and other leaders to find ways to keep nuclear material away from terrorists. So far, North Korea has upstaged that agenda.

And that may be just what Pyongyang intended.

Several heads of state gathered in Seoul for the two-day summit have criticized Pyongyang’s surprise announcement 10 days ago that it plans to blast a satellite into space next month aboard a long-range rocket—a launch Obama views as cover for nuclear missile development.

Obama urged North Korean leaders to abandon their rocket plan or risk jeopardizing their country’s future and thwarting a recent US pledge of food aid in return for nuclear and missile test moratoriums—considered a breakthrough after years of deadlock.

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak’s government warned it might shoot down parts of the rocket if it violated South Korean air space.

Obama and Lee also pressed North Korea’s ally, China, to use its influence to prevent a launch.

Pyongyang’s trick

A Chinese government-backed disarmament expert said allowing the launch to dominate discussions at the summit might be exactly what North Korea wanted.

“I think North Korea did this to overshadow our talks about nuclear security,” said China Arms Control and Disarmament Association head Li Hong. “We shouldn’t fall for their trick.”

North Korea has a history of attention-grabbing moves meant to maximize the impoverished nation’s leverage in talks aimed at trading disarmament pledges for much-needed aid.

The North has previously sparked hopes for a diplomatic solution to a standoff over its nuclear program, before creating a crisis to put itself high on world agendas and then offering to come back to talks, expecting to extract more aid than originally promised, said Ralph Cossa, president of think tank Pacific Forum CSIS.

“If they raise hopes, then dash hopes, then come back again, they think they might get a better deal,” Cossa said. “The better the crisis, the better the deal.”

Iran’s nuclear program

The drama over the North Korean satellite launch has robbed attention from the summit’s moves to lock down the world’s supply of nuclear material by 2014.

It also takes the spotlight away from diplomacy meant to halt Iran’s suspected nuclear weapons program, though Obama stressed he would press the issue of Iran in talks with Russia and China.

“Iran’s leaders must understand that there is no escaping the choice before it. Iran must act with the seriousness and sense of urgency that this moment demands,” Obama said. “Iran must meet its obligations.”

North Korea has said it would launch its rocket around the April 15 celebration of the birthday of North Korean founder Kim Il-sung—and that timing is probably not linked to this week’s nuclear summit, said Koh Yu-hwan, a North Korea professor at Seoul’s Dongguk University.

However, the North may have timed its March 16 launch announcement with the global meeting in mind, he said.

“North Korea can demonstrate to the world how volatile and tense the situation on the Korean peninsula is with the launch,” he said. “That would help it achieve its interests in future negotiations.”

China’s role

China, as North Korea’s biggest source of economic assistance, faces pressure to get the North to halt its rocket plans. However, Beijing maintains its leverage is limited by Pyongyang’s unpredictable nature and overriding concern for stability along its northeastern border.

Chinese President Hu Jintao on Monday met with the South Korean president and later with Obama. Reports from AP and New York Times News Service