Baguio’s wartime role preserved in carving

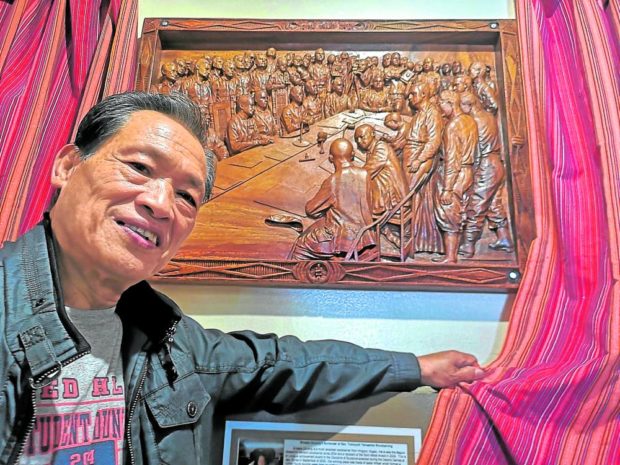

PEACE AT LAST | This wooden relief depicts a historic event on Sept. 3, 1945, when Japanese Imperial Army General Tomoyuki Yamashita signed his surrender papers in the presence of US Maj. Gen. Edmond Leavey at Camp John Hay in Baguio City. Its carver, Ernesto Dul-ang (shown in photo), used to work at the former Camp John Hay Air Base. (Photo by EV ESPIRITU / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

BAGUIO CITY, Benguet, Philippines — A wooden relief featuring Japanese Imperial Army Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita hangs along the stairway of the rehabilitated Baguio Museum here.

Rendered by Ifugao-born artist Ernesto Dul-ang, the carving shows Yamashita, the “Tiger of Malaya,” formally signing his surrender papers on Sept. 3, 1945, at Camp John Hay Air Station where he was taken after he was captured in the Ifugao town of Kiangan by local guerrillas a day earlier.

A painting of the same event hangs above the fireplace of the US Ambassador’s Residence inside Camp John Hay.US Ambassador to the Philippines MaryKay Carlson unveiled the carving when she visited Baguio to attend the Sept. 2 relaunch of the city museum, which was refurbished using a P6.5-million US government grant.

But Dul-ang’s artwork was the highlight of the event, given that Yamashita’s capture on Sept. 2 and official surrender 77 years ago finally ended World War II.

A former Camp John Hay employee, Dul-ang said he was commissioned by the US military to create an earlier version of the Yamashita surrender carving, which was taken to the US.

Article continues after this advertisementThe carved Yamashita piece is even more significant because it was a reminder of Baguio’s place at the beginning and end of the war.

Article continues after this advertisement‘Alpha, Omega’

Baguio was “the Alpha and the Omega” of World War II because the war ended in Baguio four years after Japanese bombers launched the Pacific leg of the second global conflict by attacking that former American base on Dec. 8, 1941, said Reynaldo Mapagu, administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office.

Japanese warplanes attacked Camp John Hay “hours after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii,” Mapagu said when he spoke at the 77th commemoration of the end of World War II on Victory Day here on Sept. 3.

Ending the war was not a Baguio affair alone. Guerrillas resisting Japan’s invasion fought all over northern Luzon and the Cordillera and cornered Yamashita in Kiangan.

Japanese soldiers retreated to the Ifugao mountains as they left Baguio, their headquarters in the last months of the war.

Speaking earlier at the Baguio Museum, National Artist for Film Kidlat Tahimik recalled stories shared by Ifugao elders that ancestral spirits on their mountains might have had a hand in ending the war.

Yamashita made his last stand on Mount Napulauan near the town of Hungduan.

The elders believe the ancestral spirits spoke to Yamashita and made him realize, “‘Hey, why waste another 50,000 lives.’ They think it was that moment of reflection that made him come down (to Kiangan where he was captured),” Kidlat said.

Baguio’s role in the war was first discussed in the city by University of the Philippines history professor Ricardo Jose in April 2015.

Jose said Baguio at the time had been holding bombing drills because the government had been braced for an attack. The mountain city was a tactical military target, being home to Camp John Hay and the Philippine Military Academy (PMA), and being accessible to Benguet province’s mines.

Info from guerrillas

During a September 2015 lecture at PMA, retired general and military historian Restituto Aguilar said Filipino guerrilla intelligence was key to Japan’s defeat, beginning with the 1944 discovery in Cebu of the “Koga” papers written by Japanese Admiral Mineichi Koga, which detailed Japanese military strategies in the Pacific.

The documents revealed that a small Japanese force remained in Luzon, which fell quickly when American and Filipino soldiers advanced from Lingayen, Pangasinan.

“Freedom is never free [because it had been] paved with the blood of our heroes,” said Mapagu during the Saturday event, where he awarded the Philippine Liberation Medal and the WWII Victory Medal to the wives and children of 15 Filipino war veterans.

Among them were First Lt. Federico Mandapat Sr., who spied for the Allied Forces after surviving the Bataan Death March; Second Lt. Gualterio Adalim, who helped liberate northern Negros; Staff Sgt. Dominador Halog; medic Sgt. Pablo Laayon; and Staff Sgt. Leon Aquino.

Also awarded were engineering battalion member Sgt. Cirilo Valmonte; Pfc. Domingo Basallo; Pvts. Emilio Antolin, Emeterio Maranan, Confesor Carpiso, Pio Claver, Dionisio Madayag and Alfredo Paderon; veteran Pedro Arellano; and Pvt. Prudencio Lumbag, who was part of the unit that helped the family of President Sergio Osmeña escape Baguio.