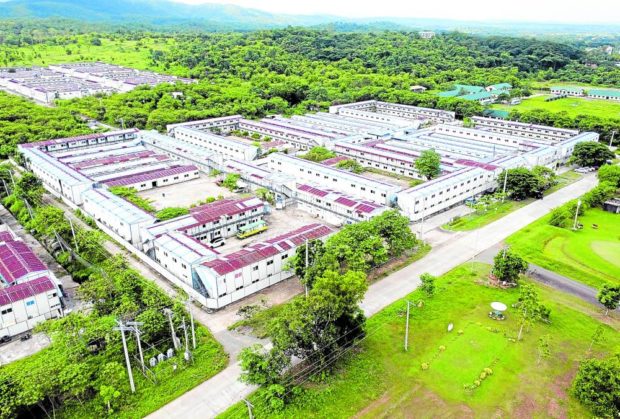

MEGA COMPLEX | Dozens of two-story dormitory-style buildings comprising the Mega Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Center occupy a 10-hectare section of the Fort Magsaysay Army camp in Nueva Ecija province. —PHOTOS BY GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

FORT RAMON MAGSAYSAY, Palayan City, Nueva Ecija, Philippines — Five years ago, Broom was a drug-crazed Pasig City resident who was hauled off by his mother to the Mega Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Center (MDATRC) in Nueva Ecija province, more than 110 kilometers away.

Now 57 and clean, Broom (not his real name) chooses to remain at the sprawling drug rehab center as a volunteer utility worker. There is no motivation for him to return to Pasig as he wants to avoid old friends who had led him to drugs, he said.

“There’s nothing for me outside this facility. I might not find a job, so it’s better for me to stay here,” says Broom, who underwent rehabilitation 18 times prior to being admitted to MDATRC.

He expects to be employed by the center, just like some of his fellow former “residents” who now work there as “house parents.”

Broom abused a variety of narcotics since he was 13, from cough syrup to “shabu” (crystal meth). He is one of about 3,000 “severe cases” who had undergone six to 12 months of treatment and rehabilitation to get rid of their addiction.

Relapses ‘very minimal’

Dr. Nelson Dancel, MDATRC medical chief, says he considers each resident a “success story” who all became “productive members of society.”

“Our cases of relapse are very minimal and have been immediately handled by our after-care division,” Dancel told the Inquirer in an interview.

The center treated, among others, some professionals, including former uniformed personnel, a dentist, and a former village chief from Cabanatuan City, he said.

Of the 244 residents now being cared for by the center, 32 are women and 212 are men ranging in age from 18 to 60.

Each day, the residents come together to share life lessons and display their talents. The rehab activities include group counseling sessions and physical fitness programs, and spiritual pursuits like worships and personal reflections.

The center has a music hall, where residents can play musical instruments, and gym equipment.

Residents also hold online and physical classes for livelihood training provided by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority. Lessons include production of organic fertilizer.

Some of the MDATRC “graduates” who are not from Nueva Ecija have decided to seek employment in the province, according to Dr. Villamin Patricio, chief of the center’s health program.

“There are construction firms that support our program and hire our residents,” Patricio said.

Family needs

The Department of Social Welfare and Development also plays a role. It ensures that the families of people who are admitted to MDATRC are cared for, according to Dancel.

“If a would-be resident is a breadwinner, the local social welfare office must make sure to help the family with their needs,” Dancel said.

The establishment and funding of MDATRC and other drug treatment centers are covered by Executive Order No. 4 as part of former President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs.

Broom and the other residents are lucky to have survived the bloody anti-drug campaign, which by official count left more than 6,000 dead.

Human rights groups say the number could be more than triple that figure and these killings are now being investigated by the International Criminal Court as part of the charges of crimes against humanity against Duterte.

Much room to spare

“The drug menace still exists,” Dancel said in justifying the continued existence of MDATRC.

“We will continue. It’s still necessary,” the retired military medical corps officer said.

Still, MDATRC has yet to maximize its 10,000-bed capacity since it opened in December 2016. The facility was developed in four phases and is the largest of its kind in the country.

It sits on a 10-hectare complex inside the country’s biggest Army camp, courtesy of the Department of National Defense.

Huang Rulun, a philanthropist and Chinese real estate tycoon, donated P1.4 billion to construct the rehab center.

Donations to the center were also made by other Filipino businessmen, including Jorge Consunji of DM Consunji, Kevin Andrew Tan of Megaworld and Francis Cruz of Frey-Fil Corp.

By Dancel’s count, the center’s Phases 1 and 2 accommodated 1,250 residents before the coronavirus pandemic struck in March 2020. The capacity was reduced to 350 beds at the height of the health crisis.

Used for COVID cases

The rehab center also housed up to 4,000 soldiers during its Phase 3 development and took care of 500 COVID-19 patients during Phase 4.

A report by the Department of Health (DOH) in February this year said that it was unrealistic to operate the rehab center at full capacity because it was only one of 30 run by the government around the country. In addition, 43 private drug treatment and rehab centers in the various regions had been accredited by the DOH.

A good measure of the center’s success is the number of its residents who had ended their drug addiction or dependence and starting life anew, according to Dancel.

3,200 recoveries

Almost six years after it opened, MDATRC has helped in the recovery of 3,200 residents following a regimen lasting six months to a year. Around 15 percent of them were women.

Many of them got hooked on drugs either due to peer influence or as a way of dealing with family problems. Some residents have attempted suicide, a tragic testimony to the impact of drugs on some people, Dancel said.

The DOH spends an average of P73 million a year to keep the center running. This money is spent on food, medicine and hospital care, he said.

Its current residents are assisted by 110 medical and support staff—less than the ideal 170-strong workforce needed by the center.

Dancel said the center’s therapeutic approach was modified in 2017 when it adopted a standard introduced by the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Done in several phases, it consisted of orientation, detoxification, early recovery, relapse prevention, predischarge and reintegration into family and community.

He said it was difficult to determine how many have returned to drug use because some local governments do not take an active role in after-care, which takes 18 months.

Dancel realized that stopping the drug menace needed “multiple and complicated” approaches.

“It needs the cooperation of family, sectors, and community. Law enforcement is vital in stopping the supply-demand side of the problem,” he said.

—WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH

RELATED STORIES

COVID-19 hits 200 staff members, patients in Nueva Ecija Mega drug rehab center

WHAT WENT BEFORE: Fort Magsaysay drug rehab center